This morning I produced an A3 print of his choice for the paraglider from “Sunset Dancing”. Now we are back in National Lockdown handover will probably have to wait a while.

In the meantime Jackie photographed the farmer across Christchurch Road trimming his hedge. He didn’t really cause any disruption to traffic, although it was a little tight at times. The owls on our front fence were undisturbed. Note the thriving carpet rose.

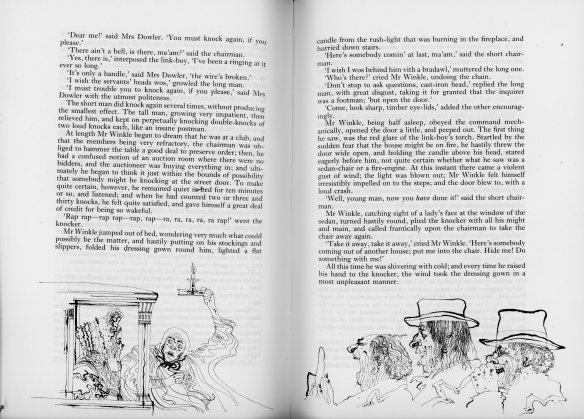

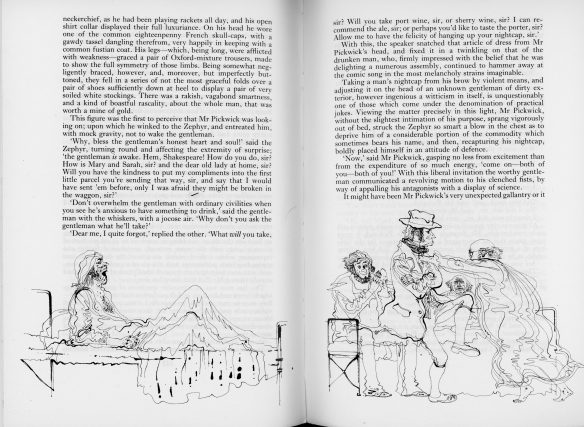

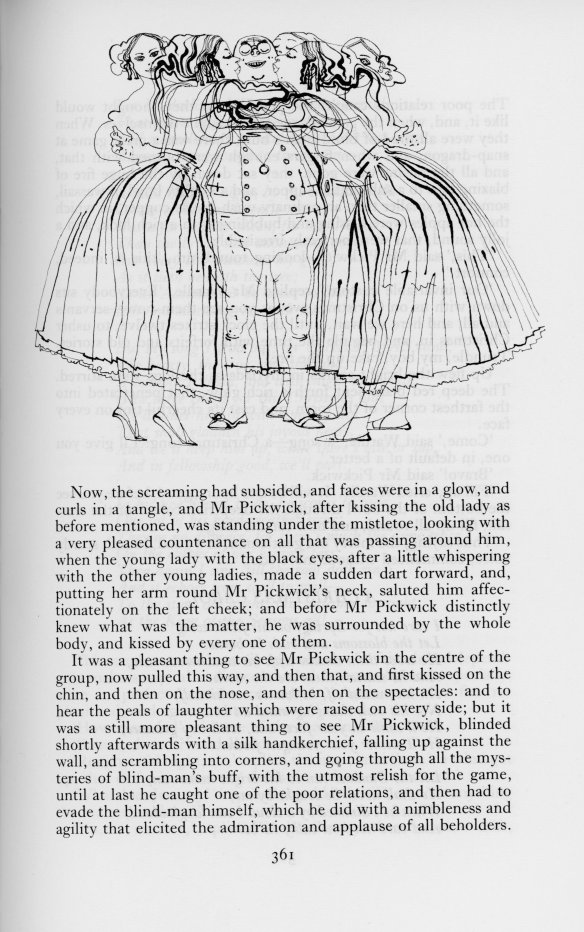

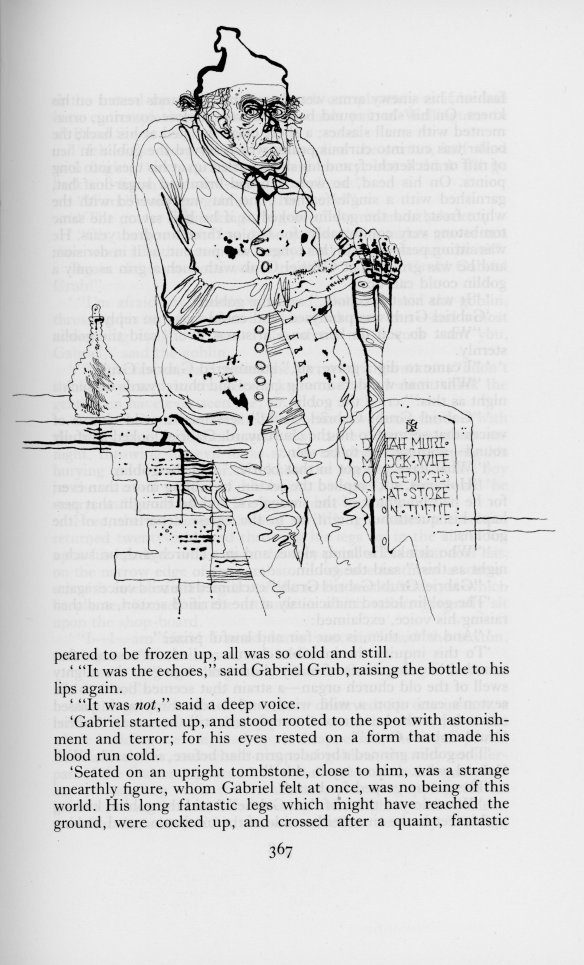

Charles Dickens’s ‘Christmas Books’ is definitely a mixed bag. This afternoon I read ‘The Battle of Life – A love story’, first published in 1846. The narrative begins with a lovely bucolic description and a delightful dance giving us hope for joyful times ahead. There follows a rather boring sequence, more poetic word pictures, and a somewhat far-fetched conclusion, all featuring the author’s entertaining wry humour. Christopher Hibbert, in his introduction to my Folio Society edition, describes this ‘slight but dismal tale’ as a version of relationships and events in the author’s own life at this time. That rings true to me.

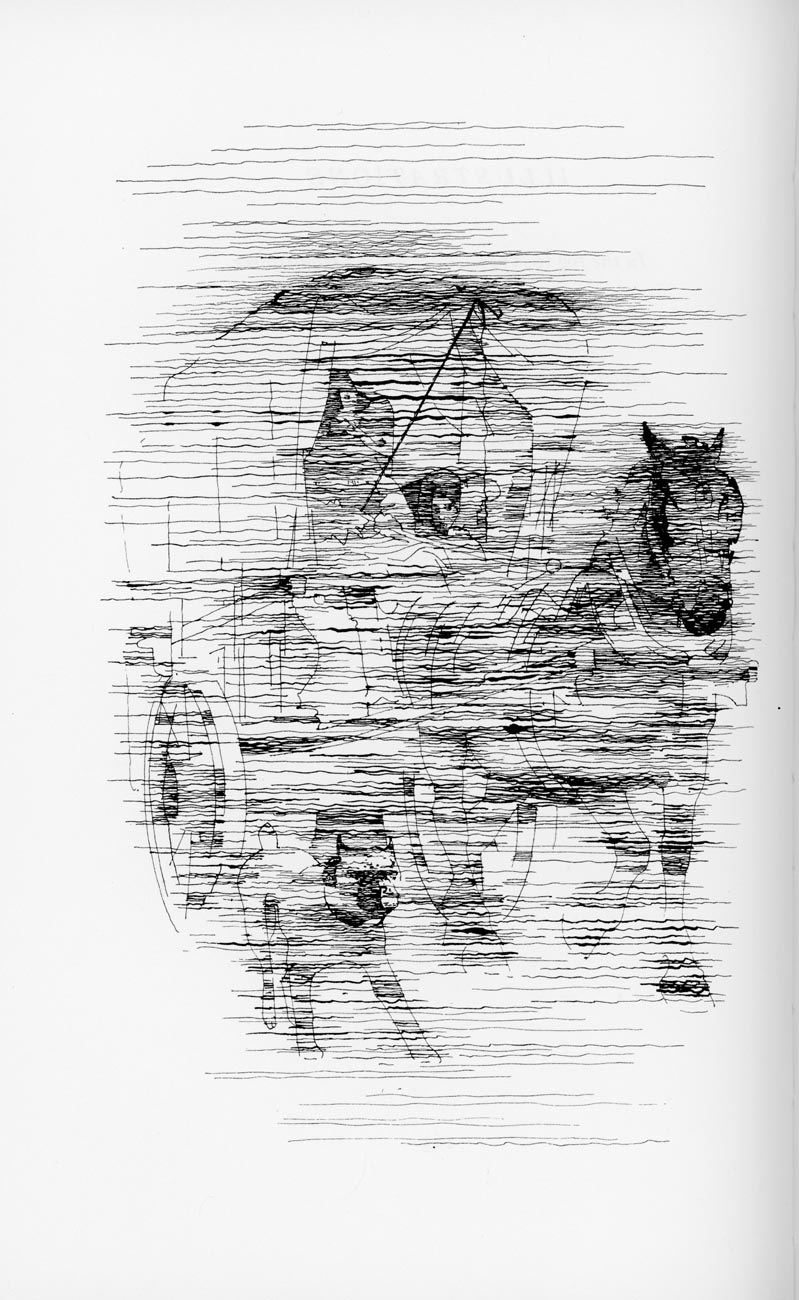

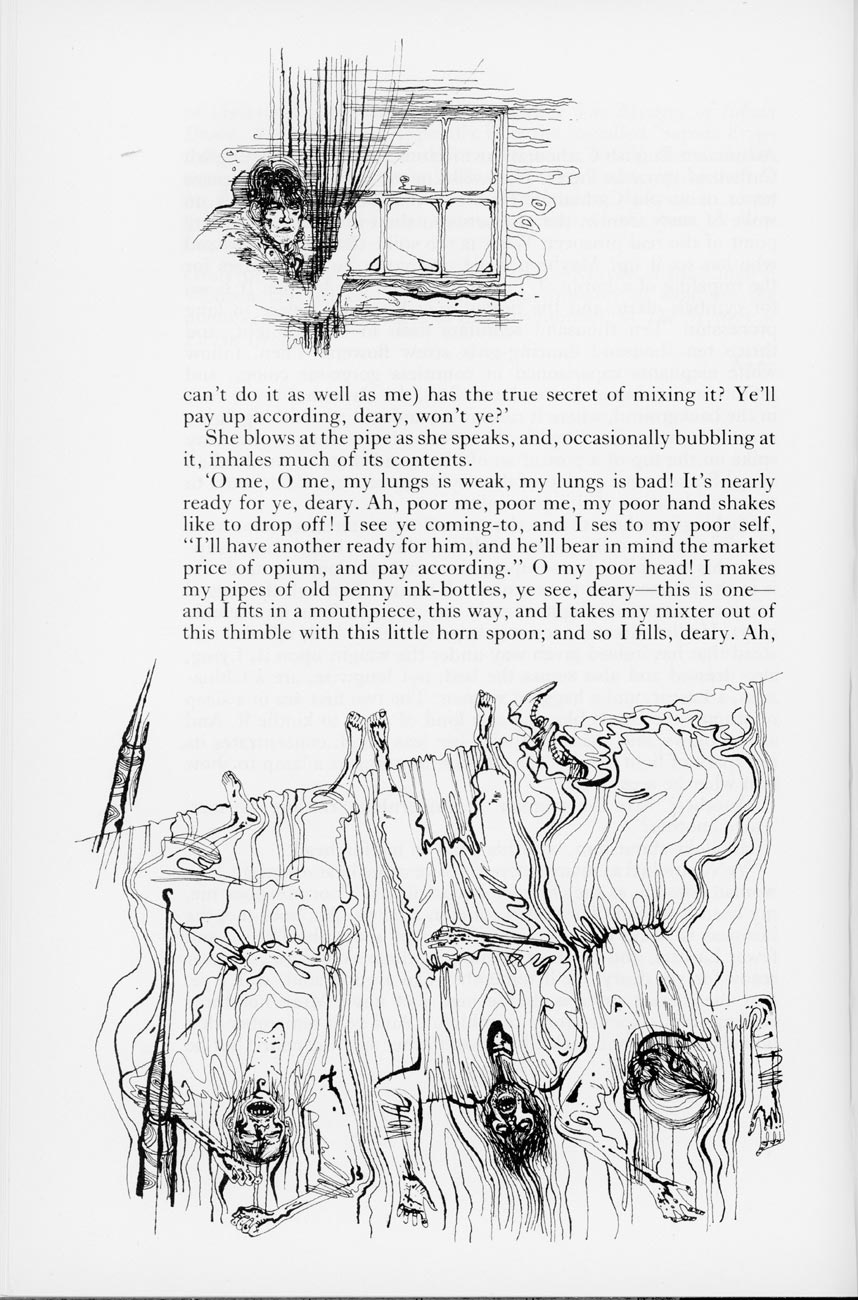

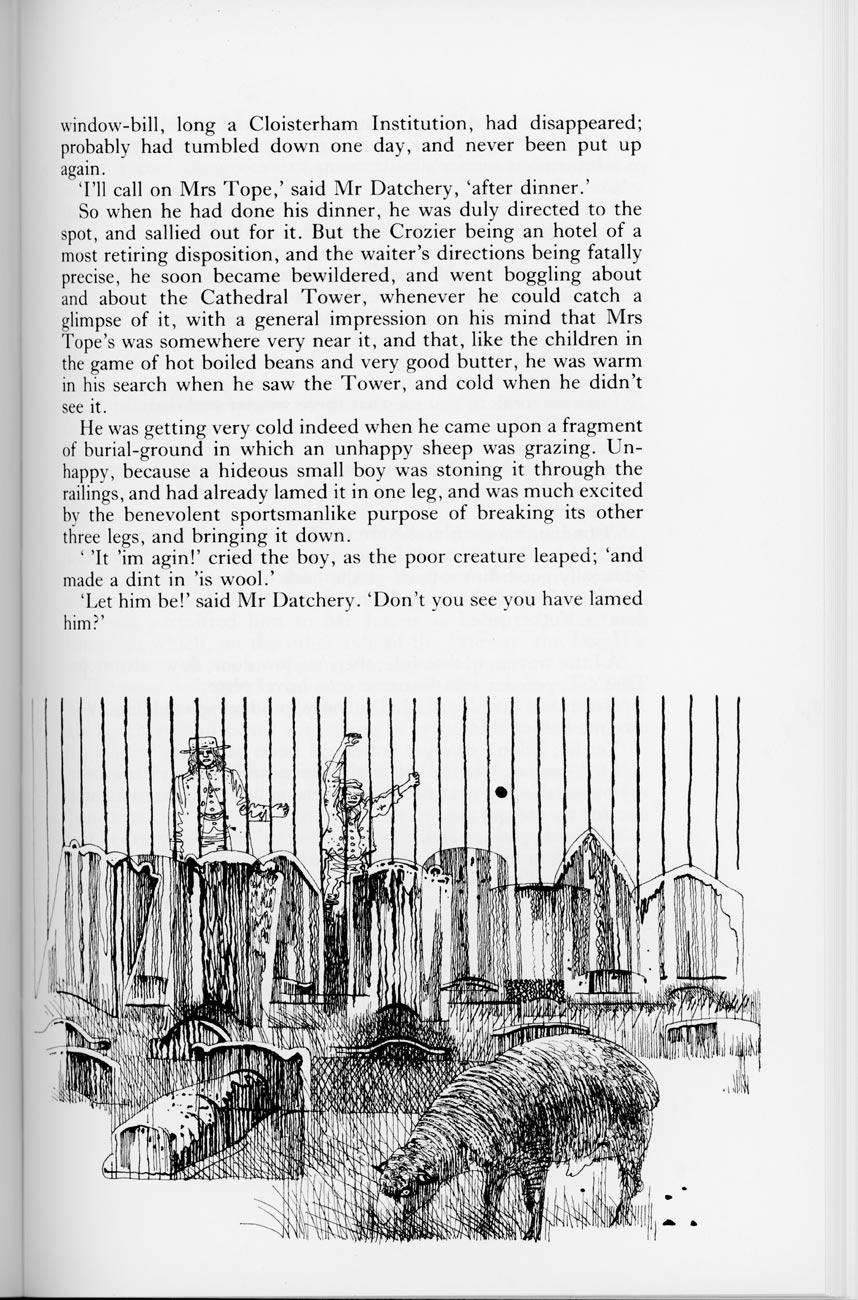

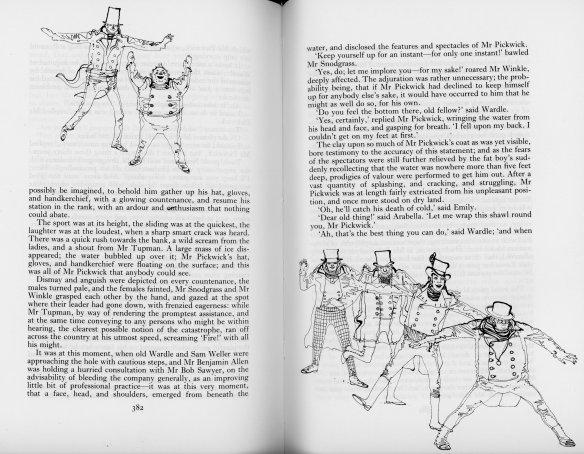

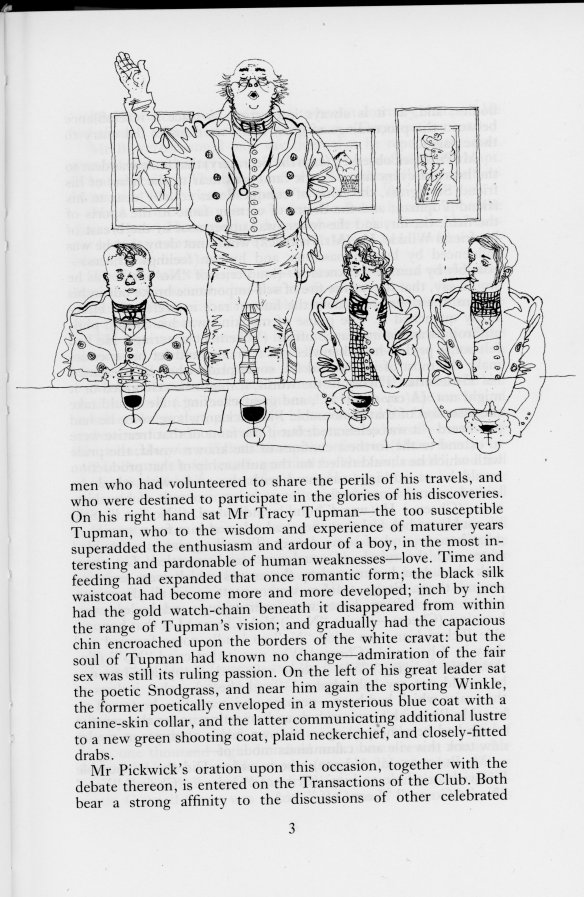

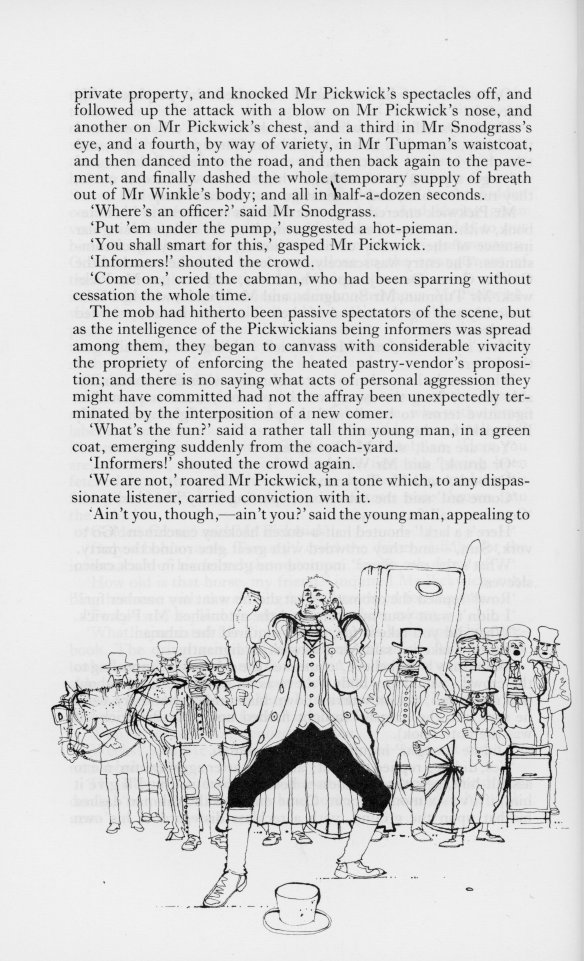

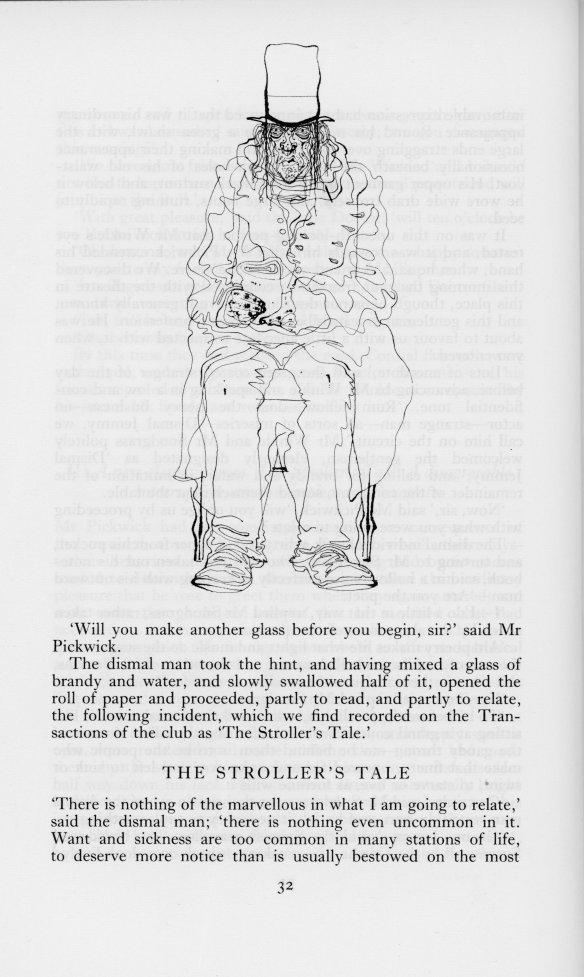

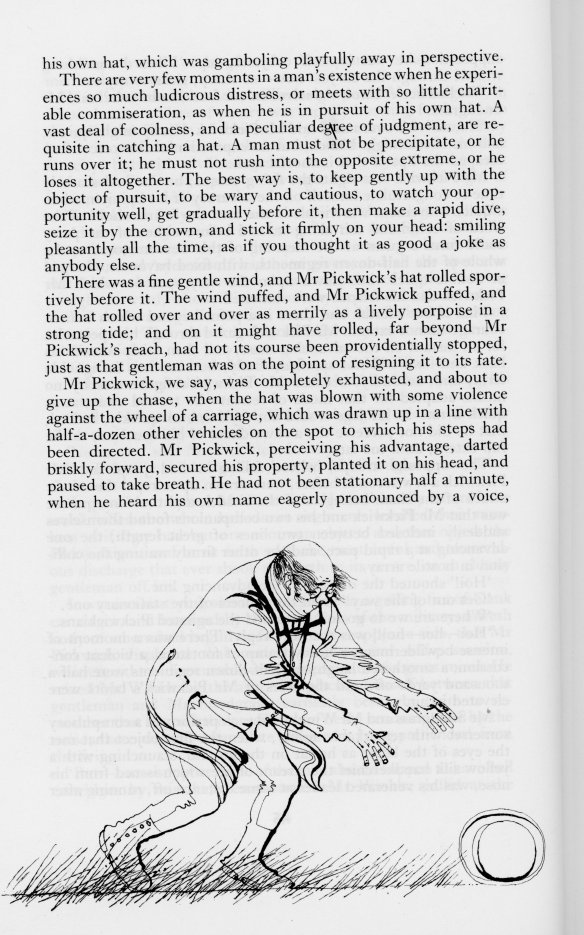

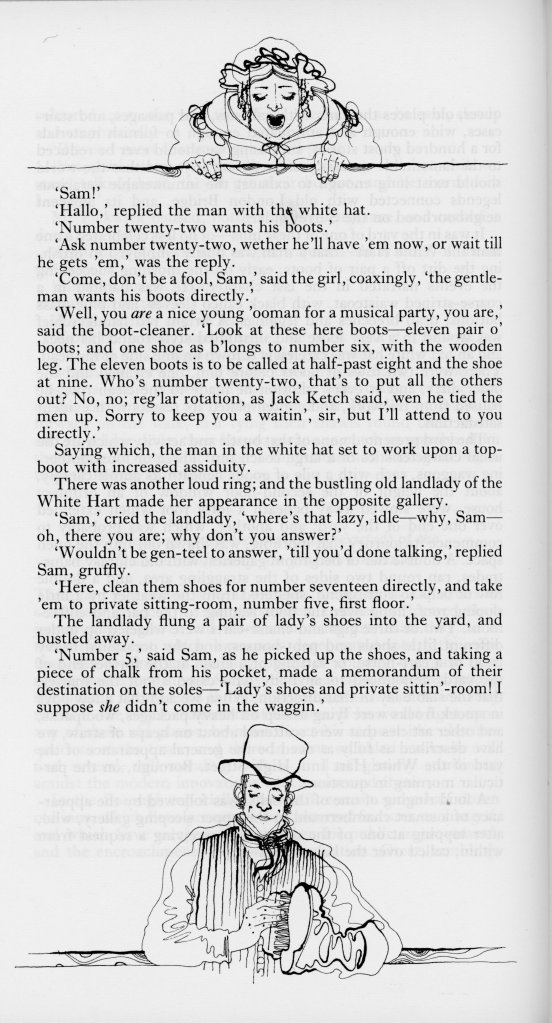

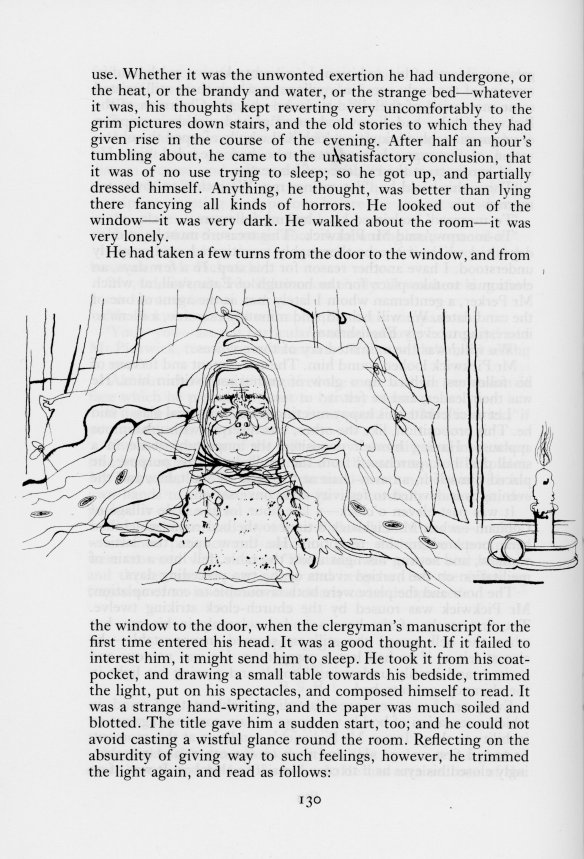

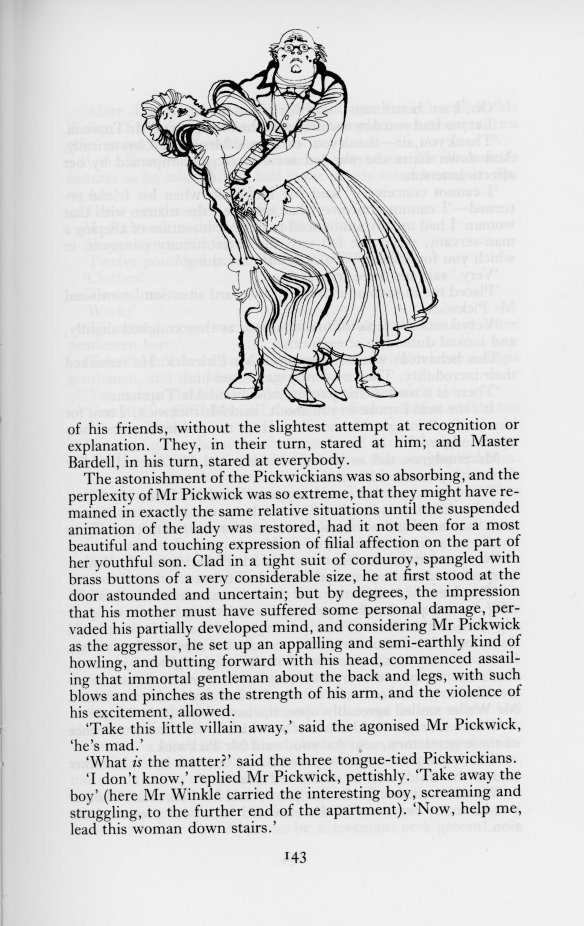

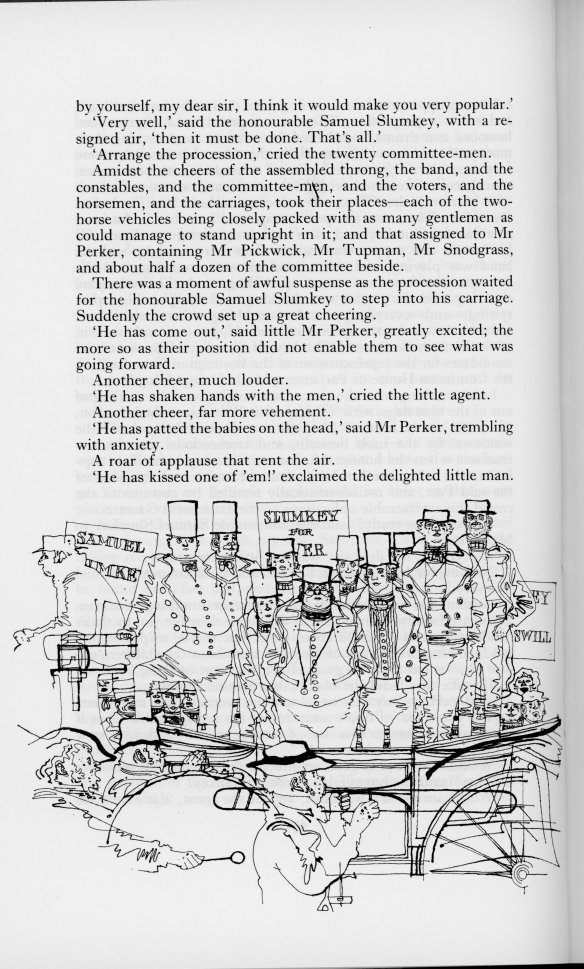

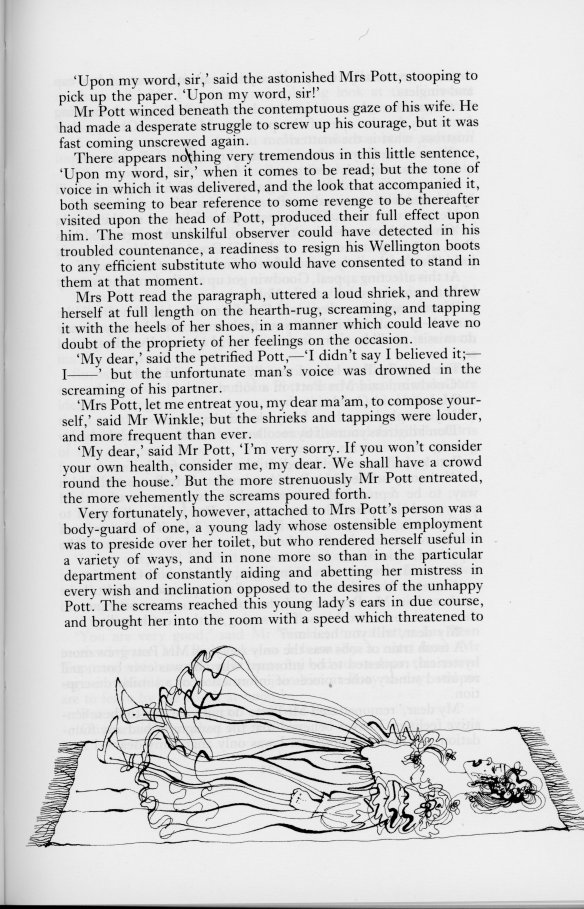

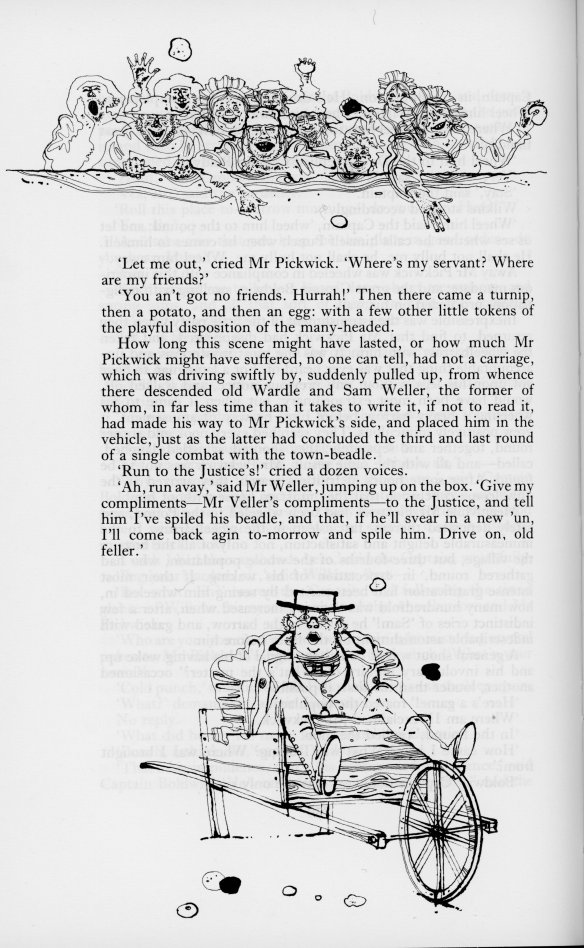

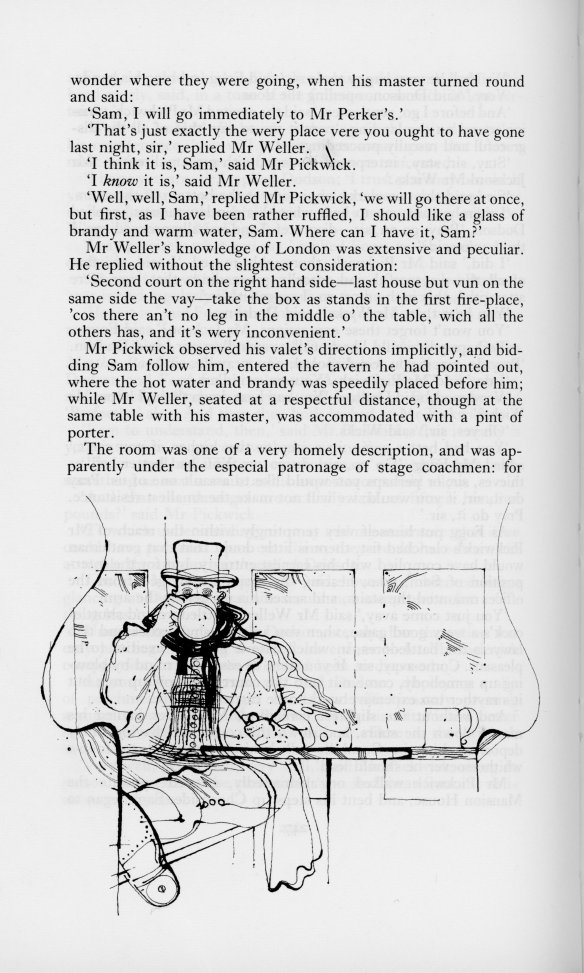

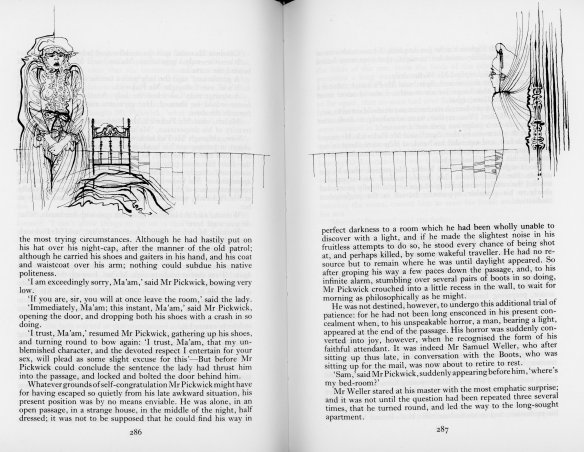

Beginning with the dance,

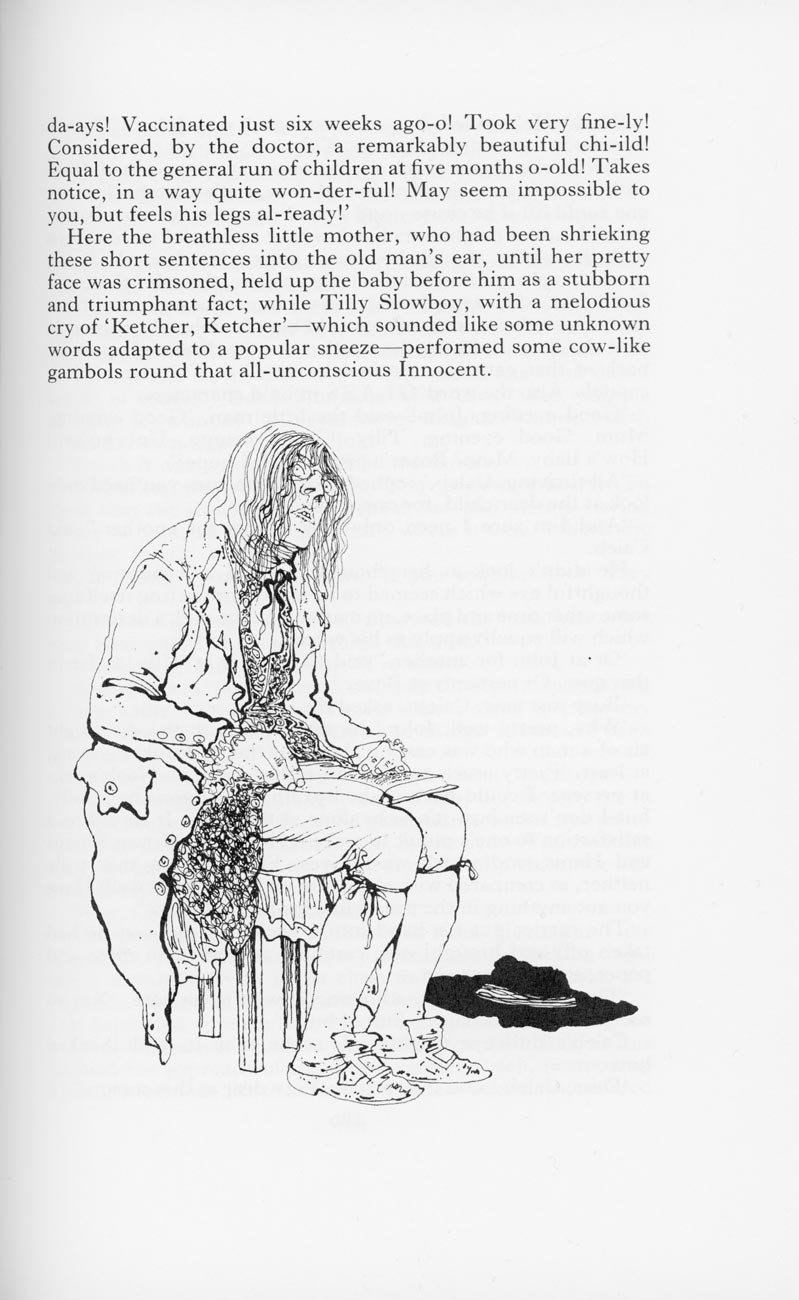

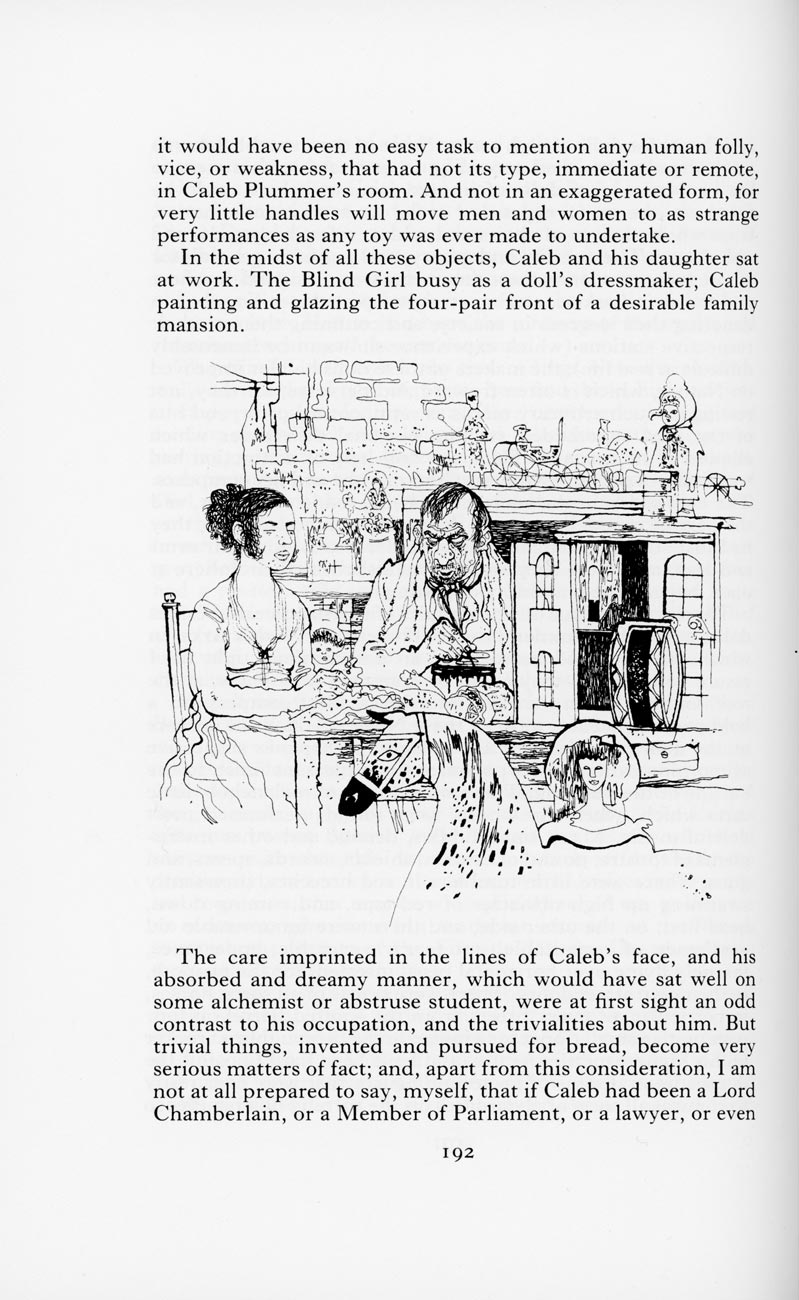

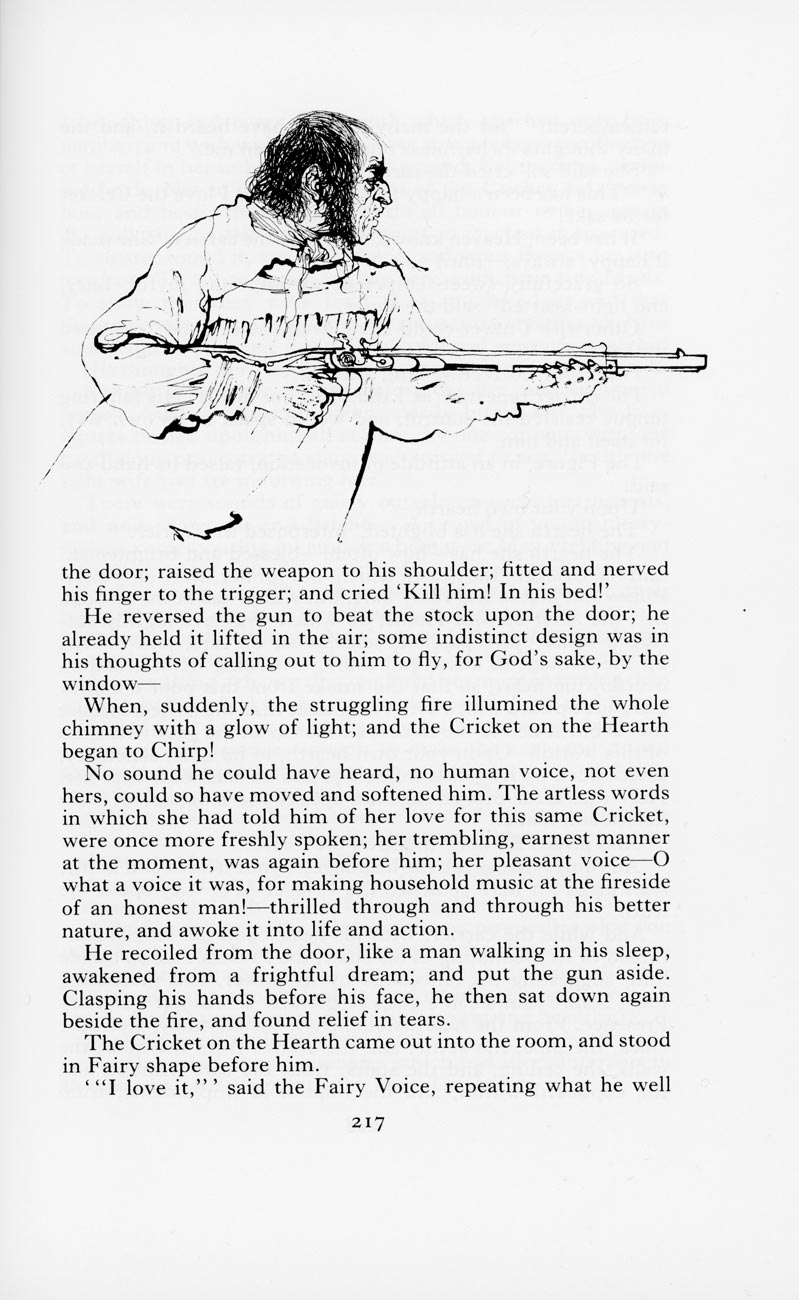

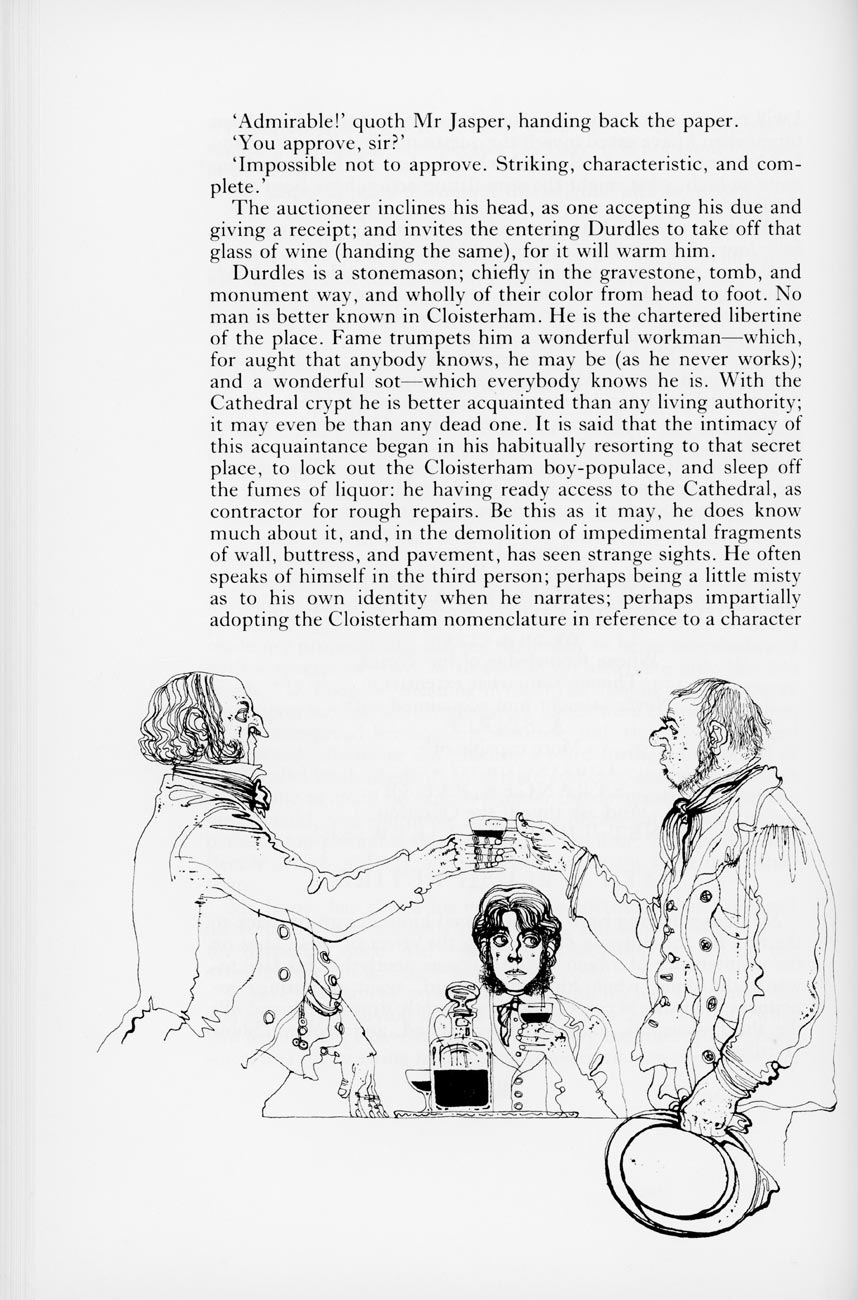

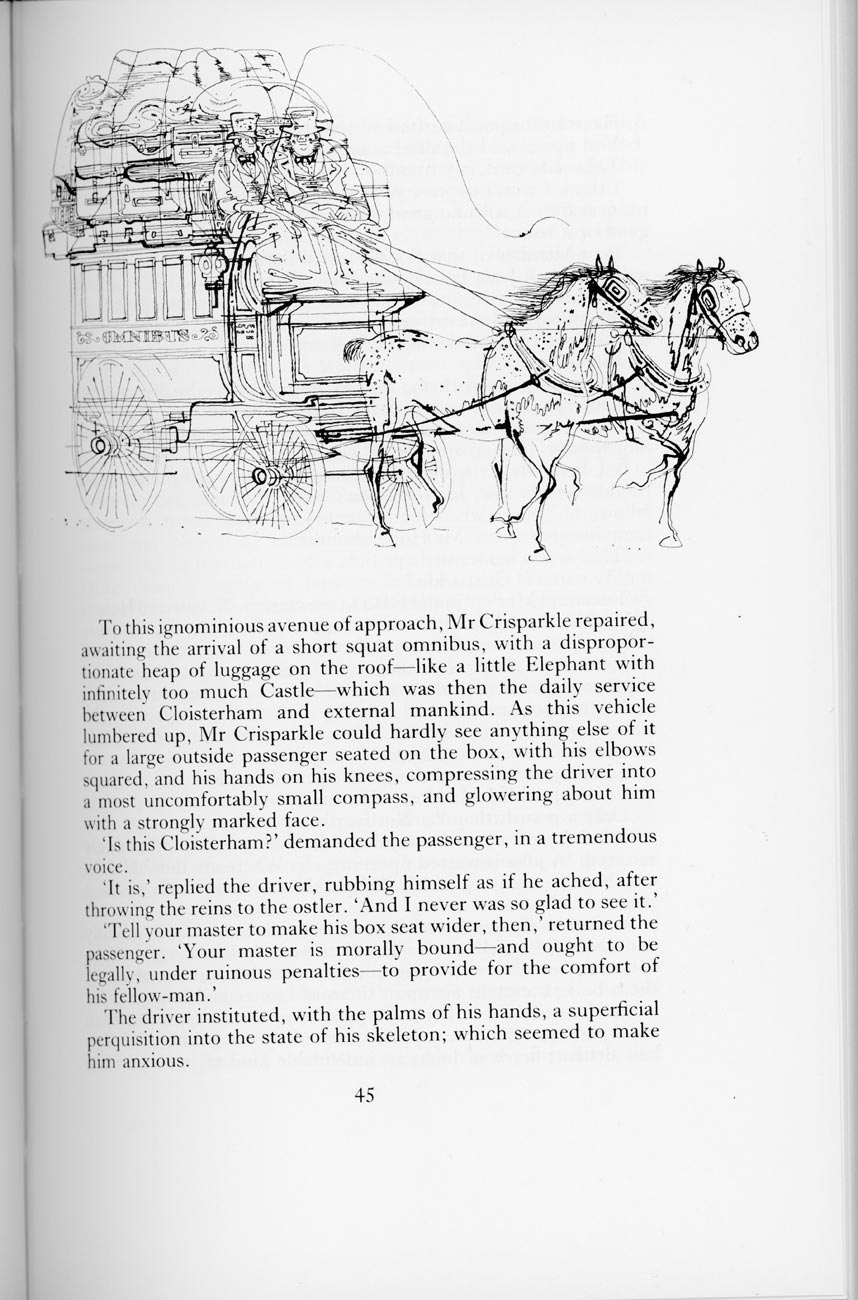

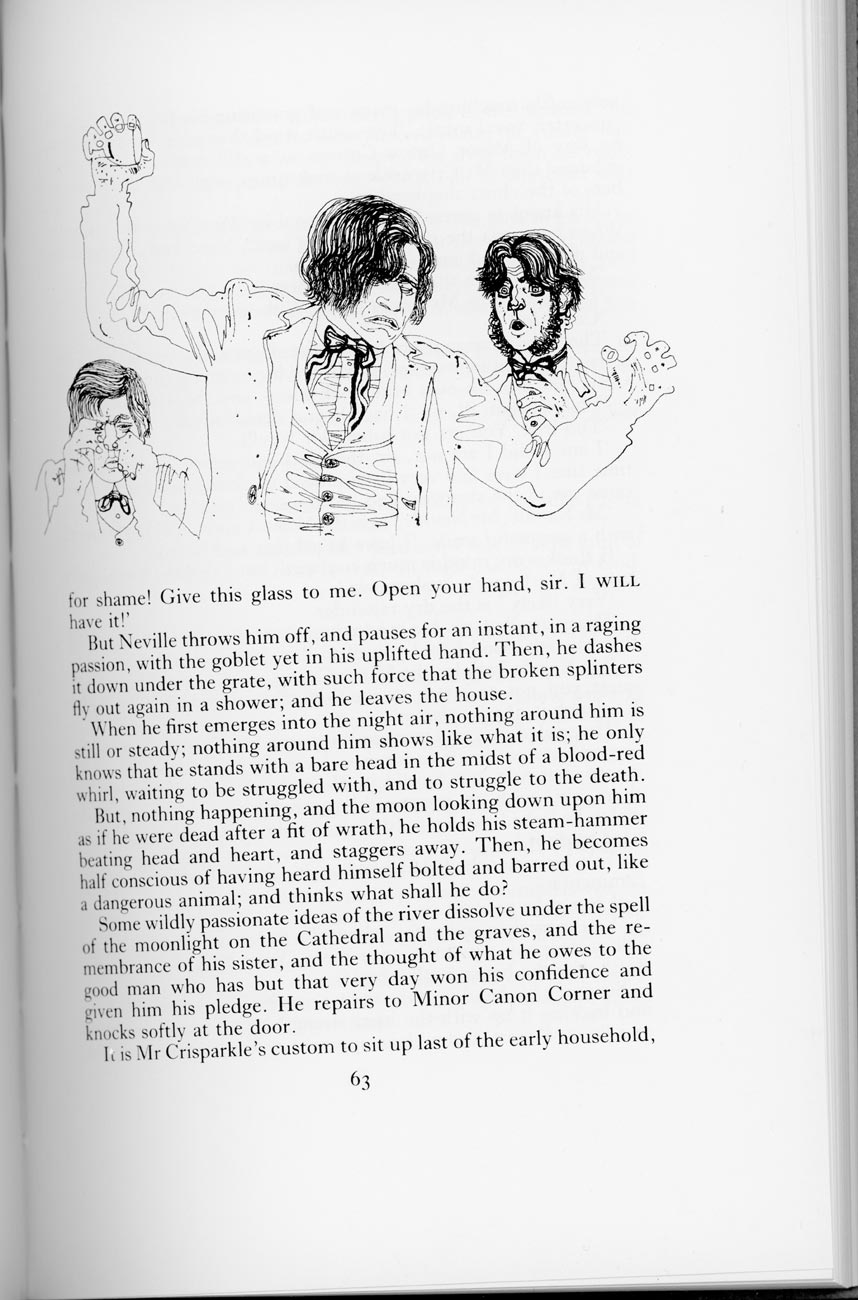

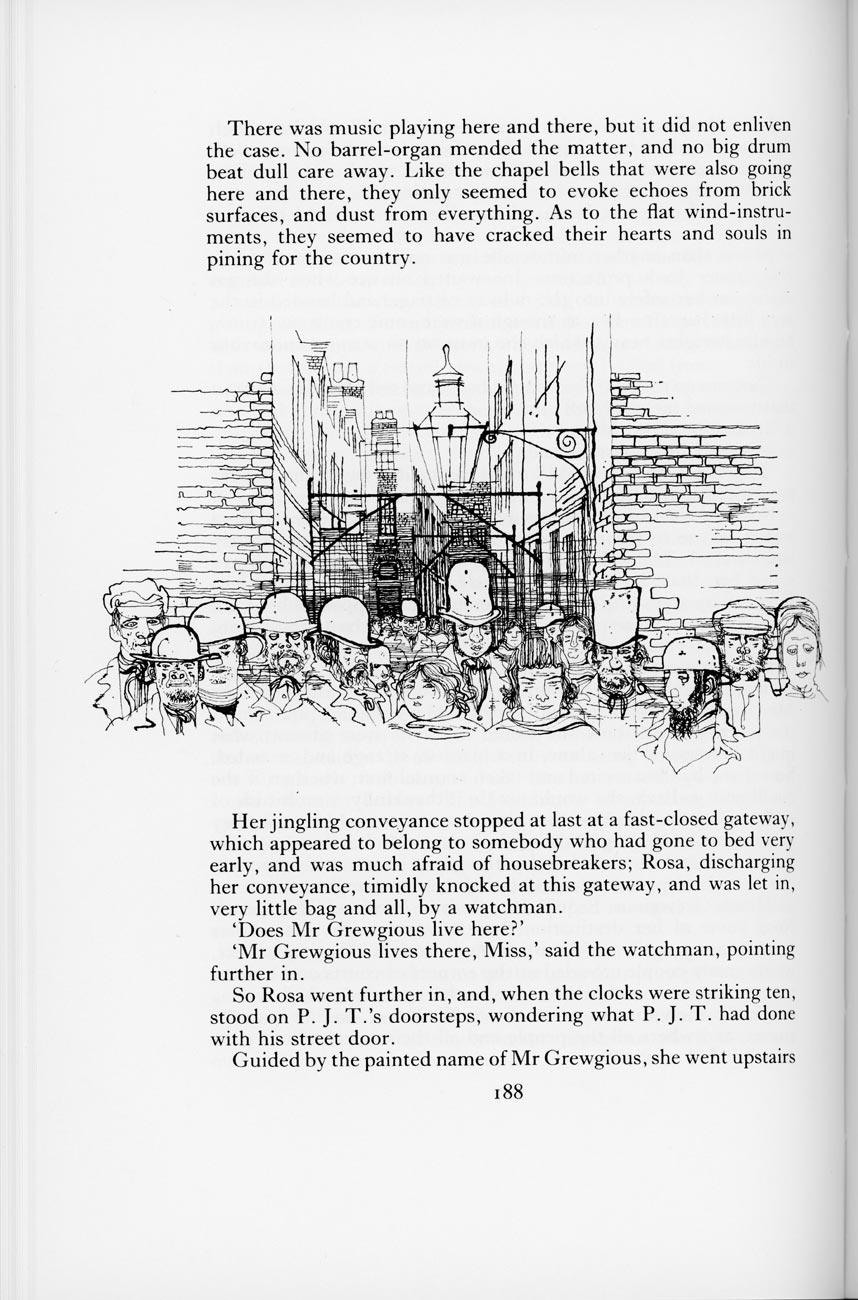

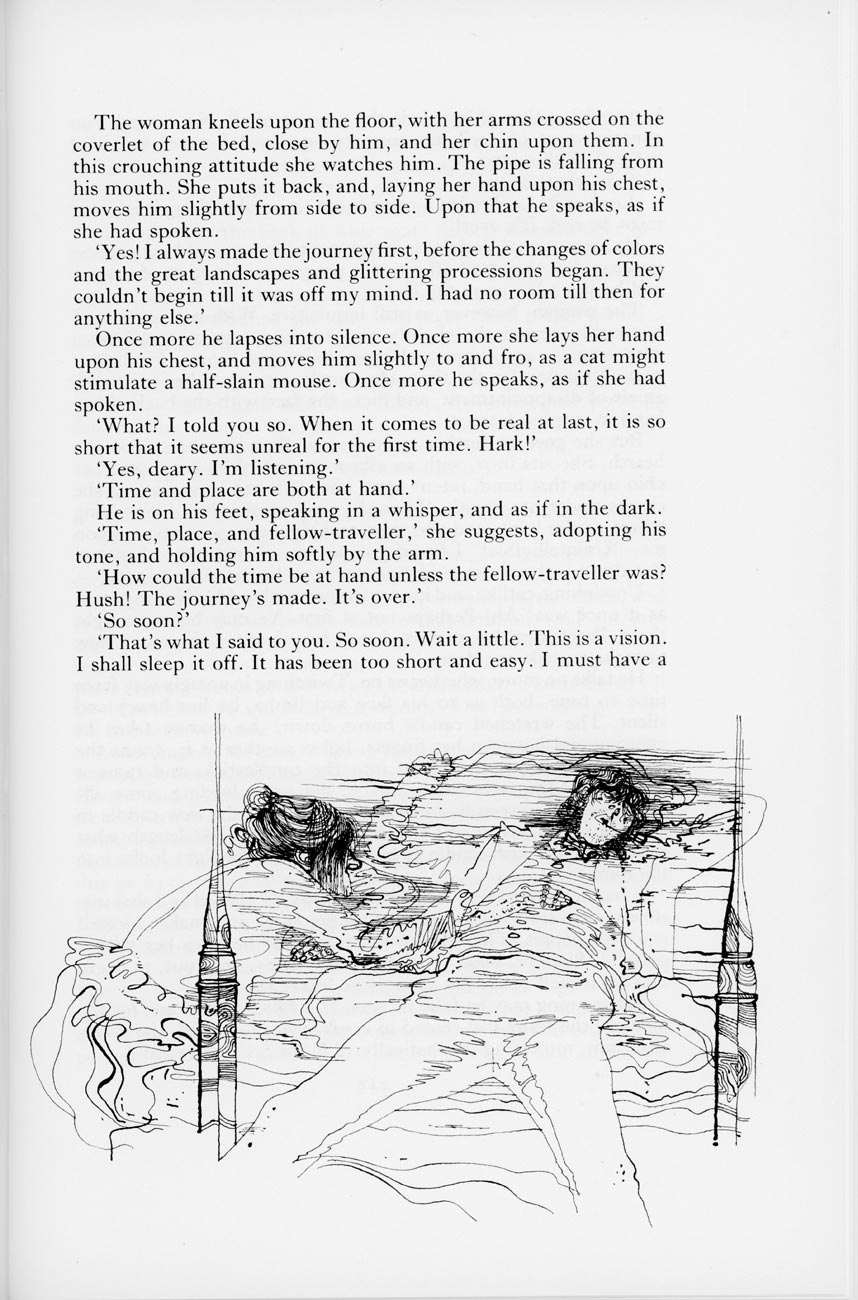

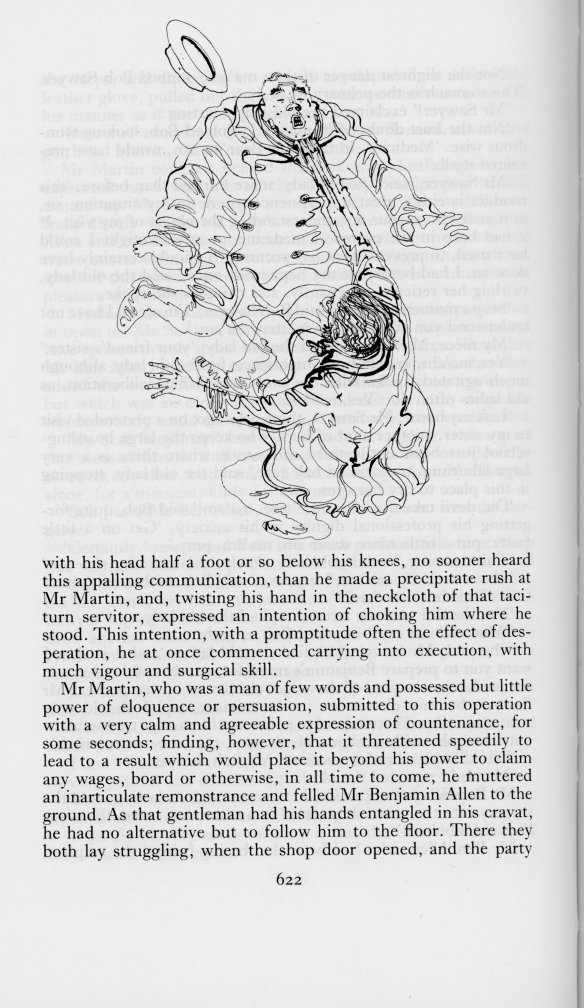

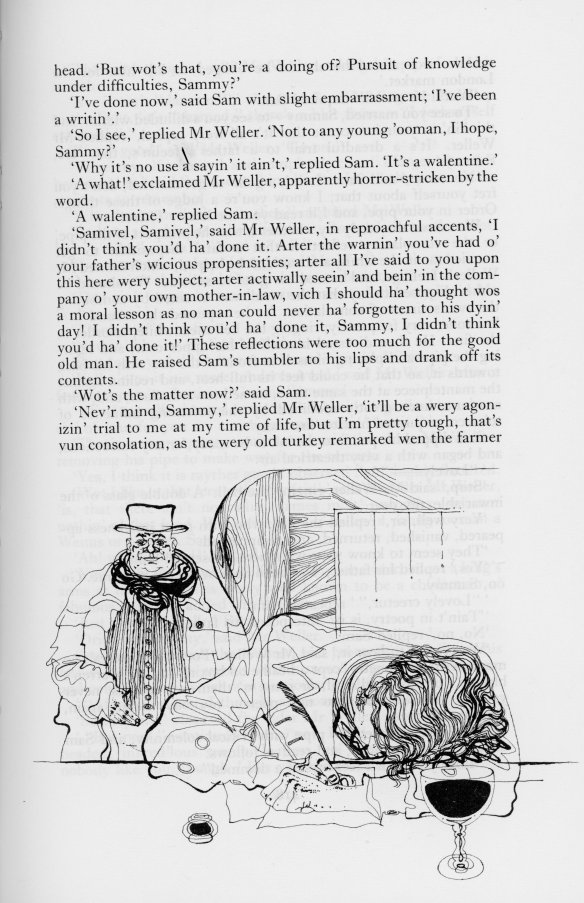

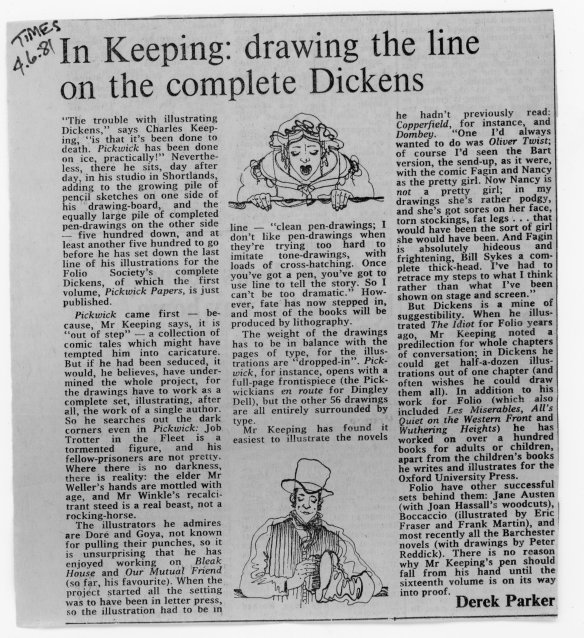

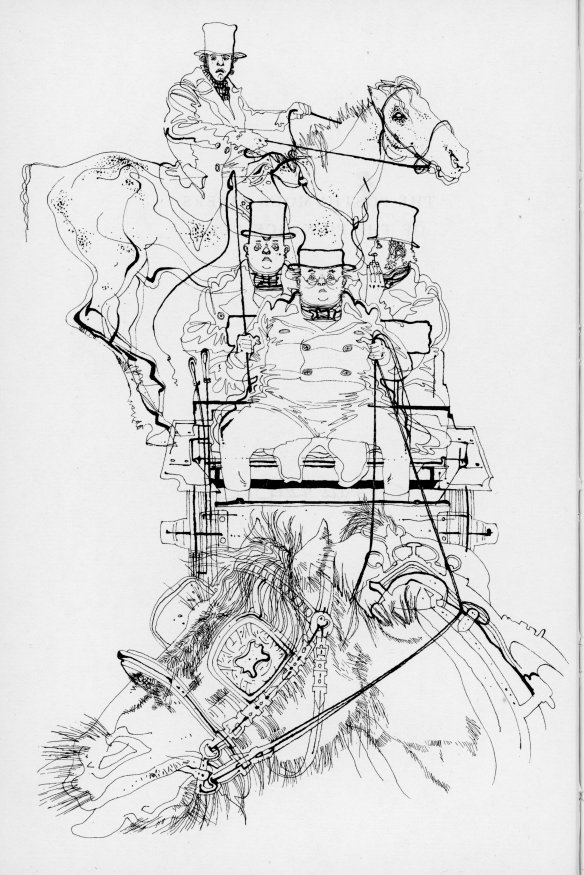

Charles Keeping’s wonderfully moving illustrations are as true as ever to the text.

This evening we dined on Jackie’s well-filled flavoursome beef and onion pie; crisp roast potatoes; crunchy carrots, cauliflower, and firm Brussels sprouts, with tasty, meaty, gravy, with which she drank Hoegaarden and I drank Mendoza Malbec 2019