There was not much sun breaking through the clouds today.

This is quite useful when photographing white flowers like clematis Marie Boisselot as I did on my way to open the back gate for Aaron.

Geranium Palmatums and their attendant red fuchsias caught a touch of it as I walked along the Shady Path.

Bees were out early. This one still visited the ageing Festive Jewel in the Rose Garden into which I had been enticed by the magical scents that permeated the air.

A spider preferred to walk on the Blue Moon.

White beauties enjoying their time out of the limelight included Margaret Merril and Madame Alfred Carriere, sharing the entrance arch with Summer Wine.

Special Anniversary, Zéphirini Drouin, Absolutely Fabulous, and Mum in a Million all contributed their intriguing essences to the perfumed blend.

Despite its name the Sicilian Honey Garlic makes no apparent contribution to the mix.

Oriental poppies; libertia welcoming visiting bees; yellow irises; and red peonies enliven the borders of the Back Drive.

From a gentle amble through the garden I turn to the terrifying Moscow Show trials of the 1930s.

According to Wikipedia ‘The Moscow Trials were a series of show trials held in the Soviet Union at the instigation of Joseph Stalin between 1936 and 1938 against so-called Trotskyists and members of Right Opposition of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. There were three Moscow Trials: the Case of the Trotskyite-Zinovievite Terrorist Center (Zinoviev–Kamenev Trial, aka “Trial of the Sixteen,” 1936), the Case of the Anti-Soviet Trotskyist Center (Pyatakov–Radek Trial, 1937), and the Case of the Anti-Soviet “Bloc of Rights and Trotskyites” (Bukharin–Rykov Trial, aka “Trial of the Twenty-One,” 1938).

The defendants of these were Old Bolshevik party leaders and top officials of the Soviet secret police. Most defendants were charged under Article 58 of the RSFSR Penal Code with conspiring with the western powers to assassinate Stalin and other Soviet leaders, dismember the Soviet Union, and restore capitalism.

The Moscow Trials led to the execution of many of the defendants. They are generally seen as part of Stalin’s Great Purge, an attempt to rid the party of current or prior oppositionists, especially but not exclusively Trotskyists, and any leading Bolshevik cadre from the time of the Russian Revolution or earlier, who might even potentially become a figurehead for the growing discontent in the Soviet populace resulting from Stalin’s mismanagement of the economy.[citation needed] Stalin’s hasty industrialisation during the period of the First Five Year Plan and the brutality of the forced collectivisation of agriculture had led to an acute economic and political crisis in 1928-33, a part of the global problem known as the Great Depression, and to enormous suffering on the part of the Soviet workers and peasants. Stalin was acutely conscious of this fact and took steps to prevent it taking the form of an opposition inside the Communist Party of the Soviet Union to his increasingly autocratic rule.[1]‘

Several of the victims of these judicial farces were personally known to Arthur Koestler, the Hungarian born British novelist who penned ‘Darkness at Noon’ in their memory decades before Mikhail Gorbatchev, in the late 1980s, introduced Glasnost, thus beginning the democratisation of the Soviet Union.

I finished reading this important book for the second time today. Without naming either Stalin or the USSR the work describes the energy-sapping destruction of the will of previous leaders who were now out of favour and forced by torture to contribute to their own finding of guilt and subsequent execution. Koestler’s prose is simply elegant but he describes an atmosphere of destructive, erosive, terror in an incongruously readable manner. I don’t often knowingly read a book twice, but since Louis had been reading his copy on his recent stay with us, I was prompted to do so.

Daphne Hardy’s translation renders the book most accessible, and Vladimir Bukovsky’s introduction is eloquently informative.

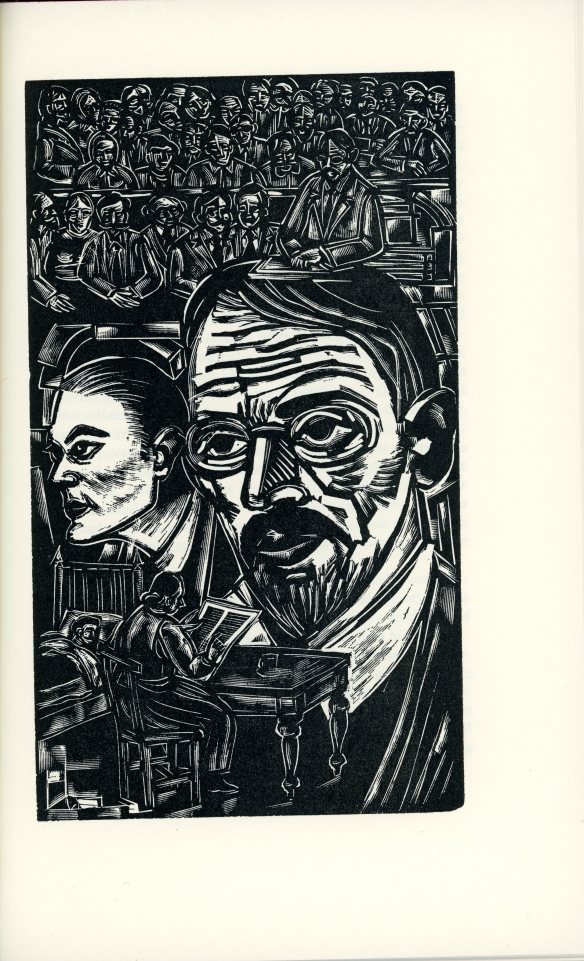

George Buday’s belligerent, brooding, wood engravings brilliantly supplement the attritional ambience of Koestler’s work.

The boards are blocked with a suitably spare design by Sue Bradbury.

We are now driving over to Emsworth for a curry outing with Becky and Ian. I will report on that tomorrow.