On this, another day of rest and recuperation while recovering from a heavy cold, I finished reading

which, according to Studs Terkel in his excellent introduction, “Dorothy Parker, at the time of its publication in 1939, called ‘the greatest American novel I have ever read’ “. Like Terkel, who has surely read many more, I would concur.

The Folio Society produced this fine edition to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the original publication. Without giving away too much of the story I can say that this is the tale of myriads of farming families driven from their rented lands by the Dust Bowl drought and the owners of their farms which could no longer provide their living. Terkel cites the 1988 drought as a repetition of the earlier natural disaster. And here we are again facing the consequences of worldwide similar events.

Firstly, this is a gripping tale focussed on the flight of one family and those they encounter along the way to the promised land of California. The prose is of the quality that was to win the author the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962. The narrative flows along with intermittent lyrical notes. Speech is given in the vernacular which is natural and uncomplicated.

Steinbeck uses straightforward language to describe landscape, events, atmosphere, and character to a degree that takes us right there with him. We see, hear, touch, and taste, with all the protagonists; and empathise with their feelings.

We are reminded how shared adversity can both bring people together and divide them; we see generosity in that adversity and we see how fear of difference can turn to hate and violence.

The division and mistrust between the haves and have-nots reflects today’s chasms. If you have not yet read this novel I would urge you to do so. There are many lessons therein for all of us.

Terkel was an inspired choice of introducer because his prose is commensurate with that of Steinbeck. He places the work in history and in the writer’s oeuvre.

Bonnie Christensen’s muscular illustrations are, as can be seen by the pages in which they are set (except for the full page one), faithful to the text:

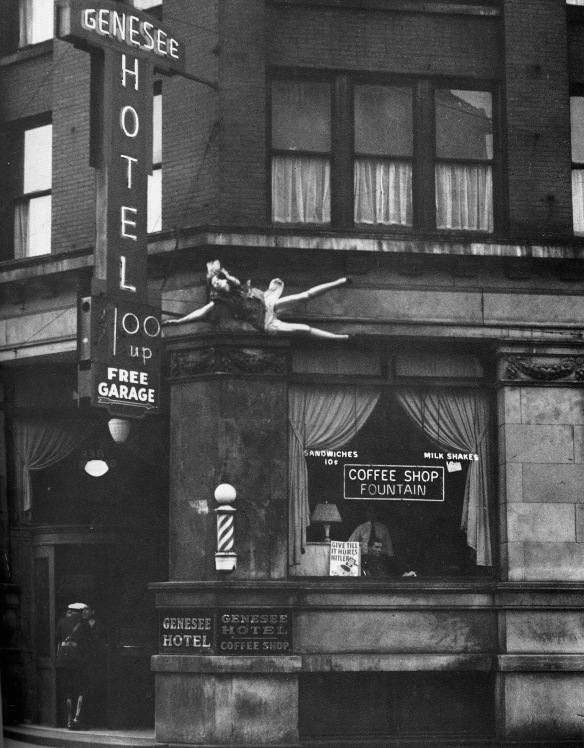

The diagonals crossing the front cover continue across the spine to the back board. The design is based on the artist’s frontispiece above.

My header picture is Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, from a California migrant workers’ camp in 1936.

This evening I dined on more of the chilli con carne while the others, except for Ellie, enjoyed beef burgers and chips. Jackie drank Hoegaarden and I drank more of the Gran Selone.