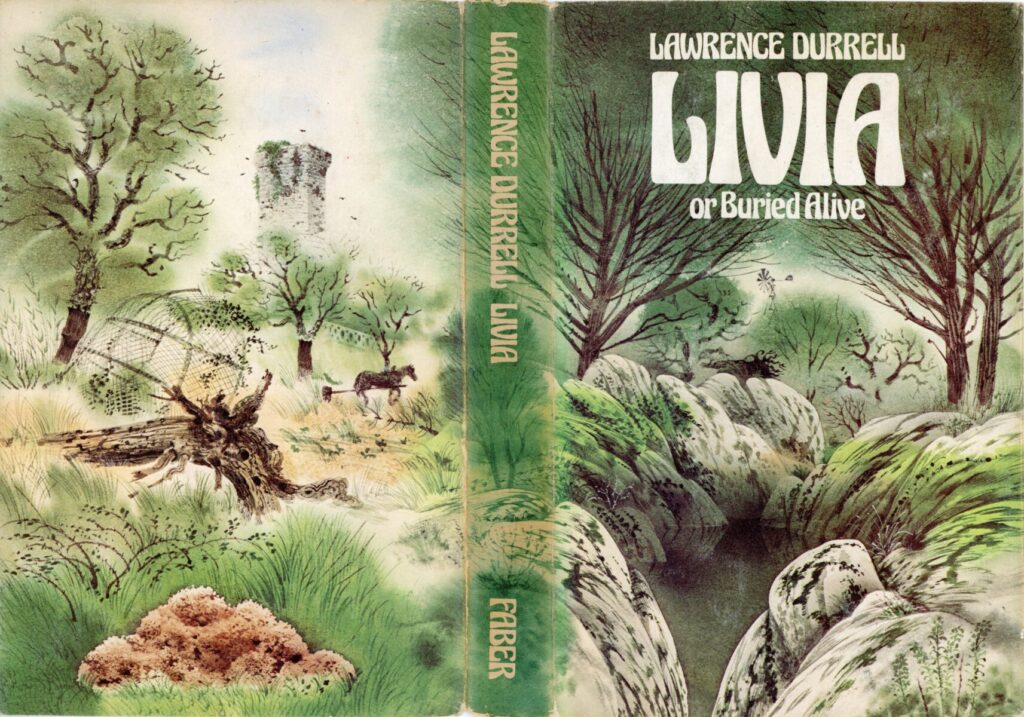

As we enter the second week of August the skies throughout the day have been overcast; the temperature over cold; the breeze underwhelming; so I donned a jacket, remained inside, and spent the day finishing my reading of the final volume of Lawrence Durrell’s Avignon Quintet,

the book jacket of which is illustrated by David Gentleman.

As the characters from the five works gather for the last time the narrator, Blanford, considers that he is now in a position to write the book that they have been helping him put together. These volumes are of course it.

We are now experiencing the aftermath of the Second World War with its reprisals, its War Crimes trials, and the beginnings of the consequential population readjustments and migrations.

Themes of sexuality, love, lust, and the nature and power of orgasm continue; triangular relationships, incest, and orientation are underlying – this is managed with non-pornographic eroticism. The search for the mythical treasure of the Templars remains a thread which seems about to be snapped.

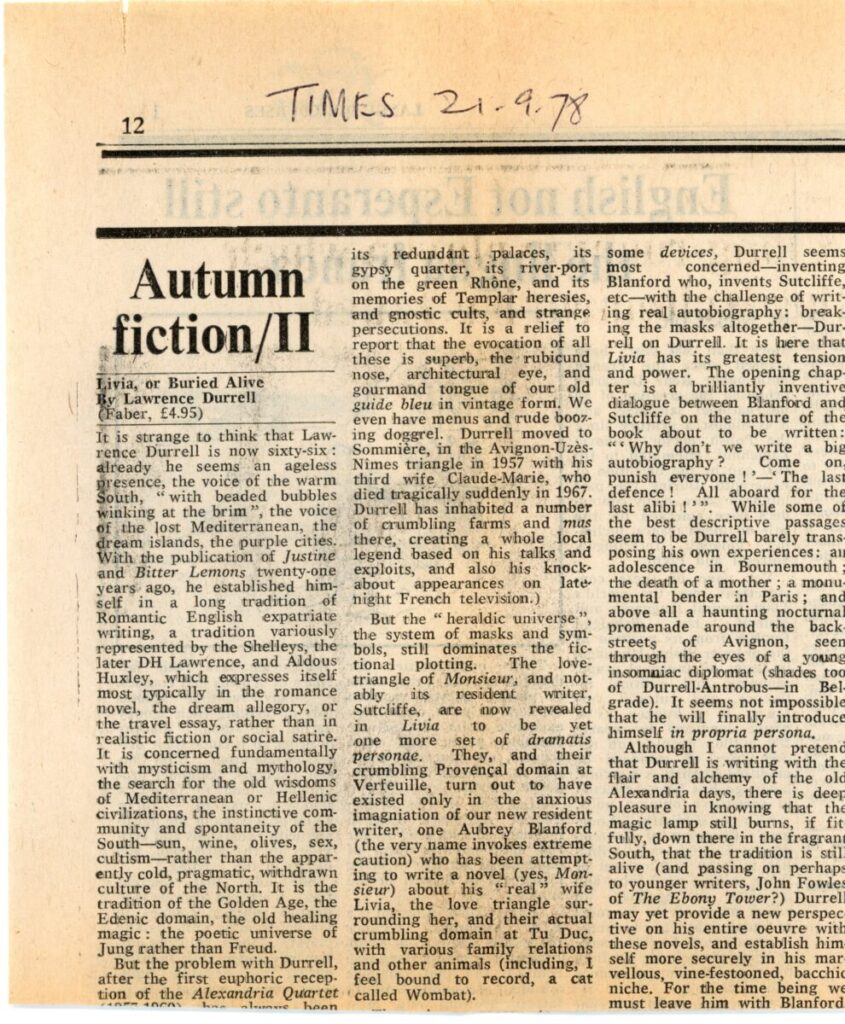

Whilst I would agree with the blurb-writer’s observation of Durrell’s magical descriptive writing, I think the best of this is contained in the earlier chapter concerning the converging of the European gypsy tribes where, long before the writer used the phrase “human tide”, his fluent prose described just that ebb and flow, managing the varying lengths of his superb sentences to evoke the essence of the gathering stream.

Particularly in the first chapter and the notebook section, the author enjoys amusing wordplay like puns (in either English or French) and misquotations, all of which exemplify his apparent ease with language.

This evening we all dined on further helpings of yesterday’s Monday pie with fresh vegetables and the same beverages, followed by Berry Strudel