CLICK ON IMAGES TO ENLARGE. REPEAT IF REQUIRED.

For my last birthday, Shelly and Ron gave me “Eyewitness – 150 years of Photojournalism” by Richard Lacayo and George Russell. Published by Time magazine this covers the history of such photography up to 1995.

The book is a collection of important pictures stitched together by a series of erudite essays from the two writers. I finished reading it today and found it fascinating. Some of the images were familiar to me, but many were not. What I have chosen to feature here is necessarily idiosyncratic, but I hope it will provide a flavour.

I start, as does the book, with ‘the first known photograph of a human being’. Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre exposed this image of Boulevard du Temple, Paris in 1839. Because, in those early days, exposure times were several minutes, any moving thing, such as carriages, horses, or pedestrians would pass on by without leaving a trace. Except for the man standing still for long enough to have his boot polished. Can you spot him?

Some early photographers set out to expose social ills. John Thompson made his picture ‘The Crawlers’ in about 1876-77. ‘Crawlers’ “were poor people so malnourished they would literally crawl to fetch water for the hot tea on which they chiefly subsisted. This woman held a small child all day for its mother, who had found a job in a coffee shop.”

Jacob Riis’s ‘Street Arabs at Night’ in about 1889 slept on “warm spots around the grated vent-holes” in New York’s Lower Manhattan.

Important events could now be recorded. We are told that in 1908 James Hare “had taken a picture that proved the Wright brothers’ plane could fly”. At that time we still believed that the camera could not lie.

However, certainly by 1990, when Paul Higden produced ‘Yalta Conference?’, which included “some latter-day gatecrashers”, we had become disillusioned.

A number of photographers brought back images of combatants in the American Civil War, but it was neither technically possible nor seen to be desirable to photograph the action.

That had to wait until World War 1 when an unidentified photographer produced this painterly picture of ‘British artillerymen feed[ing] an 8-inch howitzer’.

Robert Capa was there with his camera for the ‘Normandy invasion on D-Day’, 6th June, 1944. Unfortunately the is one of only a few images of this event that were saved, most of the others having been destroyed in a dark-room accident.

In 1947 Capa, with David Seymour, Henri Cartier-Bresson, William and Rita Vandivert, and George Rodger formed that prestigious photography group, Magnum.

The Cartier-Bresson picture I have chosen for this piece does not feature in this book. It comes in the form of a postcard sent to me by Giles. The image is of a typically candid shot from this photographer, at the Brasserie Lipp in Paris, taken in 1969.

A later member of Magnum was Don McCullin. In the 1960s and ’70s he “became one of the best- known chroniclers of war and misery”. This picture demonstrates the sensitivity that this man exemplified.

I have selected two images by Alfred Eisenstaedt which book-end WW2. It is amazing that he managed to walk away unscathed when he photographed Joseph Goebbels at a League of Nations Assembly in Geneva in 1933. A year or two later it would surely have been a different story.

I’d rather witness the hate of Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda than the devastation of this ‘Mother and child at Hiroshima’ that Eisenstaedt portrayed in 1945.

Dorothea Lange’s ‘Migrant mother’ from a California migrant workers’ camp in March 1936 “is one of the best-known icons of the Dust Bowl era”.

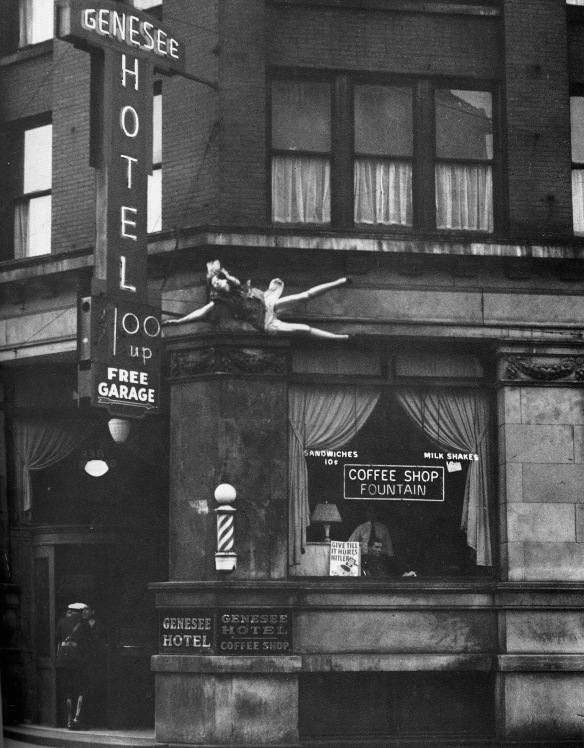

Finally, who, old enough, could examine Russell Sorgi’s 1942 ‘Suicide’, without being transported back to 9/11?

This evening we finished our Chinese takeaway meal.