Yesterday evening, after dinner, Jackie attempted to turn off the extractor fan. She pulled the cord. Something snapped inside. To reach it I had to climb up on a chair. Fortunately the glass spice jar I knocked off the top of a tower of shelves didn’t break. I fiddled around and found a screw under a cap. I unscrewed it and removed the casing, to discover a small piece of plastic had sheered and come adrift. This meant I had to release the mechanism manually. At least I stopped the fan, but until we buy and fit another, that is how it will need to be turned on.

This morning, Joe, The Lady Plumber’s ‘lad’ came to remove the now redundant piping from our bathroom. Before that we had bought the fireworks for Saturday from Lidl, posted the redundant TV box to BT, and took in two jackets for cleaning.

I then cleared ten brick lengths of bramble and ivy roots from the back drive.

Jackie was out to lunch with her sisters, but sensible enough to have left me a beef and mustard sandwich  garnished with tomatoes. Whilst I enjoyed it I also got pleasure from the cluster of sunlit pale blue morning glories shot with pastel pink that can be seen through the kitchen window.

garnished with tomatoes. Whilst I enjoyed it I also got pleasure from the cluster of sunlit pale blue morning glories shot with pastel pink that can be seen through the kitchen window.

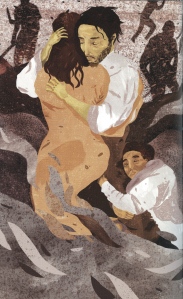

This afternoon I finished reading Mario Vargas Llosa’s haunting historical novel: ‘The War of The End of The World’. A Peruvian, the author chose to set his book in Bahia, a North-Eastern state of Brazil, as the nineteenth century was coming to a close. The book was originally published in 1981. My 2012 Folio Society edition uses the 1984 translation by Helen R. Lane. Ben Cain’s illustrations reflect the primitive nature of the story.

This afternoon I finished reading Mario Vargas Llosa’s haunting historical novel: ‘The War of The End of The World’. A Peruvian, the author chose to set his book in Bahia, a North-Eastern state of Brazil, as the nineteenth century was coming to a close. The book was originally published in 1981. My 2012 Folio Society edition uses the 1984 translation by Helen R. Lane. Ben Cain’s illustrations reflect the primitive nature of the story.

A very lengthy tome, it was only the political sections that I had difficulty following, and sometimes found rather boring. We are sensitively shown how the extreme poverty of underprivileged, landless, disabled, and uneducated people of that time and place affected their wretched lives, enough for them to flock to the shelter of a community established by a mystic preacher. Each character is beautifully and touchingly described as the civil War of Canudos progresses to its bitter end. The harshness of the terrain and climate adds to the horrors of thirst, starvation, wounding and destruction, which beset both the settlers and the soldiers sent to drive them out. Transcending all this is the superhuman emotional and physical strength displayed by people ultimately barely alive. The prose, having set the scene at a more leisurely pace, builds naturally, briskly, to a final crescendo. I have to say I was confused by the alternation between present and past in various sections. This was clearly not the fault of the translator, who seems to have done a remarkable job.

Ultimately the state cannot tolerate this enclave hoping to live in peace apart. The title of the book reflects the belief that the world would end at the turn of the next millennium, a myth which perhaps Vargas Llosa is dispelling.

Not knowing much about South American history, this novel had me researching the conflict that took place during 1896 and ’97. I learned that Antônio Vicente Mendes Maciel, an itinerant preacher who had been wandering the less inhabited areas of Brazil for the previous twenty years and had taken the name Antonio Conselheiro (The Counsellor), set up the  community in question in 1893. Bahia was then a desperately poor zone, with a disenfranchised population living on subsistence agriculture. As such it was ripe for his influence, seeking hope from his promise of a better world. After a number of unsuccessful attempts at military suppression, a large Brazilian army force overran the village and killed nearly all the inhabitants.

community in question in 1893. Bahia was then a desperately poor zone, with a disenfranchised population living on subsistence agriculture. As such it was ripe for his influence, seeking hope from his promise of a better world. After a number of unsuccessful attempts at military suppression, a large Brazilian army force overran the village and killed nearly all the inhabitants.

Daniel’s fish and chip restaurant provided our dinner this evening. My beverage was tea; Jackie’s was coffee.

The War Of Canudos

One comment