CLICK ON IMAGES YOU WISH TO ENLARGE. REPEAT IF NECESSARY. DISAPPOINTINGLY THIS DOESN’T WORK FOR THE COLOUR PLATES WHICH BECOME TOO PIXELLATED.

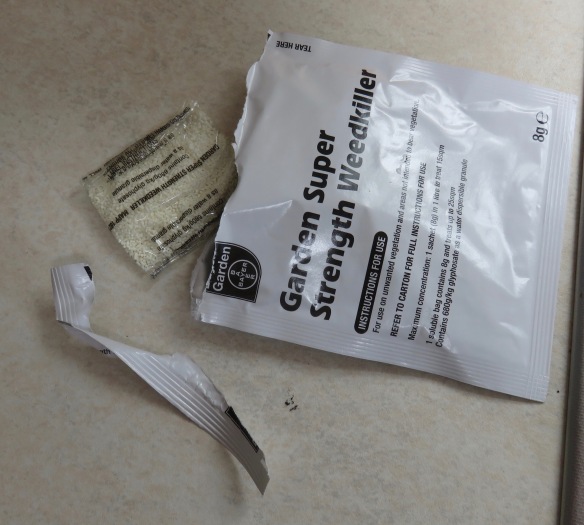

I failed an intelligence test this morning.

Well, in fairness no-one told me that the weedkiller sachets contained further such items. You see, it was my task to zap the weeds in the cracks between the concrete sections of the front drive, and its accompanying gravel path.

So. I merrily tore of the top of the outer covering and tipped the contents into 5 litres of water. I would have immediately added four more inner sachets. But I noticed a transparent packet bearing floating minuscule sections of what looked like vermicelli, and strove to extract this. Ah. It was soluble. So I got the poison all over my fingers and had to wash it off. Of course, the mini-pasta also dissolved, as it was meant to do.

Well, now I know.

Our first iris foetidissima bloomed today. Its days are numbered because The Head Gardener is less partial to them than I am. It must be something in the name.

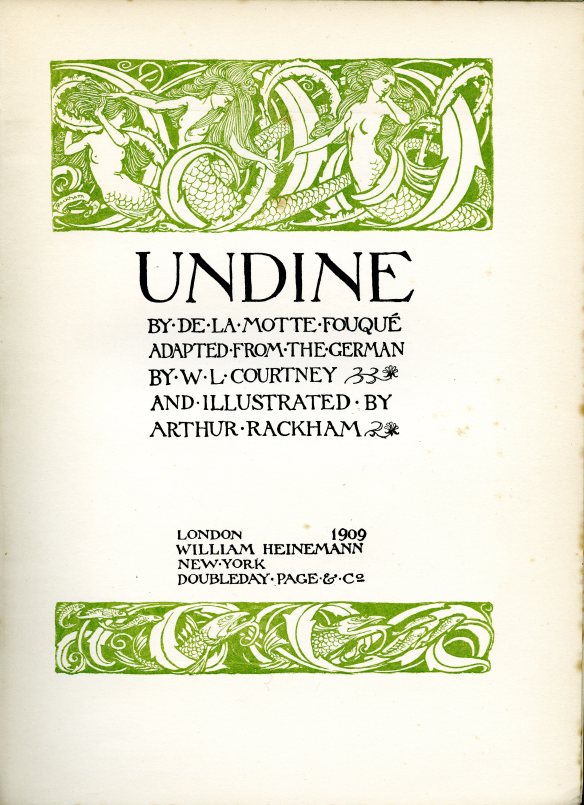

This afternoon I finished reading:

This volume has adorned my bookshelves for 34 years, but, although I have often perused the pictures, I only began to read it a few days ago.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica has this to say about the author:

‘Friedrich Heinrich Karl de la Motte, Baron Fouqué, (born February 12, 1777, Brandenburg—died January 23, 1843, Berlin) German novelist and playwright remembered chiefly as the author of the popular fairy tale Undine (1811).

Fouqué was a descendant of French aristocrats, an eager reader of English and Scandinavian literature and Greek and Norse myths, and a military officer. He became a serious writer after he met scholar and critic August Wilhelm Schlegel. In his writings Fouqué expressed heroic ideals of chivalry designed to arouse a sense of German tradition and national character in his contemporaries during the Napoleonic era.

A prolific writer, Fouqué gathered much of his material from Scandinavian sagas and myths. His dramatic trilogy, Der Held des Nordens (1808–10; “Hero of the North”), is the first modern dramatic treatment of the Nibelung story and a precedent for the later dramas of Friedrich Hebbel and the operas of Richard Wagner.’

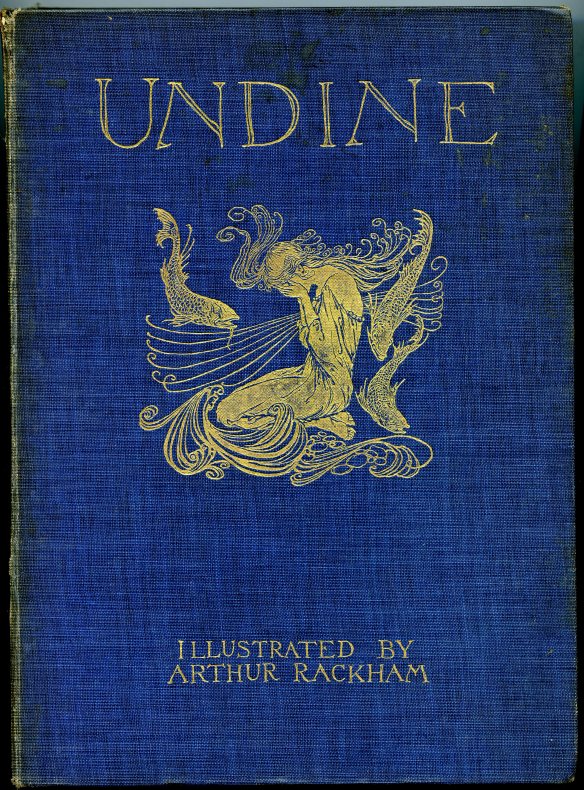

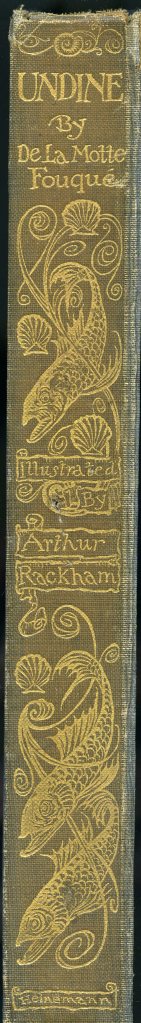

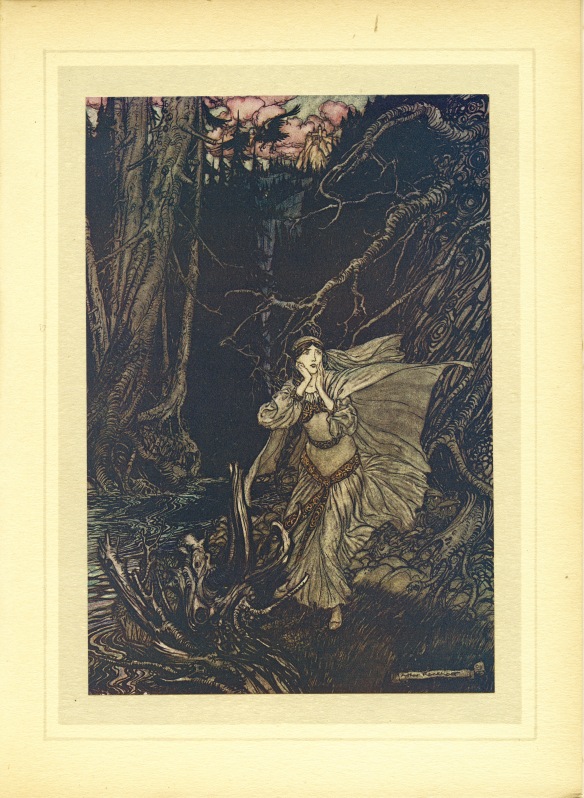

It is a measure of the prowess of the artist, the foremost English book illustrator of the early twentieth century, Arthur Rackham,

that it is his name that appears on the front cover,

although the writer features on the spine.

One reason I never pursued book illustration as a career was that I knew I had no hope of ever matching this master.

There are 15 colour plates in my Heinemann edition. I forced myself to make a limited selection, and chose these two examples of the many moods Rackham is capable of evoking. He is noted for his trees.

Each chapter is topped and tailed by an exquisite little vignette, pertinent to the story.

Let us not forget the translator, W. L. Courtney, who has produced a beautifully poetic rendering of the original romantic fable of 1811. I do not know how far from the original he has strayed, but suitably quaint archaic language speaks of the bygone days of knights, honour, chivalry, water sprites, and magic. The poetic prose is especially descriptive. It was fun to read, even without Mr. Rackham’s input.

This evening we dined on chicken marinaded overnight in lemon and piri-piri sauce, carrots, runner beans, ratatouille, and mashed potato and swede, followed by lemon tart and cream. The Cook drank Hoegaarden and I drank la Croix des Celestins Fleurie 2014.