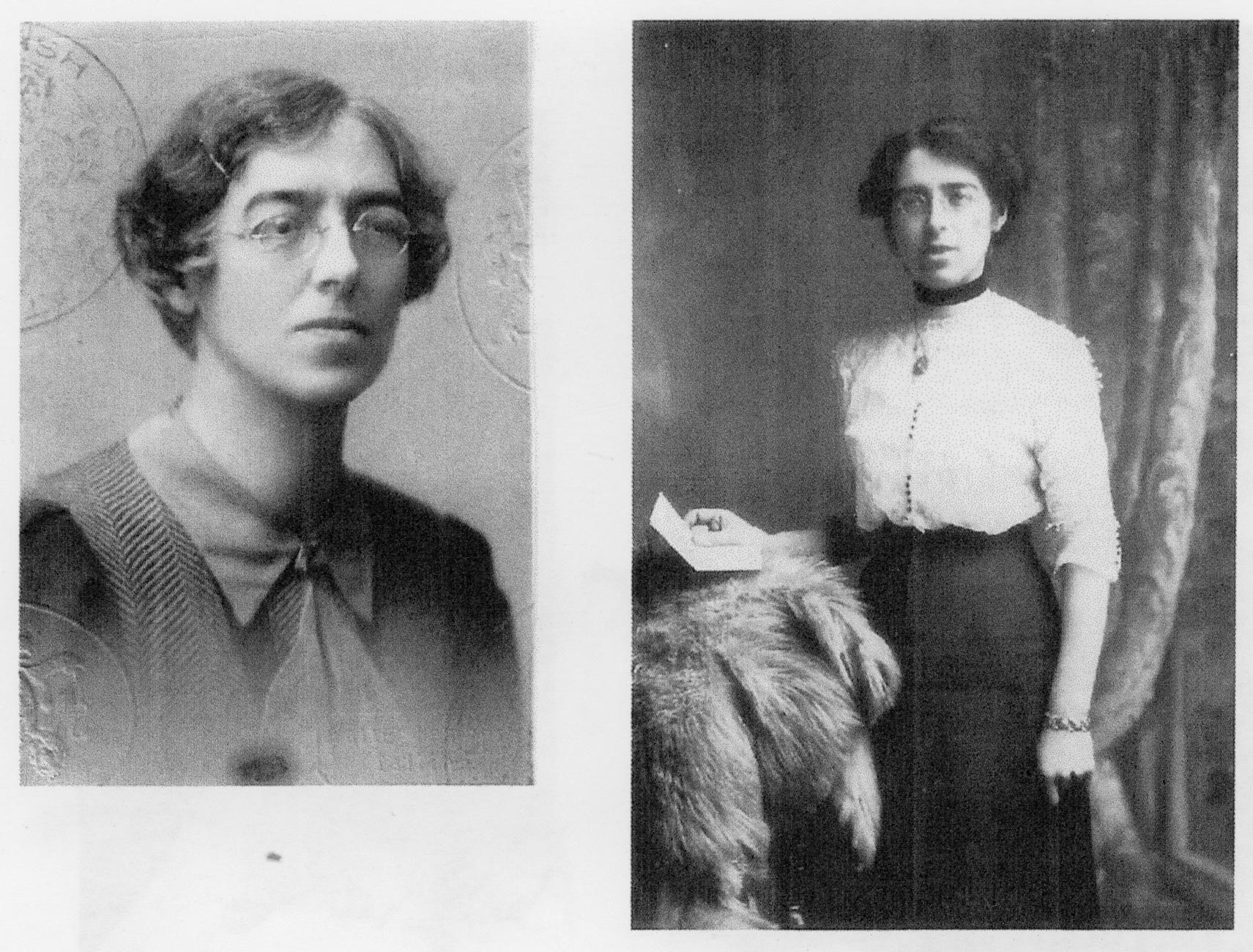

Then came the Russian revolution, when it was not safe to be out in St Petersburg at night, and even at dusk. The only police were very inefficient student volunteers who nevertheless did their best. All the old police were killed during the first days of the Revolution. As my great aunt Mabel was out every day she witnessed a great deal of the excitement. She saw police being dragged out of the Police Station, but did not go near enough to discover whether they were dead or alive. She saw gun battles through the windows of the building between soldiers and police. Two or three times she narrowly escaped being shot at herself.

Mabel speaks of the severe lack of food and its consequent rationing from the middle of the second decade of the 20th century:

“…. about 1916, one could no longer go into shop and buy bread, for it was rationed. It gradually got worse and worse after the Revolution. One had to wait for hours in a queue for a small piece of bread.

Then all cereals disappeared until, in 1917, one could buy nothing but meat at a very high price, fish, and vegetables; and in the middle of winter there were no potatoes.

The ration of bread dwindled down to 2 ounces, or even one ounce, per person. In the summer of 1918, I did not get any at all; what one did get was half straw and sand. The only chance one had at that time of getting any bread was from the speculators – secretly sold by them, and a 10 lb loaf would cost 130 roubles – that would be £3 at the then rate of exchange. The loaf contained sand, and one could feel the grit in one’s teeth. But I was glad to get it and thought it delightful compared with the rationed bread. Of course, these speculators were caught and sometimes imprisoned.

One could sometimes get dried vegetables, consisting chiefly of cabbage. One of my pupils brought me some horse’s oats which he had got hold of, and he suggested mixing them with dried cabbage to make a kind of rissole. To do this one had to separate the husks from the grain, so I put them through a coffee grinder and then through a sieve; a lengthy process as you can imagine. But they really made quite a palatable rissole.”

She continues:

“My sister and I used to spend hours hunting for food in the market places. A friend of mine would say “Do you know you can get rice in such or such a place?” – Off we would go at the first opportunity, only to find that the Bolshevik police had confiscated it after raiding the market and taking off all the food.

Occasionally I was lucky and came home triumphant with a little sago or half a pound of bread.

We also had great difficulty in getting milk. A man would be selling milk, and I would wait in a queue for an hour at the St Nicolas station. Then came the Bolshevik police, and the milk seller would fly with the queue running after him. It was so funny! I can see them now running shelter-skelter over the rails behind a railway truck. Every vigil there were raids in the houses. The people in different houses kept guard all night in turns.”

Mabel further tells us:

“Hardly a night passed without hearing shots and people shouting and running. After a while I got accustomed to it so that it did not wake me.

At night the soldiers would raid the grocers’ shops and get out the wine. One day outside my house I saw a stream of wine running down the gutters. The soldiers had been ordered to get rid of all the wine they could find, and they were pumping it out of the cellars.

Clothing got to such a price that people were often stopped in the street and forced to take off their clothes, boots, and other articles, going home almost naked. A girl of 18 years was made to take off all except her chemise. “now go home, dear, or you will catch cold, they said. She was a friend of one of my pupils.”

Of raids on private homes our diarist records:

“At one of the houses where I taught, nine or ten soldiers came to raid the house, and the Hall Porter tried to prevent them from entering, and in doing so his little girl of eight years, who was in bed, was killed by a bullet fired by one of the soldiers at the Hall Porter.

One of my best Russian friends had her flat raided; nine Russian soldiers came at 2 o’clock in the morning and demanded entrance. They seized every scrap of food they could find and then arrested the husband for no reason beyond that he was friendly with the English. I often telephoned to his wife to know whether he was going to be released. One day she was in a terrible state as her husband was to be shot. She did everything she could to try and save him. At last she was advised to go to one of the Bolsheviks; by paying a terrific sum of money he was let off. He then escaped to Estonia, and now he is living in London.

The summer of 1918, I was living in the country not far from Petrograd. Every night I was sure that the soldiers would come to raid the house where I was staying ………. later I stayed for 10 days with some people, and there the Bolsheviks came to commandeer. Six soldiers walked in with hats on and cigarettes in their mouths; they came three times and the third time was 9 p.m. They asked us to move out the same evening.

By now the British Ambassador was leaving Petersburg and the English colony was under the care of the British Consul, Mr Woodhouse. This man started to organise a party of those who were wishing to go home to England. We were about 25 in all. I had been so horrified to see how terribly thin and emaciated my sister hd become through months of semi-starvation, that I decided at once that we must join the party for England.”