On a visit to The Priest’s House Museum at Wimborne in November 2013 I entered the Victorian kitchen, laid out with all its accoutrements, complete with an elderly woman with a shawl round her shoulders and a book in her hands before a lighted kitchen range.

This truly was an authentic tableau, with just one figure of the period in situ. Then she spoke. I laughed wholeheartedly, and said I had thought she was a model. She told me that a small boy earlier had thought the same thing, and had been most surprised when she greeted him.

This was Margery Ryan who was clearly one of the museum’s volunteers, and a wealth of information, including that of the children’s activities. They were encouraged to make toast with one of the toasting forks hanging beside the kitchen range, just as I and my siblings had done by an open fire in our sitting room at Stanton Road. I remembered how, on a coal fire, you had to take your hand away every now and again because it got pretty hot. There were no electric toasters.

The range in this photograph is exactly the same as the one we used throughout my childhood. Although a gas cooker came later, Mum would have heated a kettle like that on this stove. She had no electric iron in 1944. An iron one was also heated on the stove and, a protective cloth wrapped around the handle, applied to the family washing she had undertaken by hand, using bowls, soap, scrubbing brush, and tub, such as those in this picture of a mangle into which

sheets, in particular, were placed between two rollers, and you turned a handle in order to squeeze and therefore rinse them. One day when we were very small Chris left his finger in as I turned the handle. Fortunately his bones must have still been soft enough to be re-inflated.

I have no idea how Mum dried our clothes when it was too wet to hang them out on the washing line in the garden. There was, of course, neither washing machine nor drier.

Mum was most inventive with very limited resources.

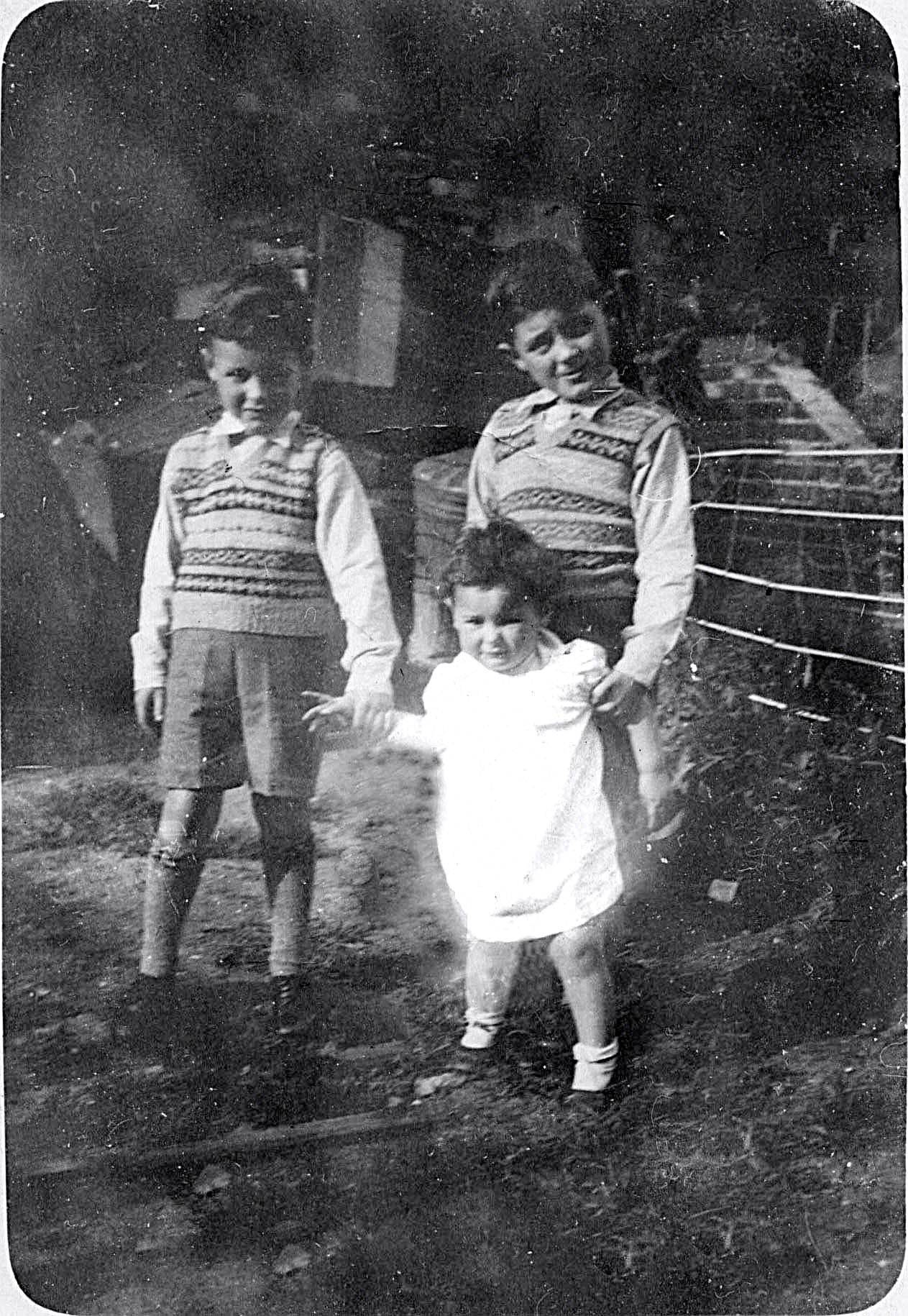

This photograph depicts the first trio of our parents’ offspring, namely me, Chris, and Jacqueline, taken, I imagine, in the summer of 1948, probably in Durham, and if so by our grandfather. We were very proud of those Fair Isle jumpers which were all the rage then, and continue to be made today. I don’t think they were available at that time from outlets such as Laura Ashley. They were, and still are, hand-knitted in the island in northern Scotland from which they take their name. The genuine article is no longer generally available for sale, the market having been swallowed by mass production. Their geometric patterns remain popular.

Ours were not from the Fair Isle. They were, like all our other clothes, made by our mother. A couple of years later, my grandmother taught me to knit. I made endless scarves. When I say endless, this is a literal statement. They had no endings because I didn’t know how to cast off and had to wait for Grandma Hunter to be in the mood to do it for me. They had usually got a bit straggly by then, and it wasn’t good for her temper.

I was, however, fascinated by the making of the patterns and progressed to designing, on squared paper, images for Mum to knit.

This, as far as I remember, involved different symbols for different stitches, with the use of appropriate colours. Joseph was to follow me in this, and I believe a Goofy design that Mum reproduced on a jumper for several family members was drawn on graph paper by him not so very long ago. He obviously shared his brother’s interest in going beyond the geometric.

My own early masterpieces, long before anyone thought of recycling, have most likely wound up in some landfill somewhere.

Alternatively, if, like Mum’s dressmaking patterns, cut into squares and threaded on a string, the material was thin enough to be used for toilet paper, they could have come in handy in the loo.

Our bedrooms, there being no central heating, and coal expensive, were unheated. This could become nose-tinglingly cold with icy sheets, especially if you had wet them. The beauty of it, however, was that you could wake in the morning to frost patterns,

like this from our car windscreen in January 2017, on the inside of your windows.

Dishes were washed and dried by hand.

There was no fridge. The hot summer of 1947 was particularly problematic in keeping milk and butter from going off. Bottles of milk were kept in cold water in the kitchen sink. Butter simply became runny.

I couldn’t bear that, so I would only eat Echo margarine, the single oily spread that was at all impervious to the heat. This, of course, is really only fit for cooking, and no way would I consider it today.

Many of today’s children carry their own mobile devices with which they may make and receive telephone calls; send and receive texts or e-mails; watch films; and goodness knows what else may be possible by the time this tale is published. Imagine an era, if you can, in which most people didn’t have a telephone in their home, and if they did it was rented from the Post Office, attached to a cable embedded in the wall, on a line shared with neighbours who, if so inclined, could listen in to each other’s conversation.

Personal Computers had not even been thought about.

Our family never had a telephone. I was eighteen when I first used one at work. It scared the life out of me every time it rang.

Although Dad was a driver in the Army we never had a car. Neither did others in our street.

Most people had no television, and those on the market possessed very small screens in grainy black and white, often with stripes rolling up and down the picture. They usually only worked if the aerial was in the correct position to receive the signal, often held in someone’s hand. If there was no available aeriaI a coat hanger would do. I was fifteen when my parents were first given a second-hand set.