Early this morning, a representative of Norman’s Heating visited to assess for quotation our requirements for a new oil tank. The good news is that we don’t need such a big container. We await the estimate.

After lunch Jackie drove us all to Ringwood, where we left Flo, Dillon, and Ellie while she and I took a trip out of the forest where we stopped beside

a bridge over the River Avon on the road to Harbridge.

Every year the Avon around the area overflows its banks. This is just

one spot where water meadows are created.

An egret was happily foraging there.

The little community of Harbridge has such a long history that I have included the following paragraphs for those who are interested. You may wish to skip these and scroll down to the churchyard pictures.

‘Herdebrige (xi cent.); Hardebrygg (xiii cent.); Haberigge (xiv cent.); Harebrigg (xv cent.); Hardbridge (xvi cent.).

The parish of Harbridge contains over 4,000 acres, comprising 650 acres of arable land, 986½ acres of permanent grass and 356½ acres of woodland. (fn. 1) The height above sea level is for the most part above 100 ft. and below 200 ft. The soil is sandy, the subsoil gravel, which has been considerably worked. (fn. 2) The western and south-western parts of the parish comprise the great uncultivated tracts of Plumley Heath with its tumuli and Nea Heath. In the south-east is Somerley, the seat of Lord Normanton, with its magnificent picture gallery and its park of 900 acres. Nearly the whole parish together with Ibsley and Ellingham belongs to Lord Normanton’s estate.’

‘The little village of Harbridge, with its church, lies about 2 miles north-east of Somerley, at the edge of the low meadow land to the east of the River Avon. North again are Harbridge Green and North End Park and Farm. Old Somerley is on the northern border of Somerley Park.’

‘In 1086 HARBRIDGE was held of the king by Bernard the Chamberlain, having been held by Ulveva in the days of the Confessor. The assessment had fallen from 5 hides to 3 hides and 1 virgate. (fn. 4) The subsequent history of Harbridge is not easy to unravel. Gilbert de Clare Earl of Gloucester and Hertford, the last of the Clares, was receiving a rent of 25s. 8d. held of the king by knight service at his death in 1314. (fn. 5) This was then committed to the charge of Lawrence de Rustiton, and afterwards of Richard de Rodeneye, Ithel de Keyrewent and Richard de Byflet, keepers of the earl’s lands, (fn. 6) the places of the last two being subsequently taken by Bennet de Cokefeld and William de Aylmere. (fn. 7) It was probably by virtue of the Clare possessions that the king’s name occurs in the Nomina Villarum of 1316. (fn. 8)‘

‘The king’s parcenary in 1316 was Isabel de Acton. (fn. 9) Her holding may be traced in the messuage and virgate the reversion of which Sir John Poyntz conveyed to Sir John de la Hale and his heirs in 1364. (fn. 10) John Palmer was then holding the estate of the hereditament of Poyntz; after his death it was to remain to Joan wife of Sir John de Acton, deceased, and after her death to remain to Poyntz or by the terms of the conveyance to Sir John de la Hale.’

‘By the early part of the 15th century Harbridge, then known as a manor, had come into the hands of a Henry Smith who was unjustly disseised by John Poole. (fn. 11) However, in January 1500 Thomas Poole of Holwall (co. Somers.), a descendant of John, sold and quitclaimed to John Smith of Askerswell (co. Dors.) grandson of Henry, both for himself and Margery, late wife of Thomas Trowe, and possibly sister or mother of Thomas Poole, (fn. 12) all right and title in the manor of Harbridge, together with all the possessions of the late Margery Trowe, and those occupied by Jane widow of John Poole, uncle of Thomas, and by Edith Poole widow. (fn. 13) The full sum due on this sale was not paid off, however, until 1504, (fn. 14) and meanwhile Poole conveyed the premises to Sir John Turbervyle and to Richard Kemer. (fn. 15) Nevertheless Nicholas Smith, heir, presumably, of John, died seised in 1538, (fn. 16) leaving a widow Sybil, on whom Harbridge was settled in dower for life, and a son and heir George. Sybil apparently married as her second husband John Okeden, (fn. 17) with whom she was holding the manor for the term of her life in 1541, (fn. 18) in which year Jaspar Smith, presumably brother of Nicholas, settled all his reversionary right on Thomas Whyte. Sybil died in 1551, leaving as heir her son George Smith before mentioned, then sixteen years old. (fn. 19)However, by 1567 Harbridge was carried by coheiresses Elizabeth and Jane to their respective husbands John Rose and Francis Poyntz. (fn. 20) The remainder was to Ambrose Rose of Ringwood, who sold it in 1601 (fn. 21) to John Wykes of Harbridge. Francis Poyntz quitclaimed to the new lord a few years later. (fn. 22) The Wykeses continued to hold during the greater part of the 17th century. John Wykes had been sequestered in 1649 and in 1654 he was still awaiting redress. (fn. 23) In 1688 Lewis Bampfield and Elizabeth his wife and Margaret Wykes, spinster, were party to a conveyance of the manor, when, however, one John Wheeler seems to have been in actual possession. (fn. 24)Elizabeth and Margaret would seem to have been the co-heirs of the Wykeses and Margaret was probably the Margaret wife of William Bowreman who with her husband and Lewis and Elizabeth Bampfield sold three messuages and land in Harbridge, Ellingham, Hurst, Blashford, Rockford, Ringwood, Lyndhurst, Linwood and the New Forest to Henry Hommige in 1689, warranting him against the heirs of Elizabeth and Margaret. (fn. 25) By 1693 the manor was in the hands of Edward Twyne (fn. 26) and in 1700 Joseph Hussey and Mary his wife sold it to Joseph Gifford. (fn. 27)Early in the 18th century Gifford must have sold the manor to James Whitaker, (fn. 28) who in 1733 conveyed it to Dayrell Hawley. (fn. 29) No further mention of Harbridge Manor has been discovered until 1810, when it was held by Percival Lewis. (fn. 30) Soon after that it passed to the Earl of Normanton (see Somerley) and now forms part of the Somerley estate.’

‘The Punchardons had an estate in Harbridge for a considerable period. In 1263 Robert de Punchardon and Alice his wife quitclaimed from themselves and the heirs of Alice a messuage and a carucate of land to William de Punchardon, Maud his wife and Hawis her sister and the heirs of Maud and Hawis. This seems to have been the same estate of which in 1375 John de Boyland of Eling and Alice his wife, holding it of the hereditament of Alice, conveyed a moiety to William de Athelyngton and a moiety to Oliver de Punchardon, the whole estate being in the actual possession of John Bereford and Denis his wife for the life of Denis. (fn. 31) Oliver de Punchardon died seised of lands there in 1417. (fn. 32) Like Ellingham (q.v.) the Punchardon moiety of Harbridge passed to the Okedens, (fn. 33) and in 1604 William Okeden sold it to Thomas Worsley, (fn. 34) who died seised in 1620, (fn. 35) leaving an infant grandson Thomas Worsley as his heir. Thomas Worsley’s daughter Barbara was the wife of a William Bowreman, whose namesake, possibly himself or a son, was dealing with land in Harbridge in 1689. (fn. 36) From that date this moiety of Harbridge undoubtedly merged in the manor proper and belongs at the present day to the Earl of Normanton.’

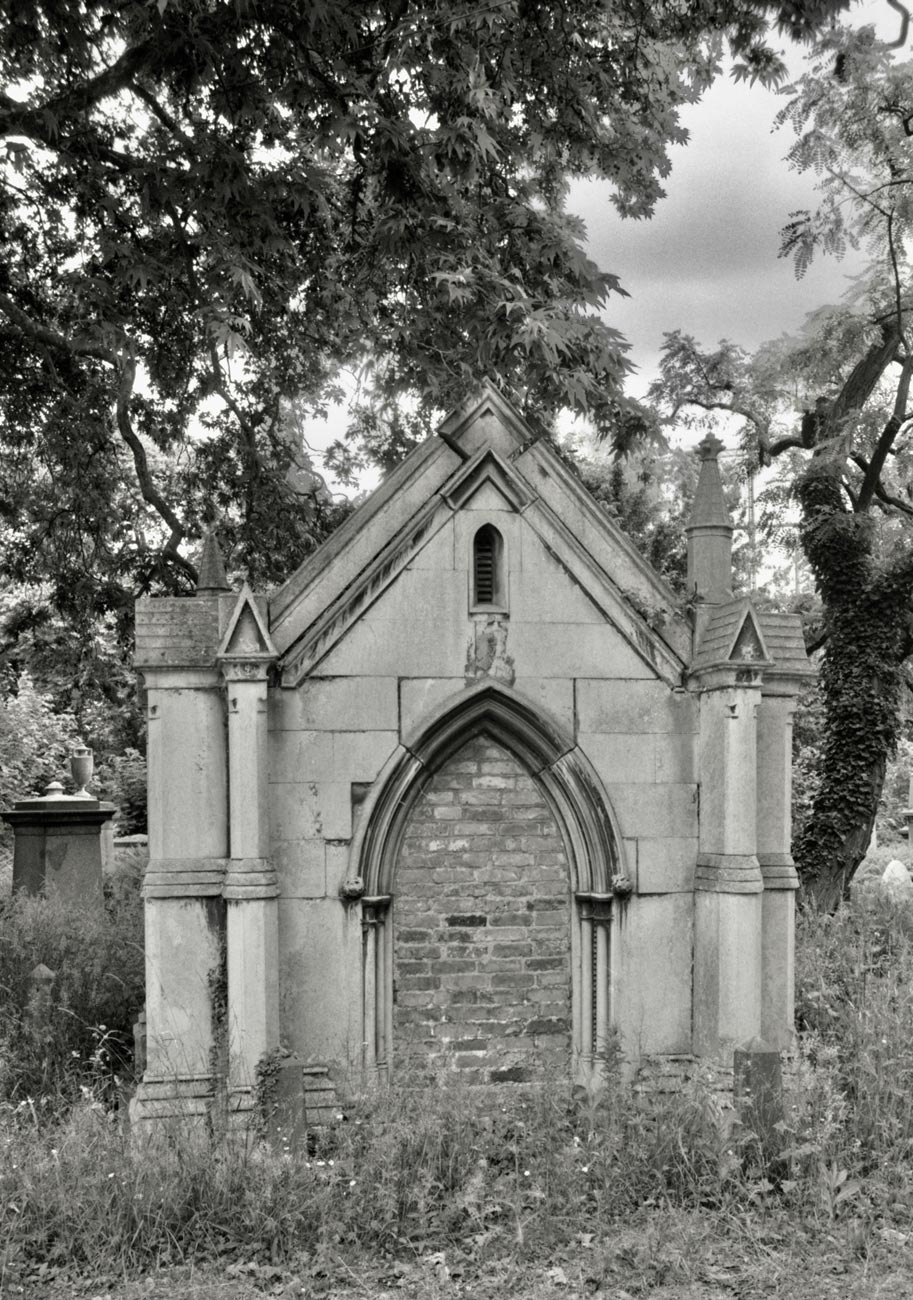

‘The church of ALL SAINTS is an ashlar-faced building consisting of chancel, nave and west tower, rebuilt in 1838 in 15th-century style, but part of the tower masonry appears to be older. There is a small wall tablet to Edward Dodington ob. 1656, with a quartered shield.

The bells are three in number, all by Thomas Mears, 1839.’

Extracts from https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/hants/vol4/pp604-606#p1

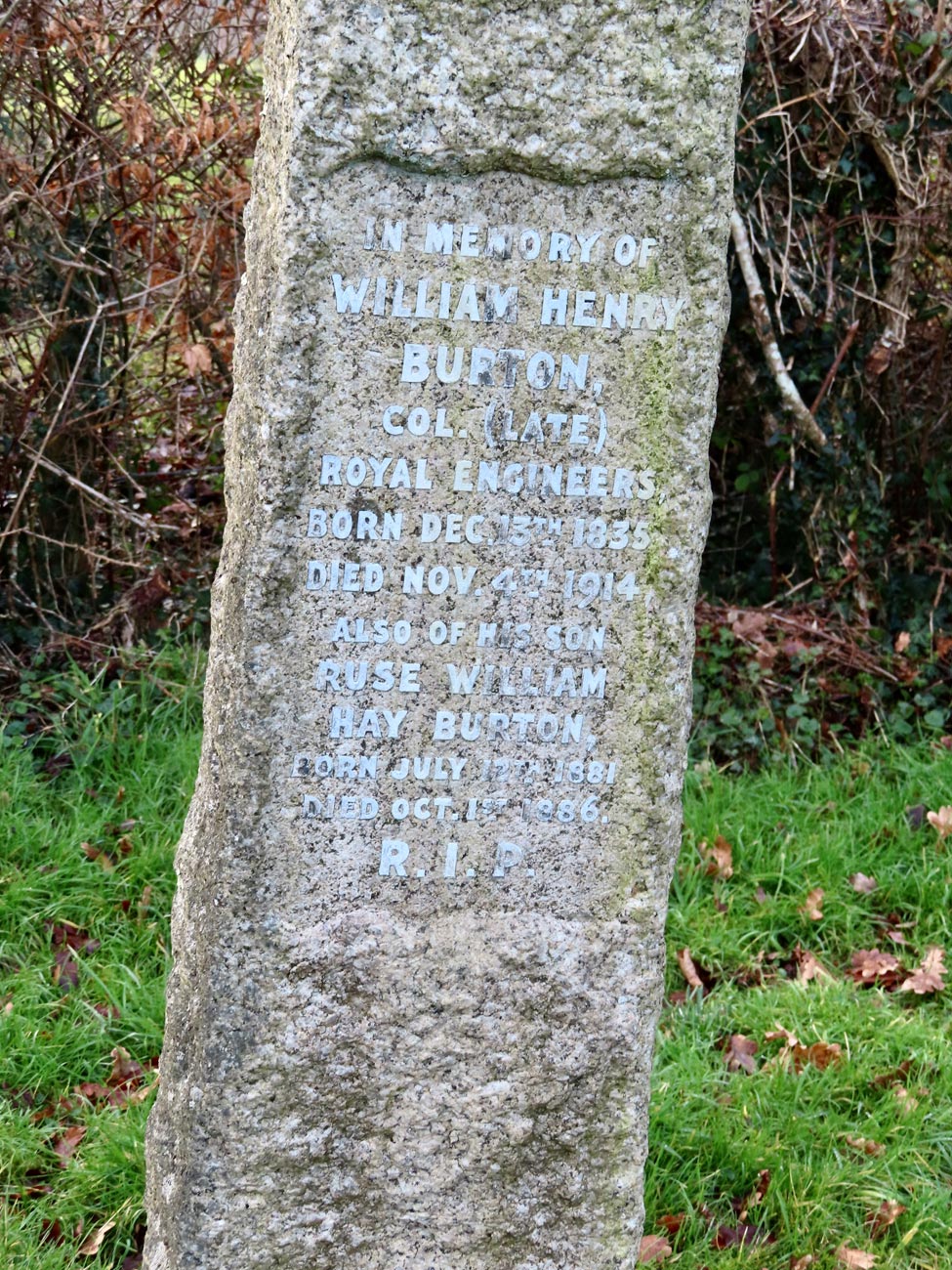

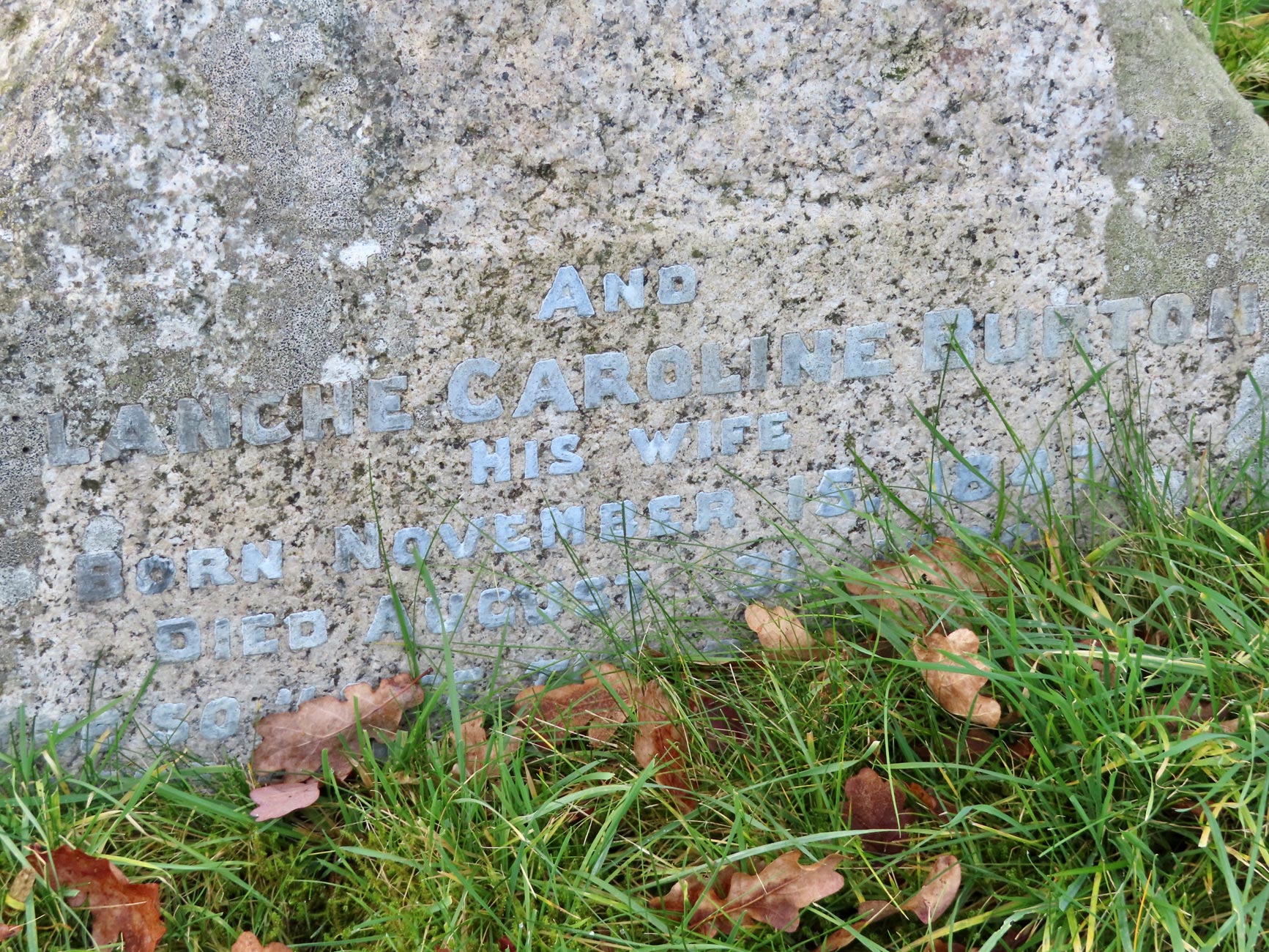

The lichen covered gravestones are largely indecipherable, although there are good number of the Pratt family. Many seem to bear very early Victorian dates, and look even earlier. There is a phalanx of four shaped yews guarding the entrance path, and one of greater age round the back. Snowdrops are in abundance.

This evening we all dined on Mr Pink’s fish, chips, and mushy peas, Garner’s pickled onions, and Tesco’s sliced gherkins. Jackie and I both drank Grüner Veltliner 2020.