This morning I finished reading

In this truly great example of an English novel rivalling the realism of the French Balzac or Zola, Bennet has traced the disparate lives of two sisters born of the same provincial family, delineating their different characters and chosen paths, and reuniting them in their later lives. A sentence from the very last chapter could serve as a statement about the story as a whole: “she paused in wonder at the contrasting hazards of existence.”

The work was first published by Chapman and Hall in 1908, although the author’s chosen period was half a century earlier, as indicated by such as a test ride of the unsteady and uncomfortable aptly termed “bone-shaker” bicycle.

One of the sisters, the more traditionally restrained and less adventurous, never moves from her place of birth; the other, unpredictable, wilful and risk-taking leaves her homeland for a life abroad.

The author has a deep, insightful, knowledge of human nature and the skill of describing and exploring the thoughts, minds, and actions of his characters, both male and female.

Bennet has genuine sympathy with his protagonists, sensitively understanding their strengths and their flaws. He manages their negotiations with each other, – knowing when to enter into subtle persuasion or direct confrontation and when to accept an adamant stance. He shows the potential folly of either headstrong or too reticent love; the importance of trust, and the danger of deception.

“Constance, who bore Mrs Baines’s bunch of keys at her girdle, a solemn trust, moved a little fearfully to a corner cupboard which was hung in the angle to the right of the projecting fireplace, over a shelf on which stood a large copper tea-urn. That corner cupboard, of oak inlaid with maple and ebony in a simple border pattern, was typical of the room. It was of piece with the deep green ‘flock’ wallpaper, and the tea-urn, and the rocking-chairs with their antimacassars, and the harmonium in rosewood with a Chinese papier-mâché tea-caddy on the top of it; even with the carpet, certainly the most curious parlour carpet that ever was, being made of lengths of stair-carpet sewn together side by side. That corner cupboard was already old in service; it had held the medicines of generations. It gleamed darkly with the grave and genuine polish which comes from ancient use alone. The key which Constance chose from her bunch was like the cupboard, smooth and shining with years; it fitted and turned very easily, yet with a firm snap……..” demonstrates Bennet’s facility for description of place and person. Just as the room gives a flavour of the residents, there are many passages where physical images render their characters. Readers will note that plentiful alliteration eases the flow of the prose. Many further examples include those making use of the siblings’ names, e.g. “Sophia slipped out of bed”, “Constance eagerly consented”; “the tap in the coal-cellar out of repair could be heard distinctly and systematically dripping water into a jar on the drop-stone” emphasising a moment of tension; “the enervating voluptuousness of grief” being such an apt description.

Similes like “the topic which secretly ravaged the supper-world as a subterranean fire ravages a mine” abound; “During eight years the moth Charles had flitted round her brilliance and was now singed past escape” is an example of a rich metaphor.

Dry humour, such as the chapters on a troubling tooth removal, is in plentiful supply.

Tim Heald’s introduction gives useful information about Bennet and his time.

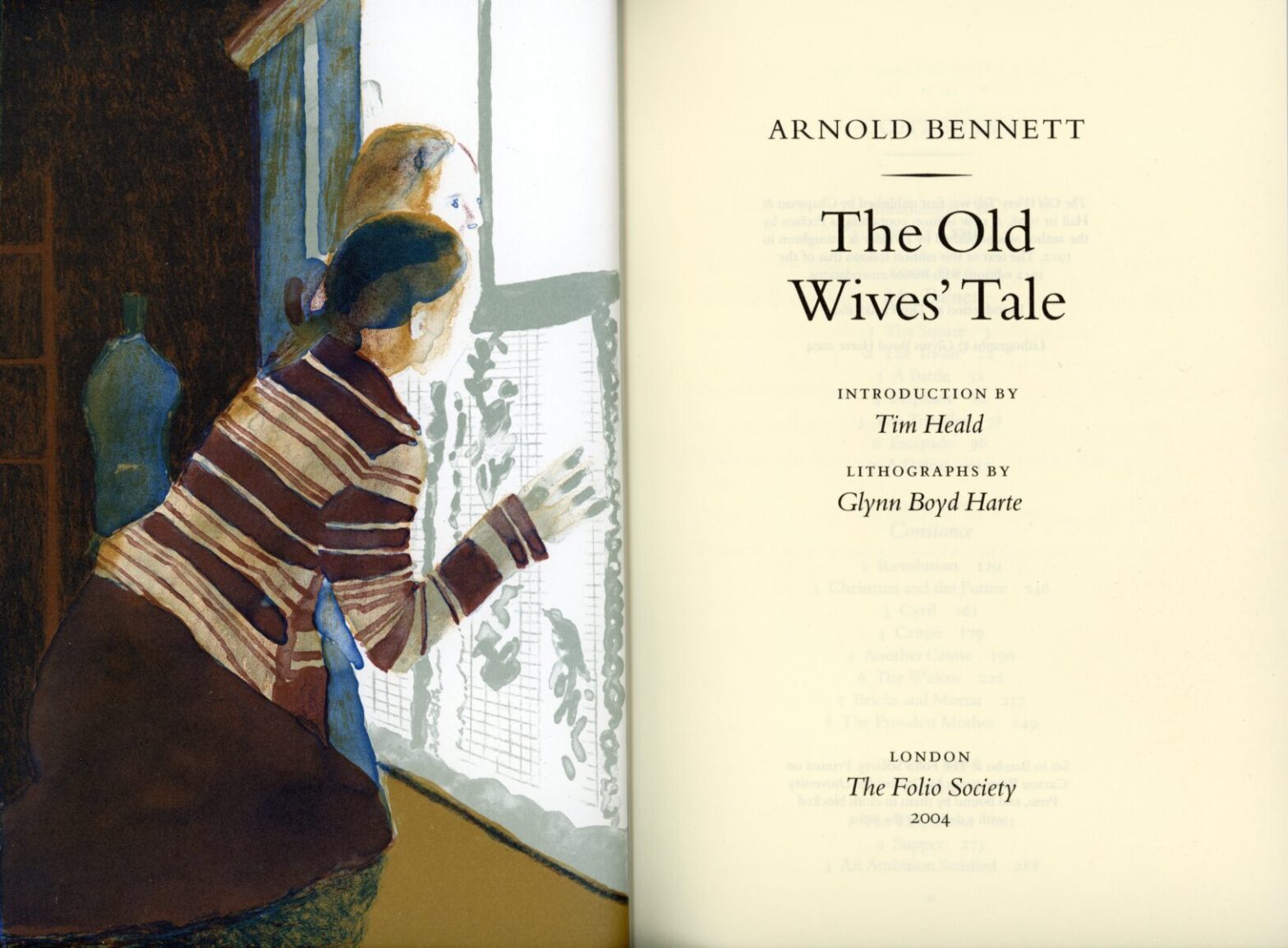

The header picture shows the title page and frontispiece, which is to my mind the more fitting lithograph by Glynn Boyd Harte.

Whilst the composition of Harte’s illustrations is impeccable the figures are ill defined and faces seem to be avoided, when I can’t see any justification for this in the author’s meticulous work. It is hard to see the beauty described by Bennet in the couple greeting each other in the second image, and one would never know the distressing disaster being discussed in the last one.

This evening we dined on succulent roast lamb, mint sauce, boiled baby new potatoes, firm carrots and broccoli, with tender cabbage and tasty gravy.

Thank you for this excellent review!

Thank you very much, Anne

Another excellent review and meal, Derrick. You poor poor man. ????

Thank you so much Pat

I like the illustration, I don’t mind the lack of definition.

Thank you very much, Sylvie

Another excellent review, Derrick. I can’t decide if I like the illustrations or not. I love the colors and composition. Perhaps it’s the lithograph. They seem designed to be seen at a distance. The faces all seem to be wearing masks.

Best wishes for tomorrow.

Thank you so much, Merril

Interesting critique of the illustrations. They remind me of illustrations in children’s books.

Thank you very much, Liz

You’re welcome, Derrick.

I enjoyed this wonderful review, Derrick!

Hmm…those illustrations are interesting and different. Those faces don’t convey much, if anything.

(((HUGS)))

Thank you very much, Carolyn XX

You make it seem a great fireside read, so is on my (long) list.

Perhaps the illustrations are an attempt to let the reader impress their perceived visage rather than present one? Or is it masques and mystery at play here?

Thank you very much, Queen Hephzibah

Thank you for this review. The novel sounds delightful and interesting. I’m glad the sisters are reunited in their later lives as is often the case. May your hazards of existence be non-existent or at least few and far between.

Thank you so much, JoAnna

I like the illustrations, it’s almost as though the reader is allowed to keep their own idea of the facial features of these characters.

Derrick, I have recently read several reviews of this from other bloggers which led me to acquiring the book. Your review encourages me to make a start. I just need the time!

I agree, the illustrations are a bit blank in expression.

I enjoyed your excellent review, Derrick. Thank you! I too am glad the sisters reunited later in life.

An extraordinary review, Derrick. Perhaps the blank faces are to spark the reader’s imagination.

That could be so, Eugi. Thank you very much

You’re welcome, Derrick.

I wish more contemporary fiction could take the time for such verdant descriptions. Sadly minimalism (or nihilism) seems to be having its day.

Thank you very much, Elizabeth

Yet another author I know only by name. So little time, so many books.

Thank you very much, Quercus

Another fine review, Derrick. I’ve started reading Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde based on one of your earlier reviews. Thank you.

Much appreciated, Alys

Interesting style of illustration

Thank you very much, Sheree

Been thinking of you yesterday and today (Tuesday). Sending prayers and best wishes your way.

(((HUGS)))

I meant Tuesday and today (Wednesday)!

Thank you very much, Carolyn XX

Thank you very much, Carolyn XX

Excellent review, those illustrations are really good

Thank you very much, Gary

Everything OK, Derrick? How are you and Jackie?

Thank you very much, Lavinia. All looking better now. Will post more later

I’m glad to be back, Derrick. And another great review of a book I shall get my local magic book lady to find for me. Have a quick browse to see what it is I like. https://www.facebook.com/theknownworldbookshop/

What an excellent local resource

That was a great critique and summary; I will have to find this book. I appreciate the fine writing style.

Thank you very much, Cynthia. You would like it

Hello Derrick, thank you for this interesting commentary on a book I haven’t read. I agree with you about the illustrations. I am an artist who likes detail.

Thank you very much, Robbie

The first illustration on the cover is perfectly evocative, so it’s too bad the rest are not for me. However, your description is evocative enough. I love your included quotes, and the skill displayed by the writer. I know you enjoy words well-written.

Thank you very much, Crystal. I agree about the cover box illustration

Book sounds interesting. Sadly our library doesn’t have this book.

Thanks very much, Rupali. That is a shame