This paragraph from https://viewfromtheback.com/2023/01/20/fridays-tall-tales-3/ by Sheree:

“Manzoni’s masterpiece, I promessi sposi, 3 vol. (1825–27), is a novel set in early 17th century Lombardy during the period of the Milanese insurrection, the Thirty Years’ War, and the plague. It is a sympathetic portrayal of the struggle of two peasant lovers whose wish to marry is thwarted by a vicious local tyrant and the cowardice of their parish priest. A courageous friar takes up the lovers’ cause and helps them through many adventures to safety and marriage. Manzoni’s resigned tolerance of the evils of life and his concept of religion as the ultimate comfort and inspiration of humanity give the novel its moral dimension.The novel brought Manzoni immediate fame and praise from all quarters, in Italy and elsewhere.”

took me back to my copy of this work, last read in 1969.

Enough time had passed for me to have entirely forgotten the book’s story, so I am grateful to have been prompted to revisit this work which is so much more than the echoes it bears of Scott, Thackeray and Dickens. The text contains by quotation an acknowledgement of his debt to Shakespeare whom he judges to be a master of feelings and the human heart.

Just as we, often too early, are expected to read and learn quotations from the Swan of Avon, so Italian children do the same with this novel. Just as gems from Shakespeare have entered our language and are often quoted without knowing the source, so it is with what we have translated as “The Betrothed”.

Considered as a linguistic influence on the Risorgimento, Manzoni died just before the reunification of the various states of the Italian peninsular.

As he set out on this project which was to occupy the central years of his life, the author expressed his aims and his reason for choosing the Counter Reformation period as his major focus, in a letter to a friend: “The memoirs we have from that period show a very extraordinary state of society; the most arbitrary government combined with feudal and popular anarchy; legislation that is amazing in the way it exposes a profound, ferocious, pretentious ignorance; classes with opposed interests and maxims; some little-known anecdotes, preserved in trustworthy documents; finally a plague which gave full rein to the most consummate and shameful excesses, to the most absurd prejudices, and to the most touching virtues.” This gives an example of his flowing prose, reflecting his passion, reason, and humanity.

He certainly resembles Shakespeare in his mastery of characterisation; his understanding of a wide range of human nature, its conflicts, its strengths, its weaknesses, and its capacity for tenderness, loyalty, and overcoming obstacles. His insight into the minds and emotional life of his persona is more complex than that of Dickens, whose grasp of history he matches.

In fact his research into the events of the period are so thorough as to make this central section somewhat tedious. He explains his purpose for its inclusion as offering essential insight into the life situations of his protagonists.

His subtle humour pervades the book. Either Manzoni himself or our translator favours simile over metaphor, as evidenced by plentiful examples in much excellent, at times poetic, detailed description of urban and rural life and contrasting environments; in particular the distressing effects of living and dying through famine, war, strikes, and plague. We are given insight into mob psychology, which the author gained from personal experience. This was a time of social disruption, violence, and turmoil.

The resilience of the betrothed pair is admirable in their circumstances, affected as they are by the conflict between church and state, and by blind faith, as well as staunch belief in each other.

Manzoni’s own struggle with Catholicism, to which he returned in later life, perhaps influenced the sudden change of heart and behaviour of the Unnamed, who forges a beneficial relationship with a revered Cardinal.

I hope I have not given away too much of the story to spoil it for any readers who may wish to follow my recommendation and pick up the book for themselves.

My 1969 edition is that of The Folio Society. The translator, who has provided a valuable and informative preface, is Archibald Colquhoun. I would be unable to read the original but this does seem to be a faithful rendition.

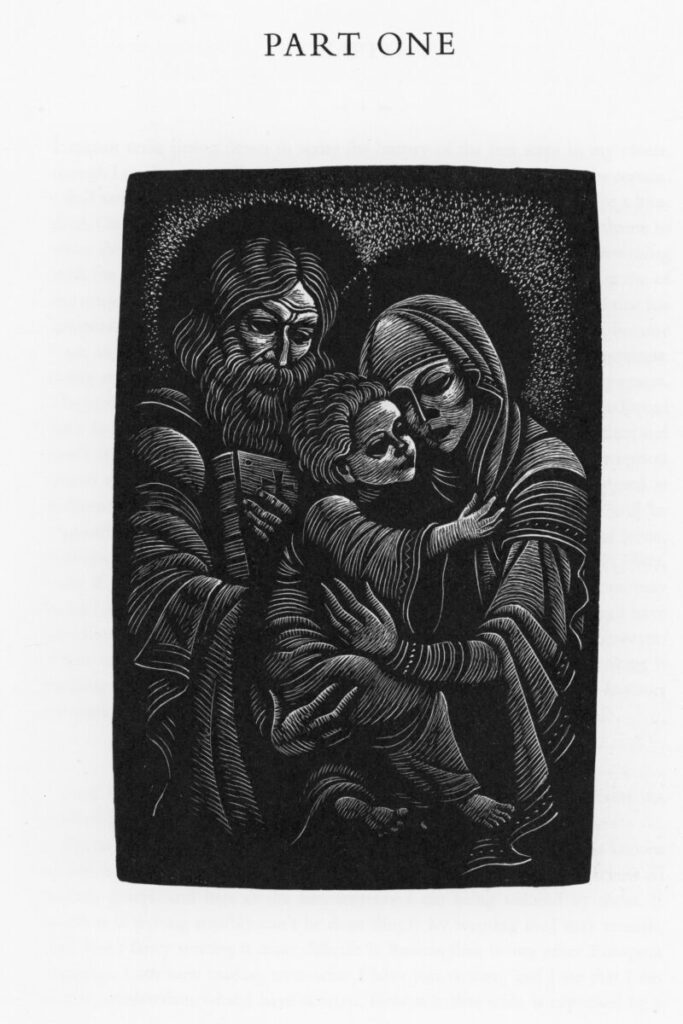

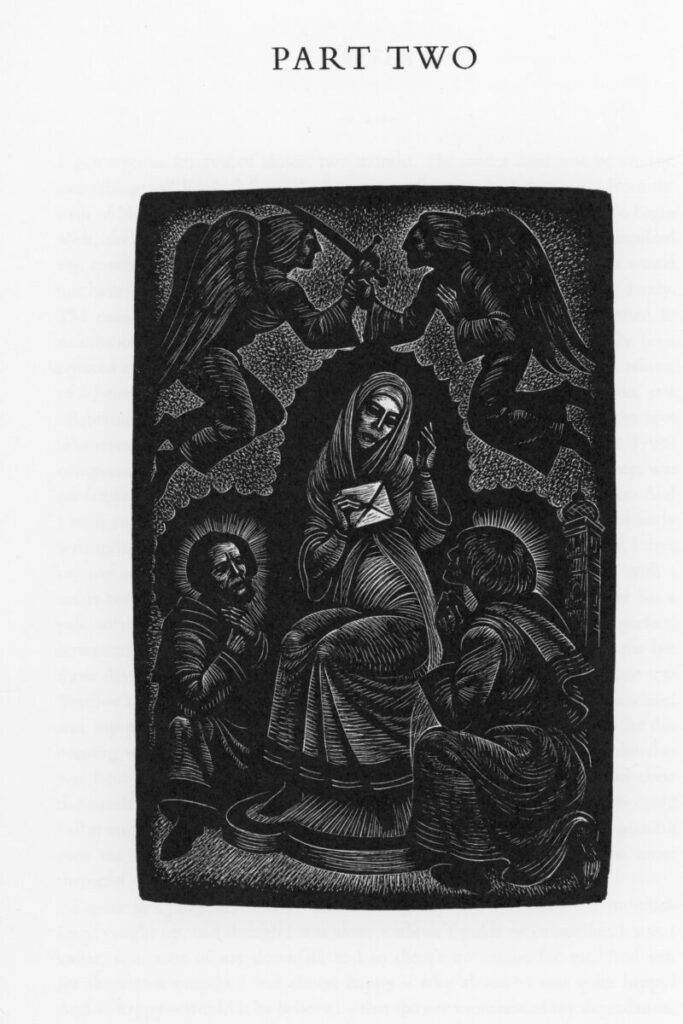

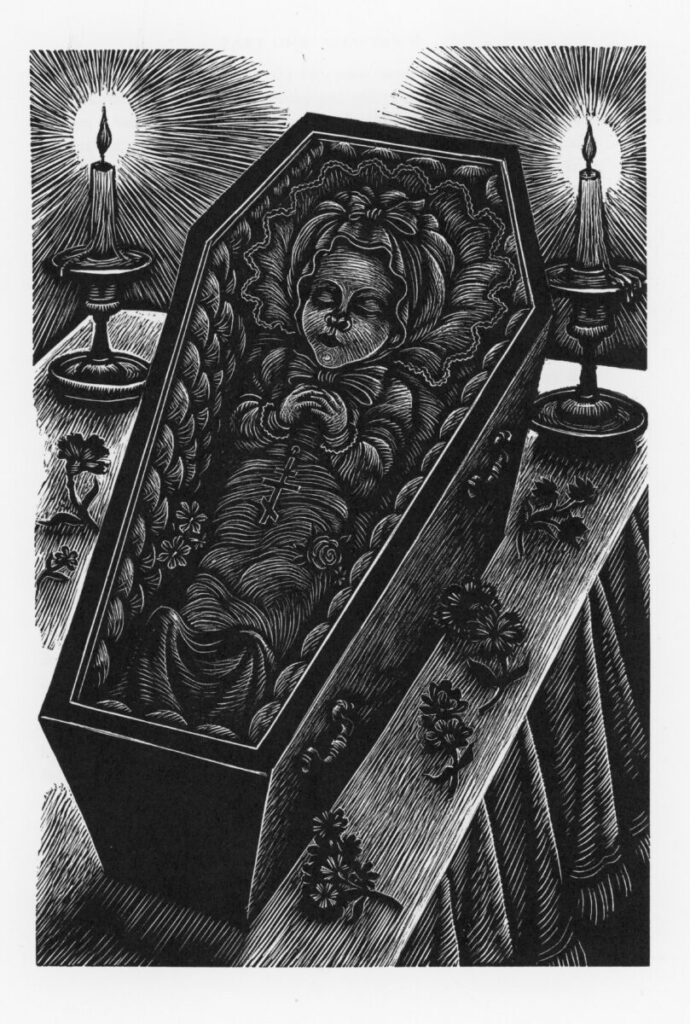

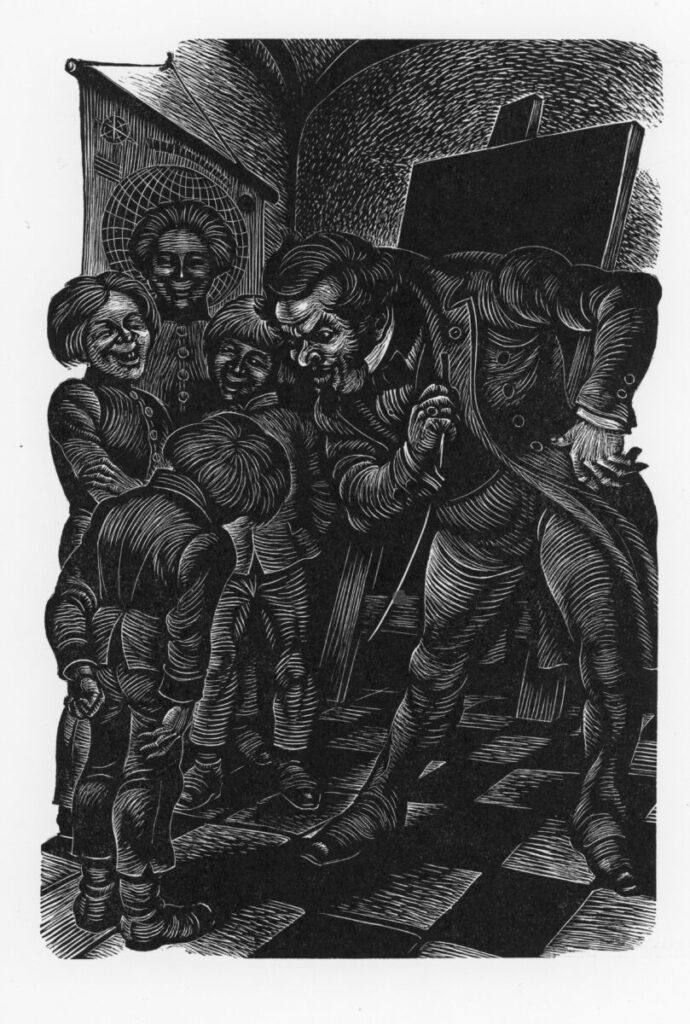

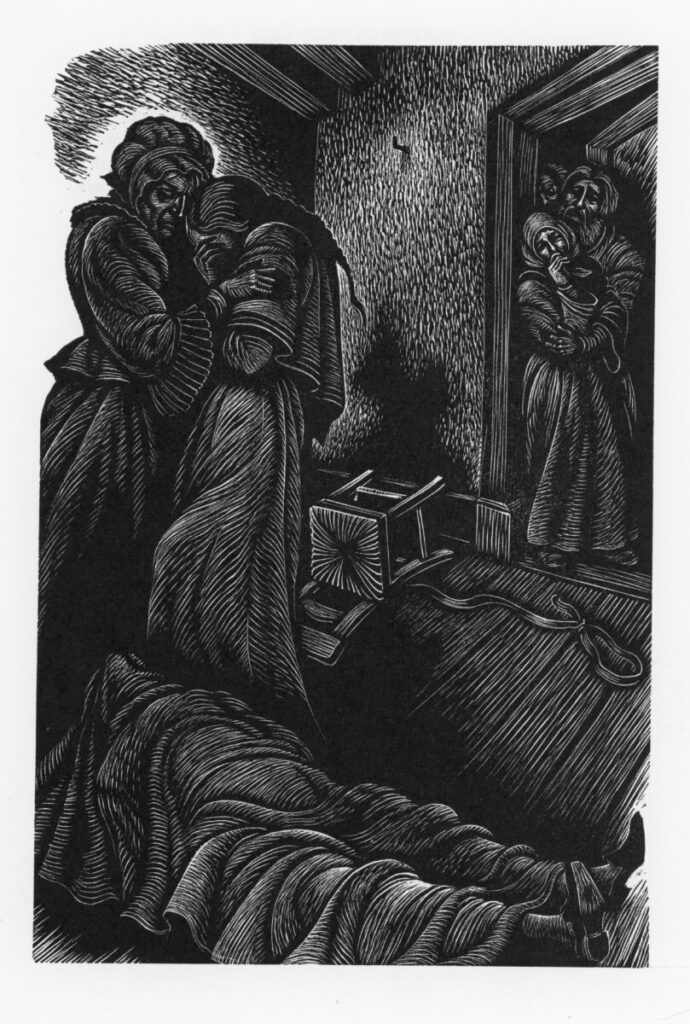

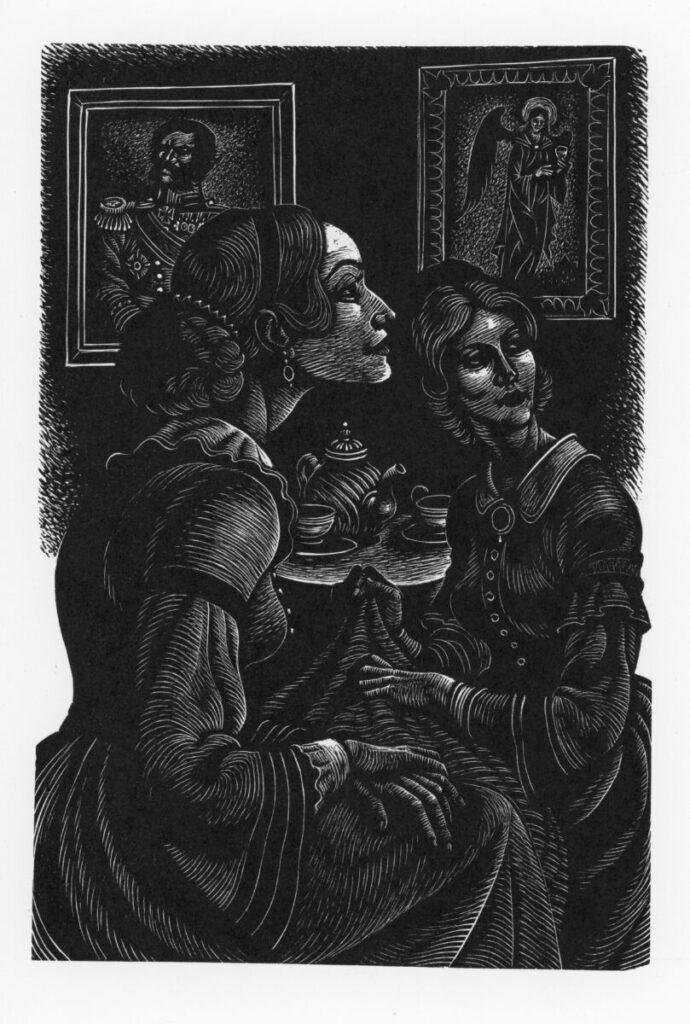

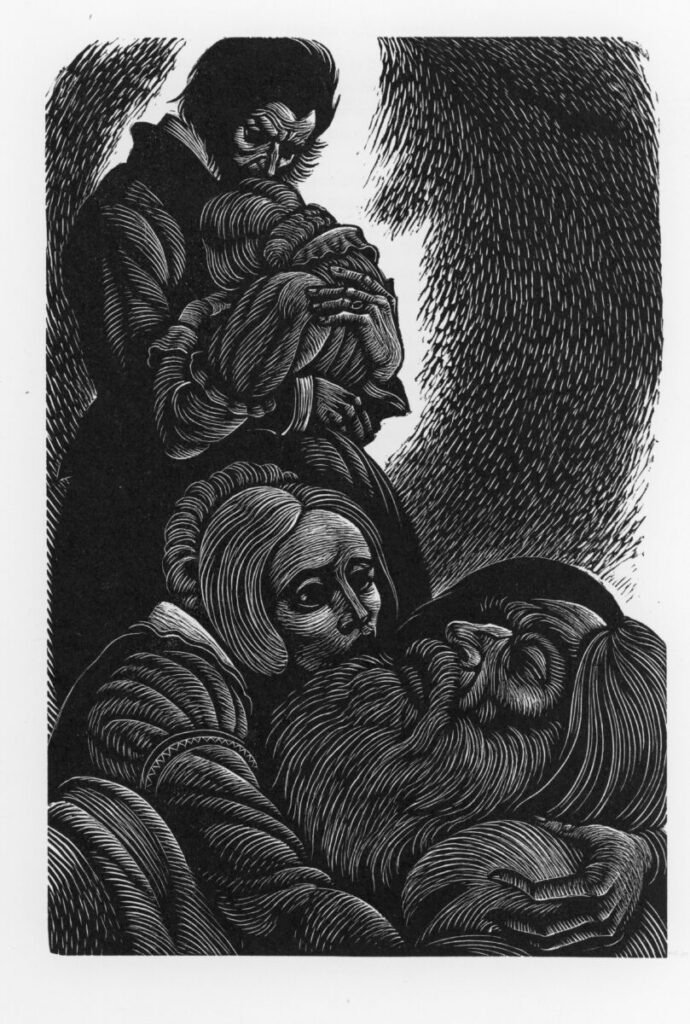

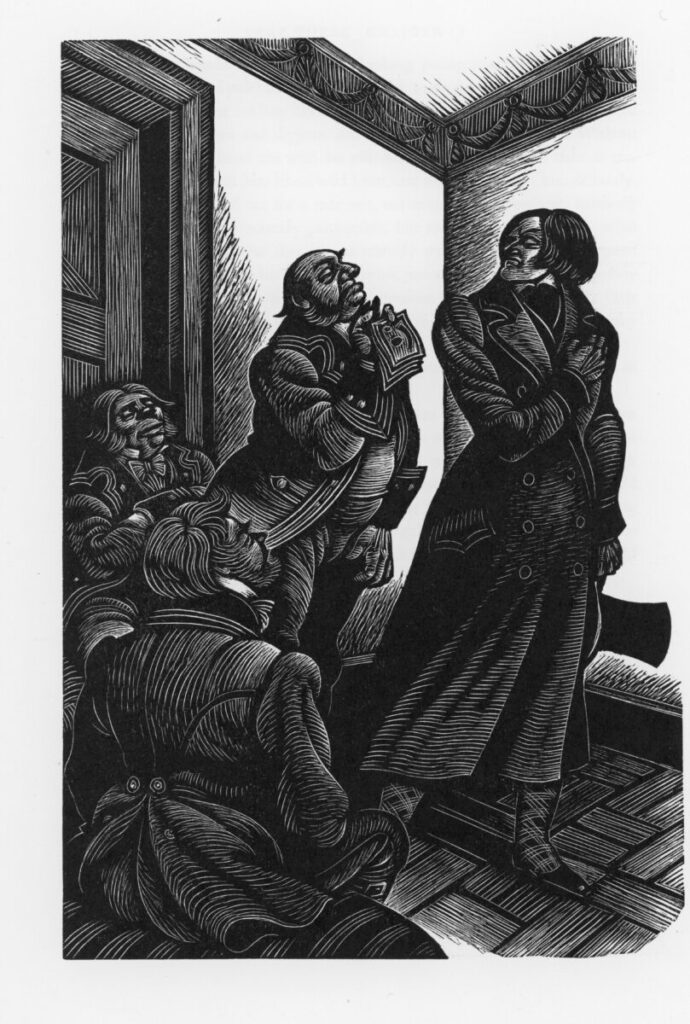

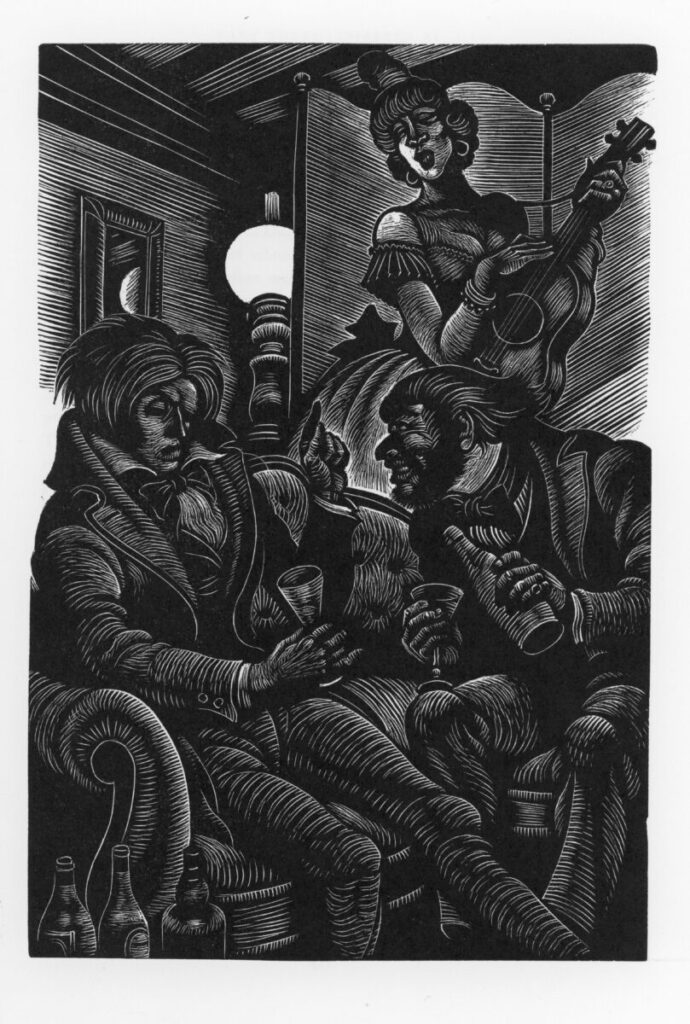

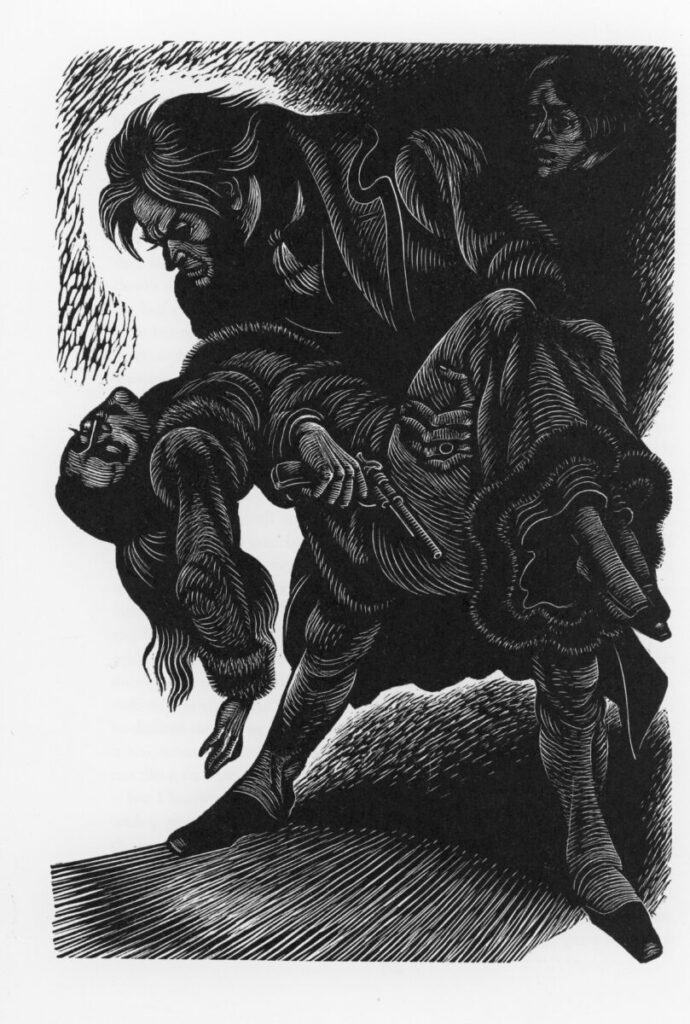

Here is the frontispiece and Title Page.

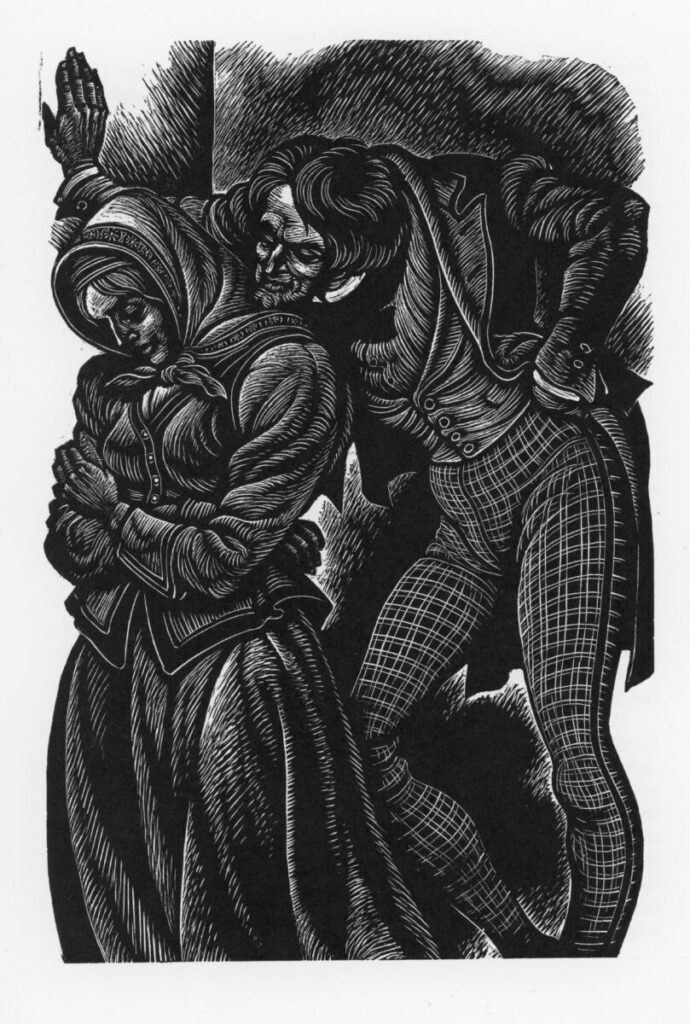

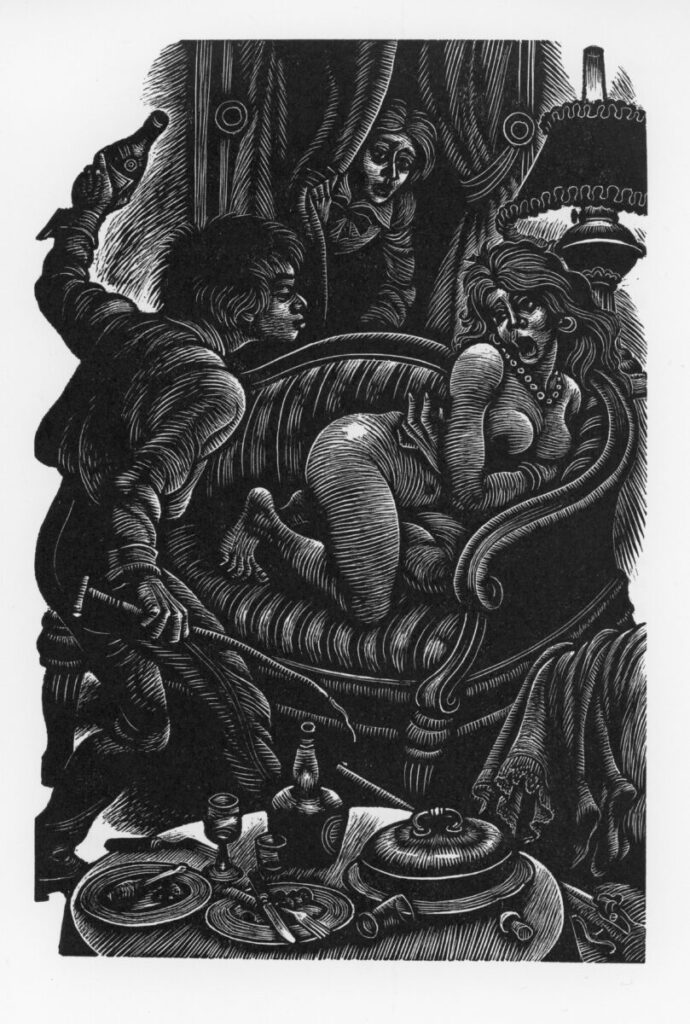

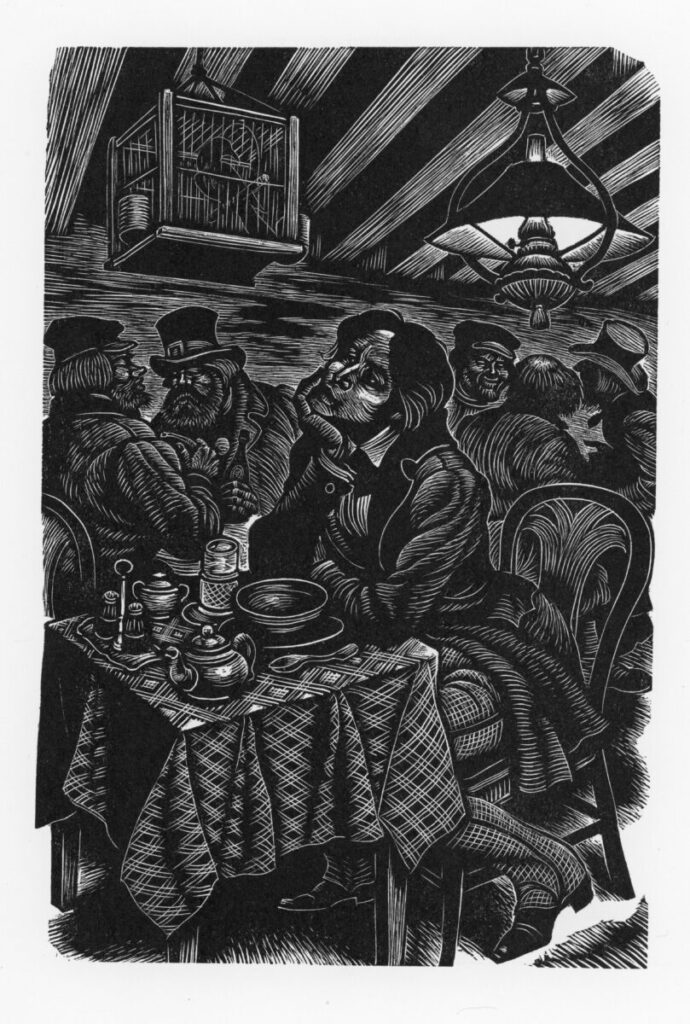

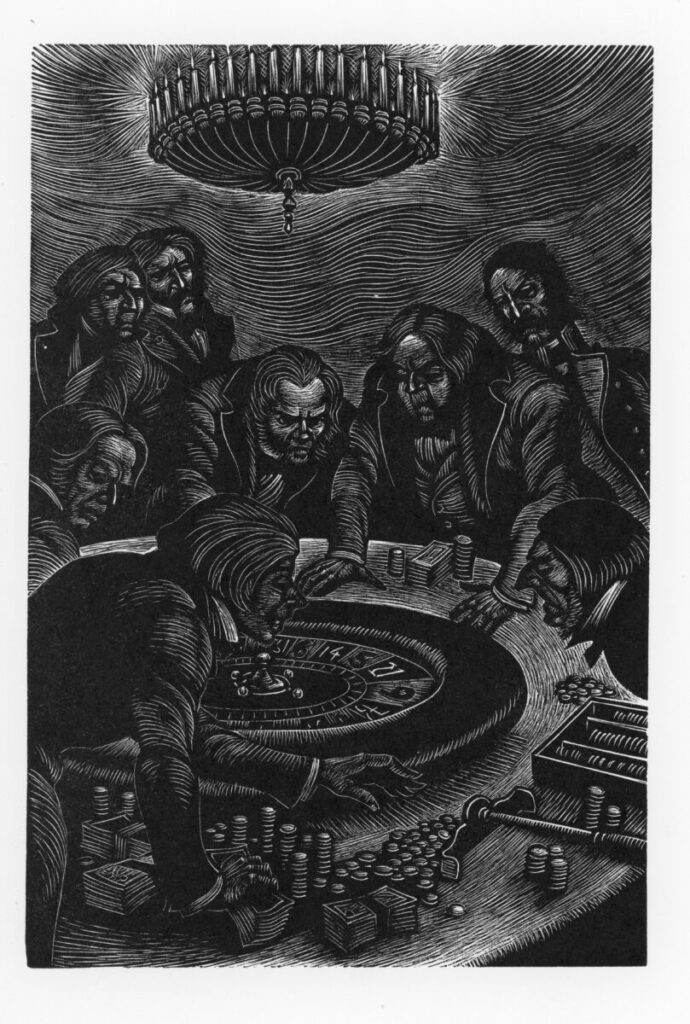

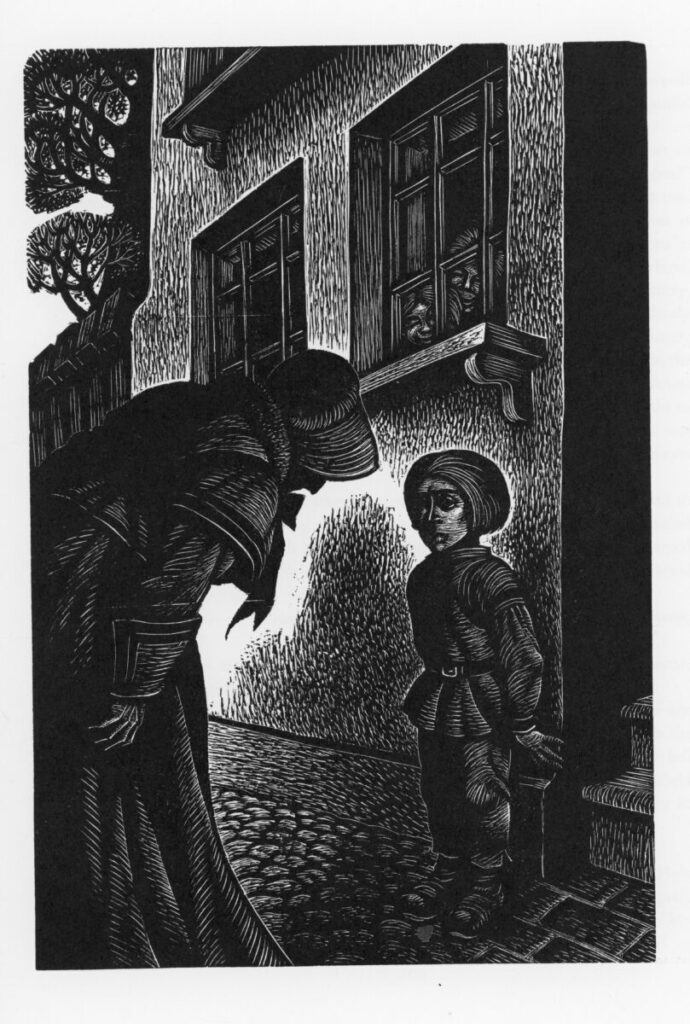

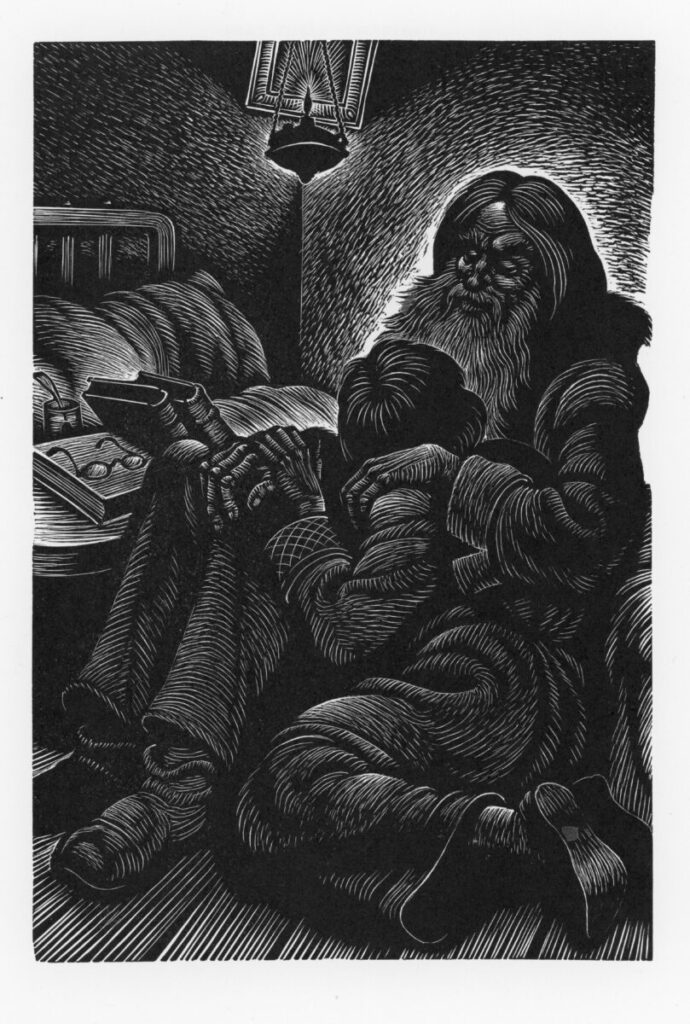

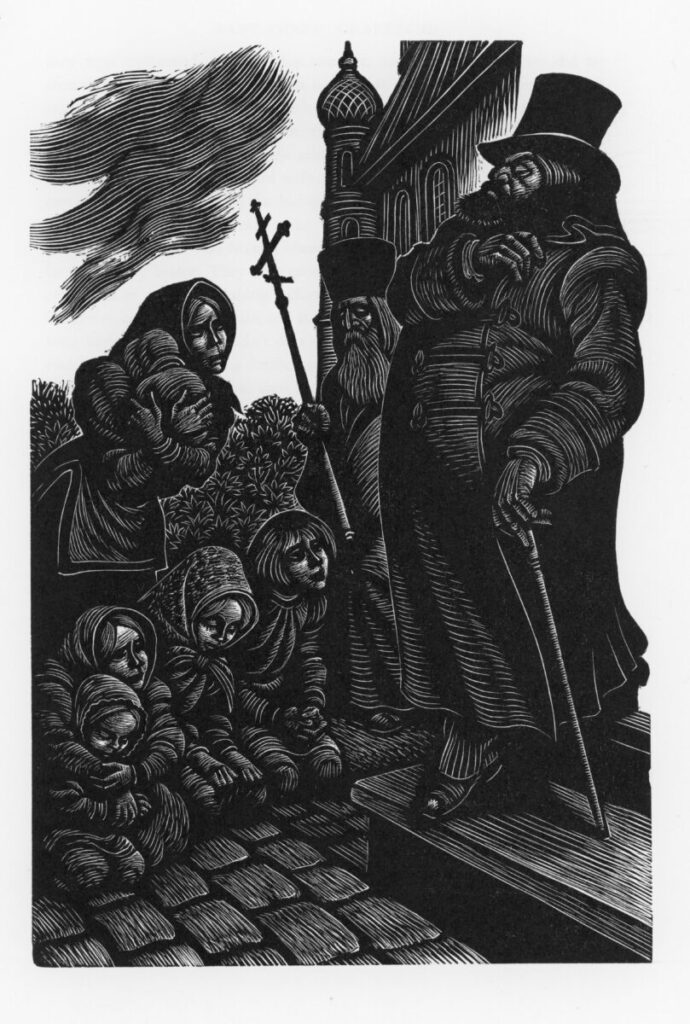

The sharply lined and detailed drawings by Eric Fraser have the incised quality of such as scraper board.