Early today I watched the Channel 4 broadcast of the first day’s play at the fourth Test Match between India and England.

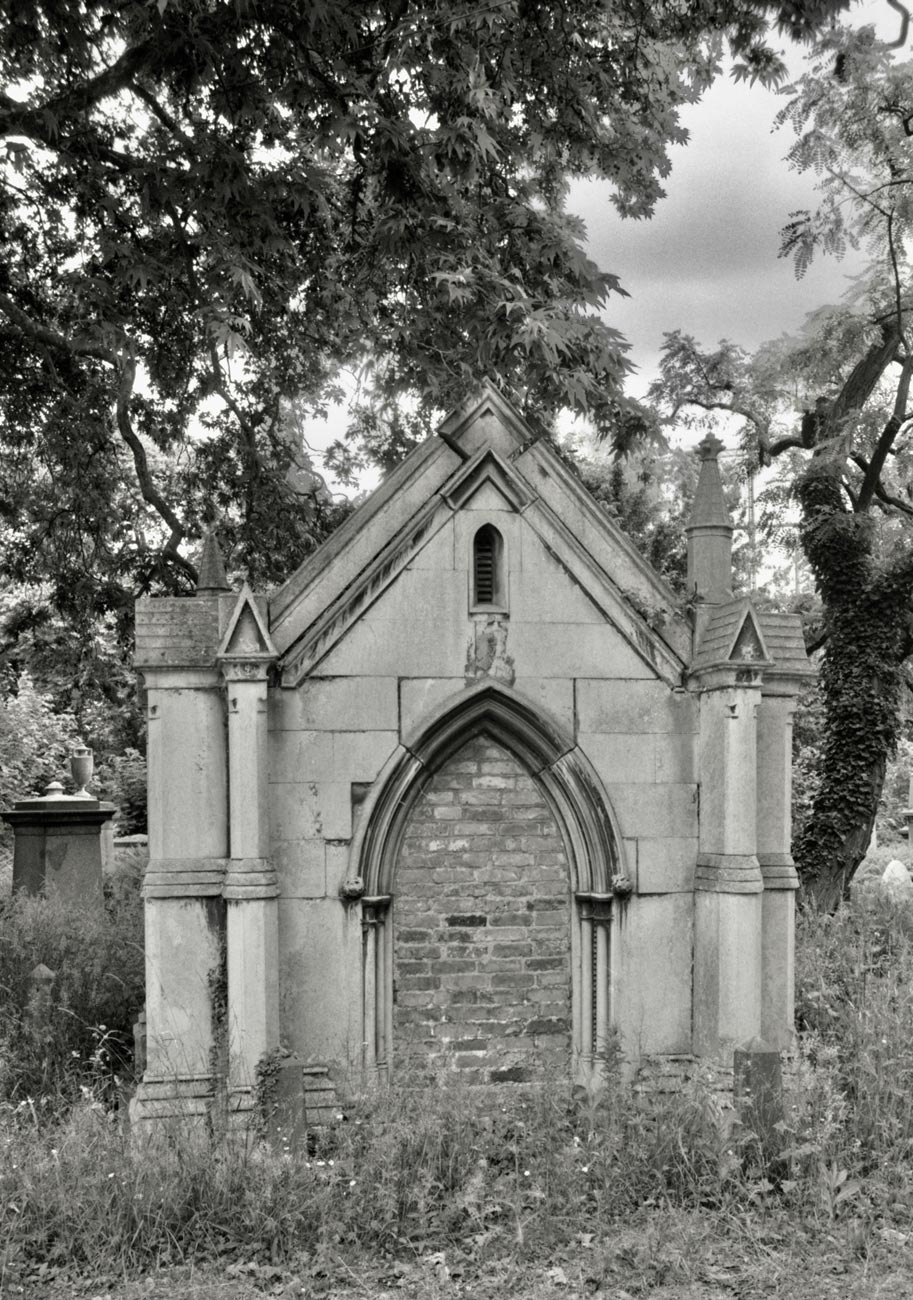

After lunch I scanned some more colour slides. This is the last of those from Kensal Green Cemetery, made in May 2008. A lengthy preview of Mark Olden’s ‘Murder in Notting Hill’ features the inscription of this grave of Eugene Henry Draggon, known as Jingles. https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Murder_in_Notting_Hill/LKRblqxEUDkC?

Late in December of 2008 I received a phone call from an excited John Turpin, who wrote the text of ‘The Magnificent Seven’ informing me that there was a splendid sunset at Kensal Green and urging me to visit and photograph it before it disappeared. I duly obliged.

The last picture in this gallery contains

the rather weather worn memorial to Thomas Taplin Cooke.

According to Wikipedia, he ‘was born in Warwick in 1782 the son of Thomas Cooke and his wife, Mary Ann.[3]

He took over his father’s circus around 1810. In the autumn of 1830, following a pleasurable visit from King William IV and Queen Adelaide, the company adopted the name “Royal Circus” and retained this name for the remainder of their existence.[1]

In 1835 the circus had a semi-permanent structure in Edinburgh (a circular timber structure) at the north end of Lothian Road but this had to be later moved when the Caledonian Railway was built. At this point (c.1850) the circus moved to Nicolson Street, where it was later surplanted by the Empire theatre (now known as the Festival Theatre).[4]

In 1836 he chartered “The Royal Stuart” from Greenock[5] and two smaller vessels to convey the whole circus to America. 40 of the 130 artists were members of the Cooke family. This extended trip included prolonged programmes in New York, Boston and Walnut Street Philadelphia. At this stage their “pattern” was to erect a large circular building of a temporary nature (normally in wood). It is unclear how long this American tour was intended to last, but it met an abrupt end during their stay in Baltimore on 3 February 1838, when the Front Street Theater burnt down (note- there is some confusion as two “Front Street Theaters burnt down within 5 weeks of each other: Baltimore on 5 Jan 1838, Buffalo on 3 February 1838).[6] The Cookes lost 50 horses and many items of wardrobe and props in this fire.

It appears that the circus had been used to operating from large theatres up to this point. Either during the American tour or following the fire disaster, Taplin Cooke, had a very large circular tent constructed. After a few more months in Philadelphia, he returned to Britain in the summer of 1838 with this large tent, which freed up the possible locations for the circus.[1]

One very dramatic equestrian show was “Mazeppa” based on a poem by Byron, first performed in Philadelphia in 1838 and still playing until at least 1843 when it was showing at Birmingham in England. This concept was borrowed from Andrew Ducrow‘s show Mazeppa of 1831.[7] In 1846 a similar style of show was based on the life of Dick Turpin.’

Cooke died in 1866. His memorial contains a mourning horse and a child reading.

There is further information on details depicted here in the post ‘Where Is The Body?’ The sphinx is from the grave of the above mentioned Andrew Ducrow, and the Raj Guard from that of Gen. Sir William Casement.

A black and white image of William Mulready containing an explanatory plaque appears in ‘Ninon Michaelis’

I know neither whose hat and gloves have fallen with their broken plinth, nor what is being celebrated in this intriguing bas relief.

This evening we repeated yesterday’s excellent Jalfrezi dinner, complete with beverages, which meant I opened another bottle of the Coonawarra Cabernet Sauvignon, and toasted Yvonne.