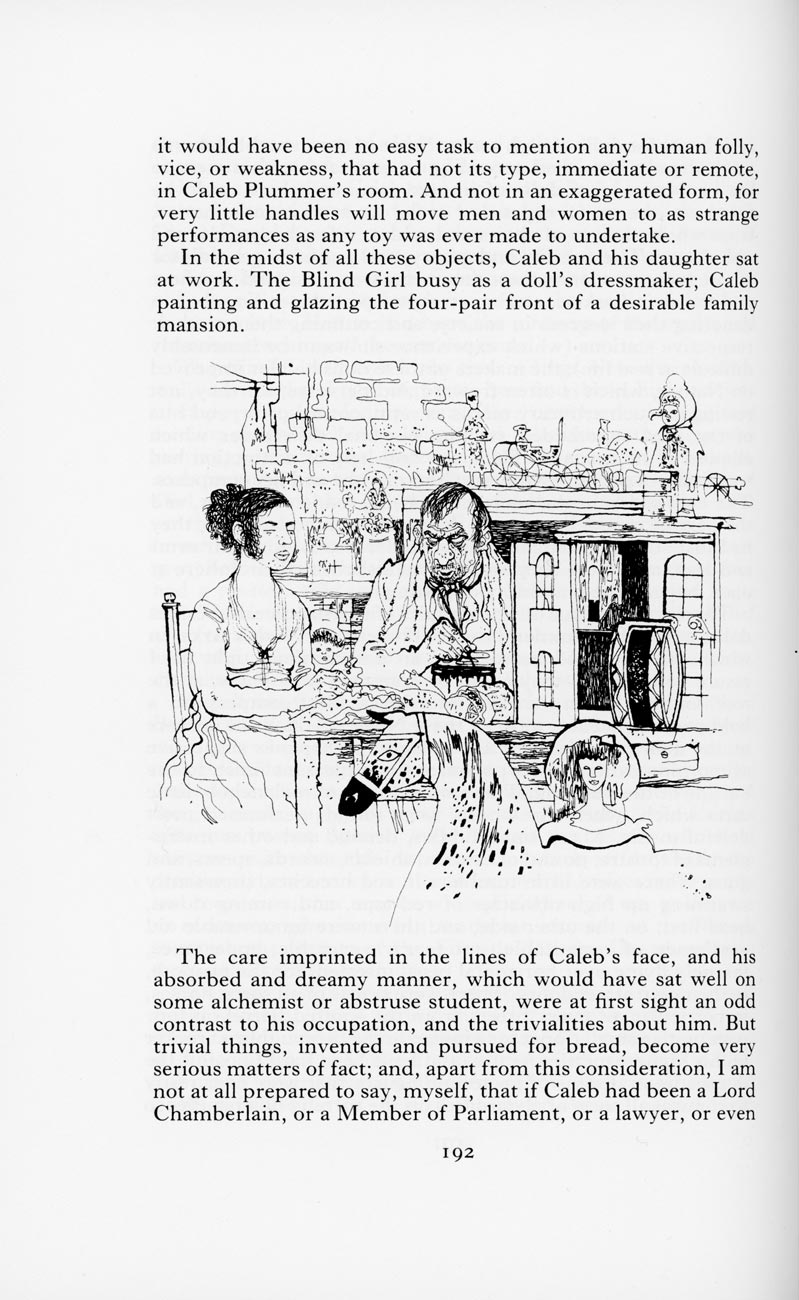

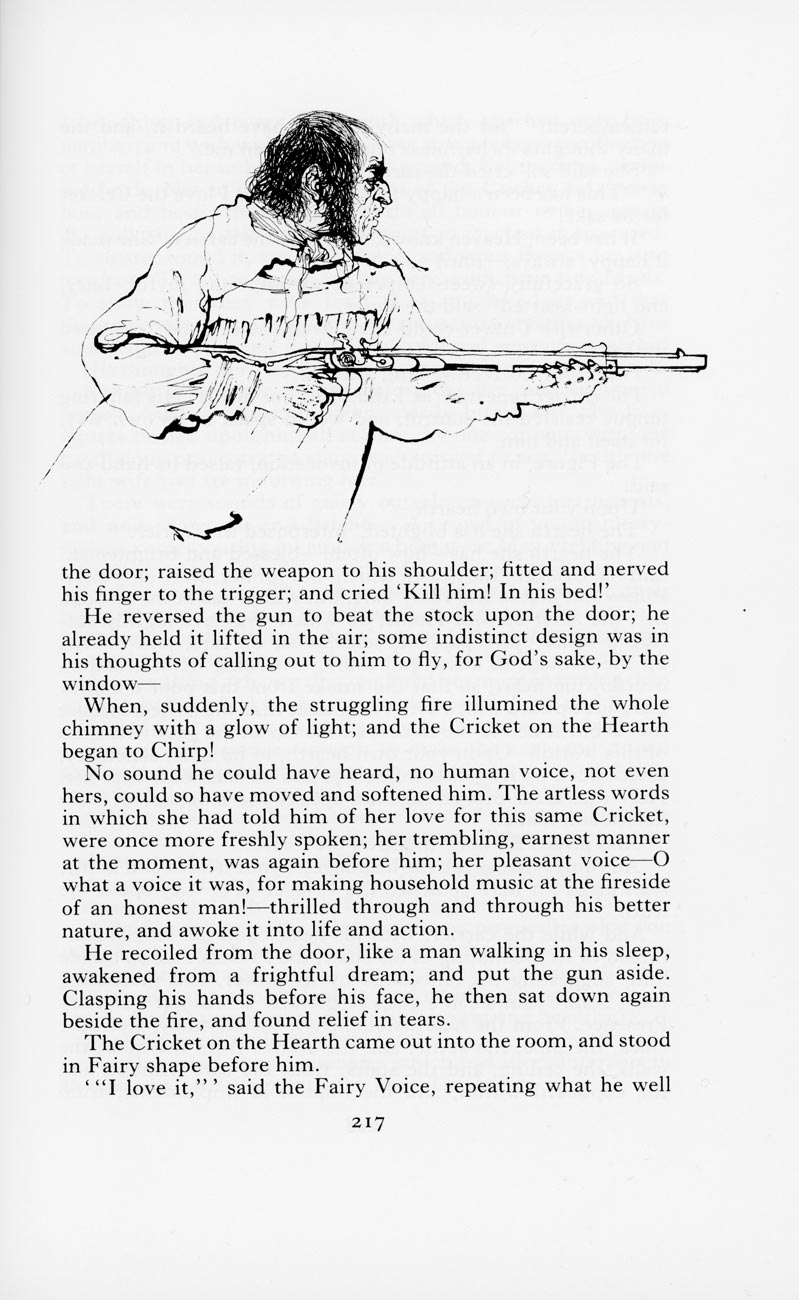

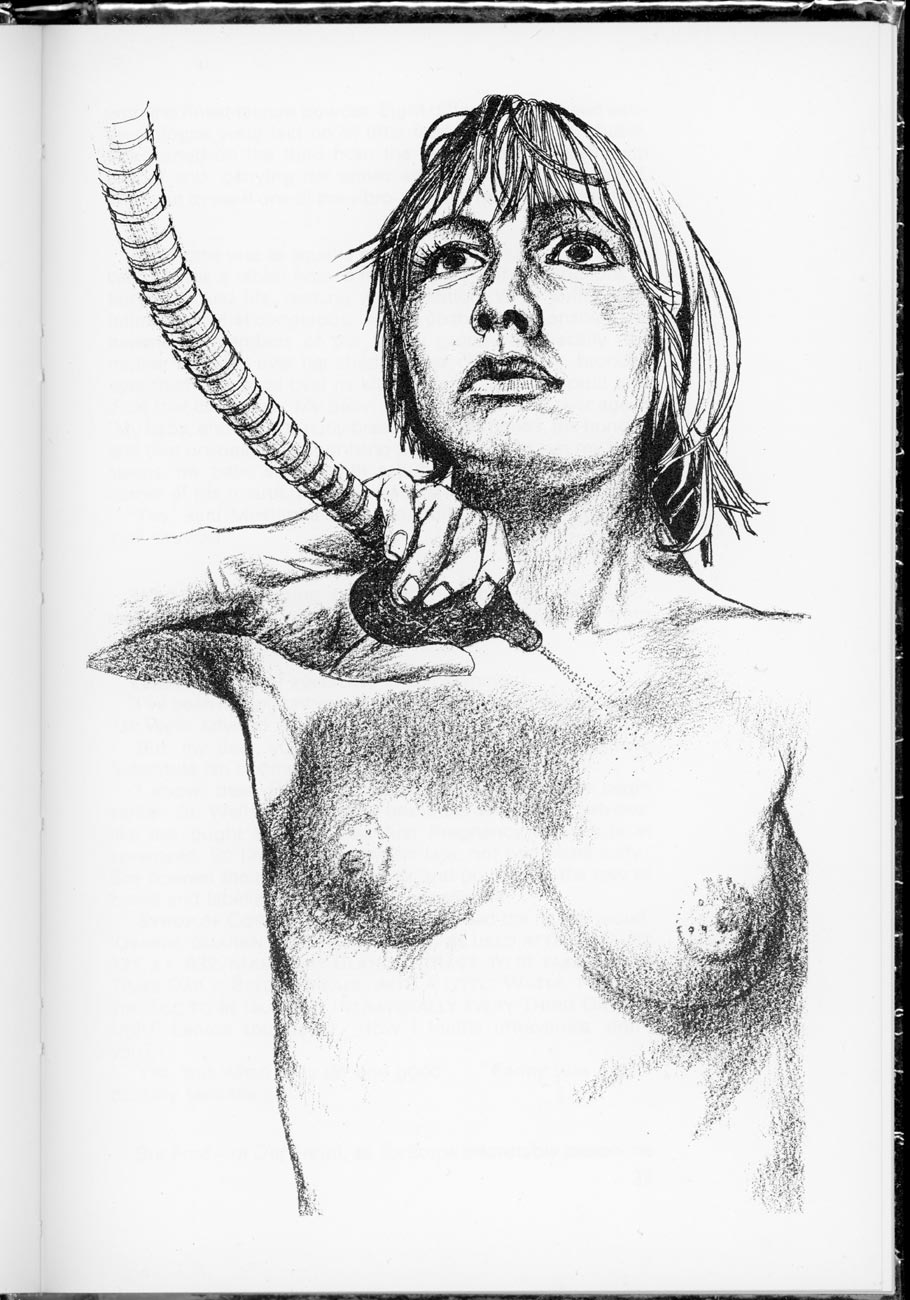

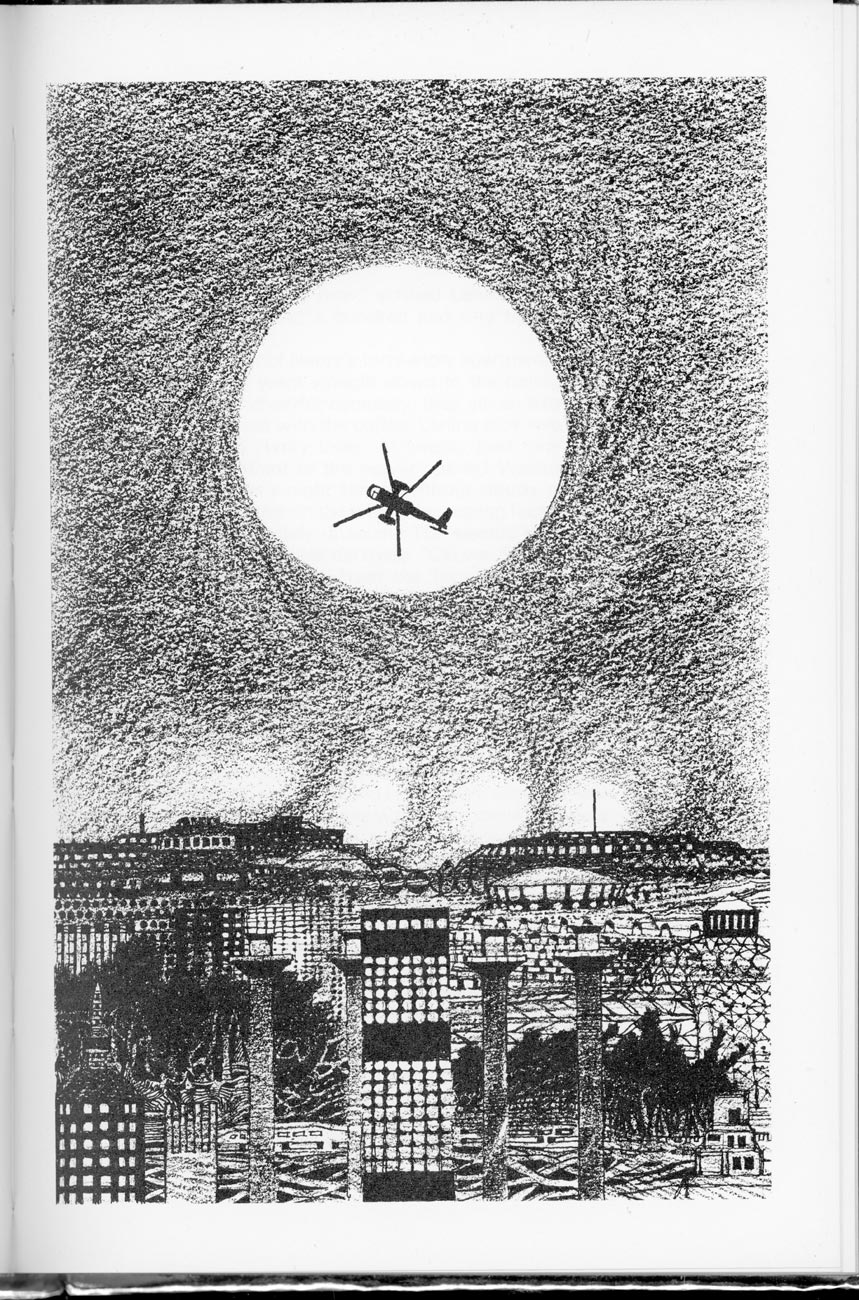

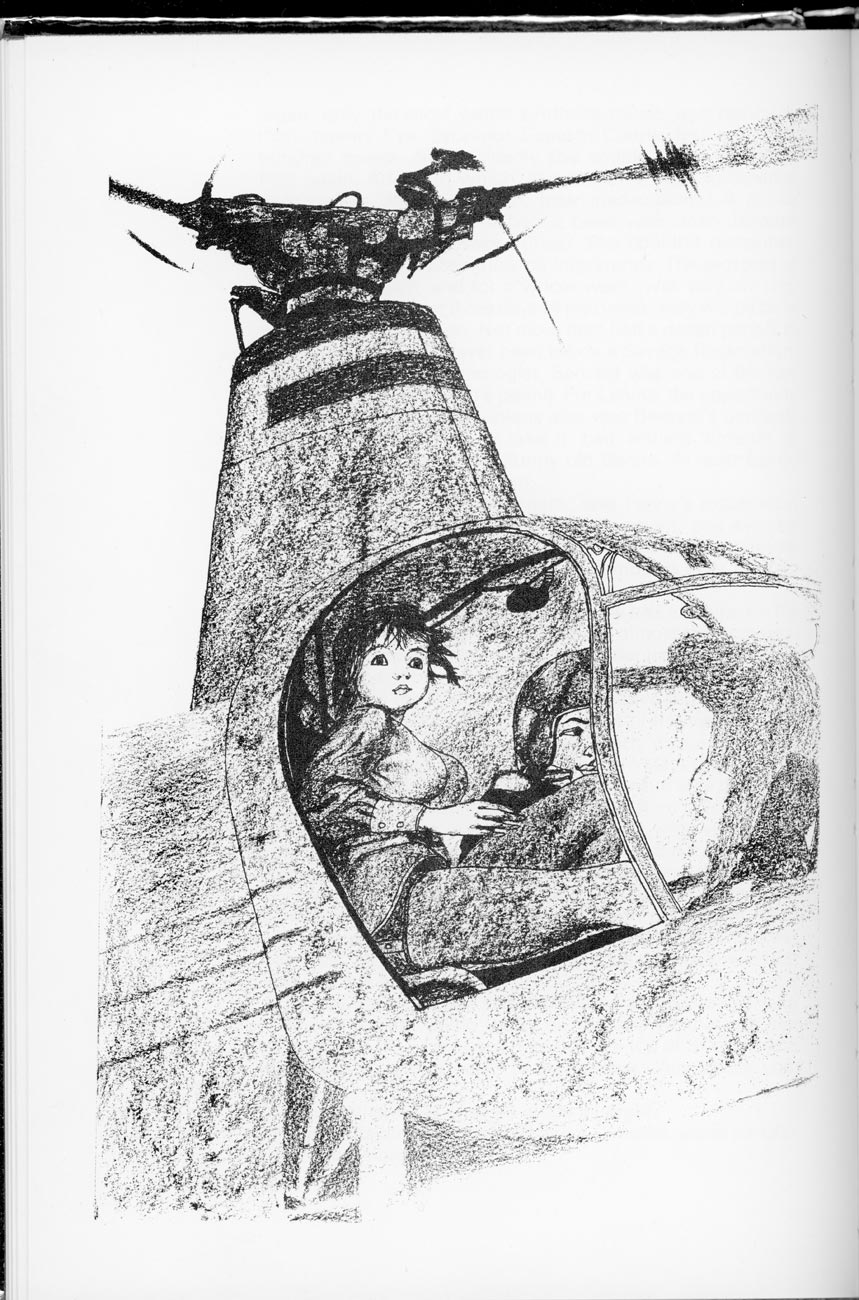

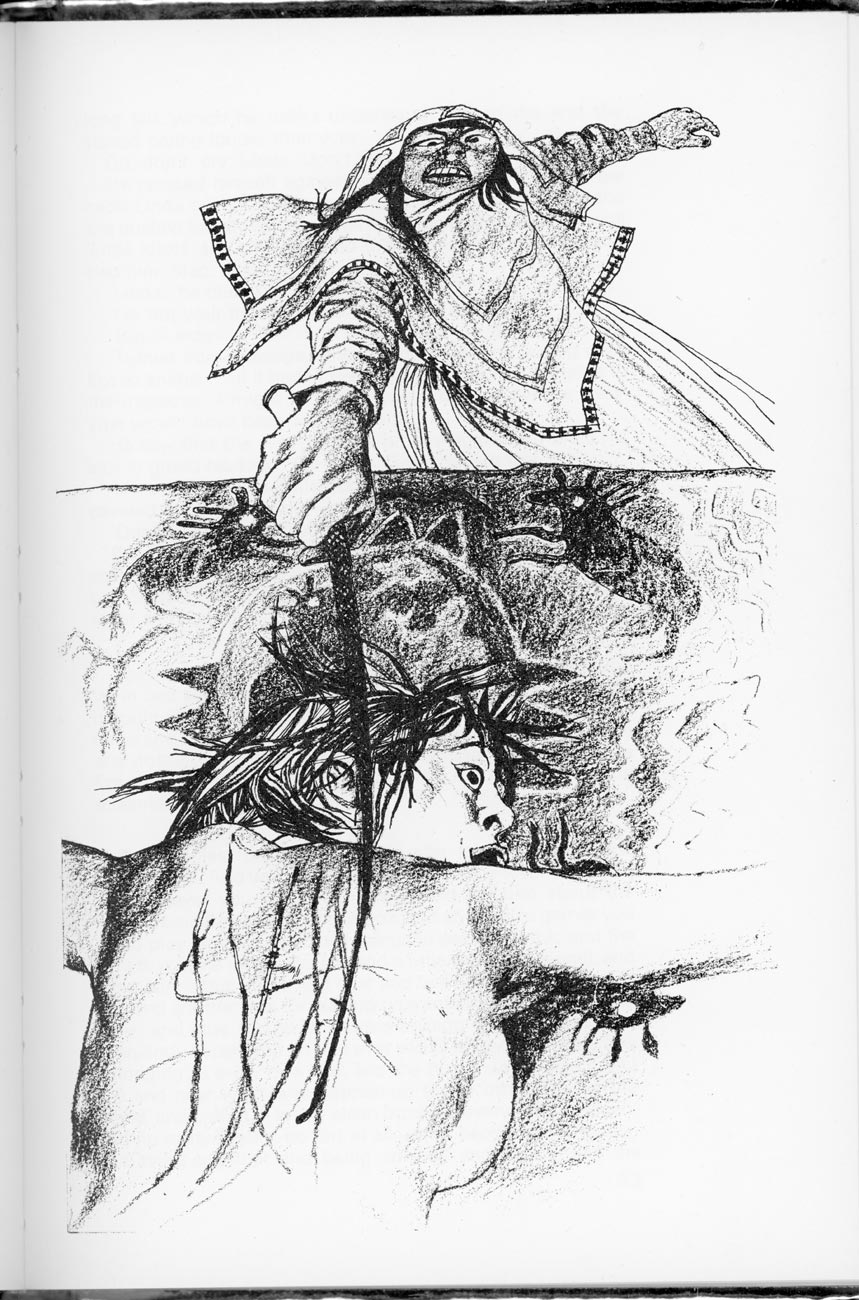

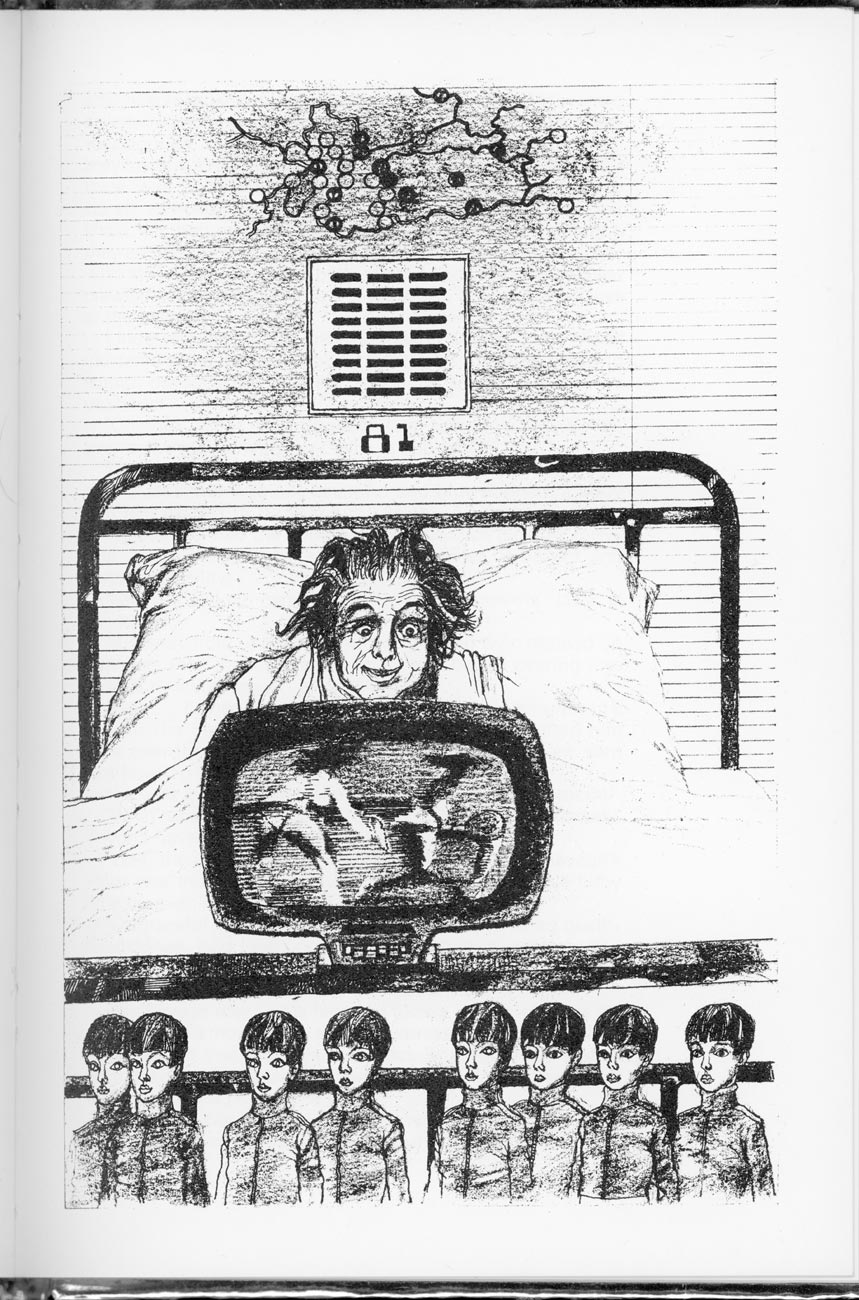

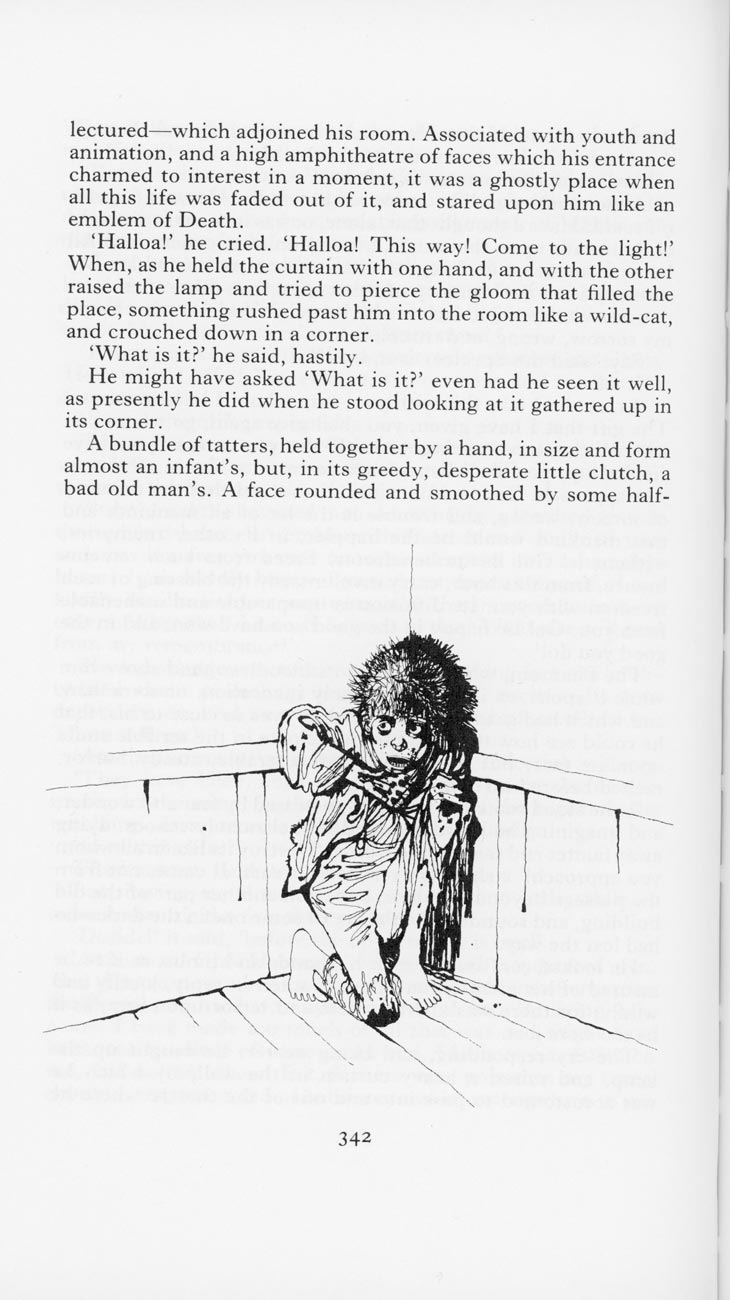

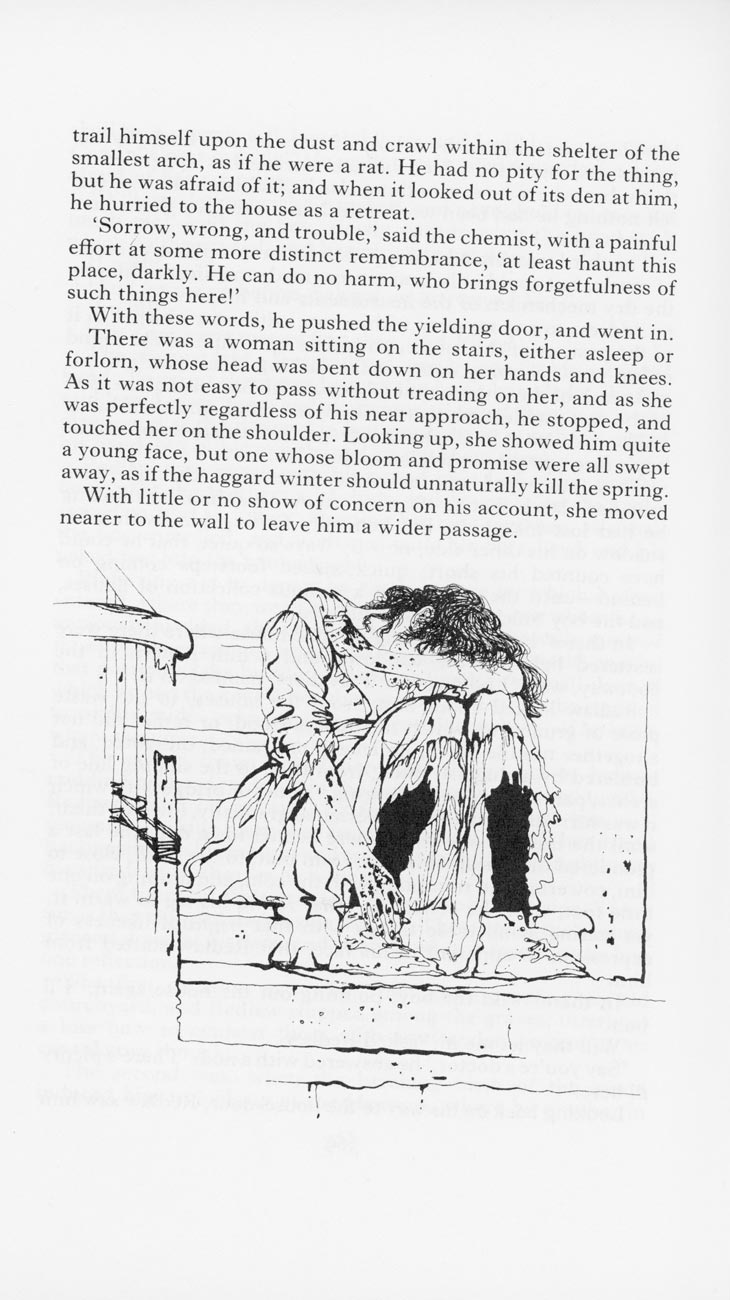

Yesterday I finished reading the fifth and final of Charles Dickens’s Christmas Books. This morning I scanned Charles Keeping’s faithful, first-class, illustrations.

Christopher Hibbert, in his informative introduction to my Folio Society edition, offers the insight that this work reflects painful experiences of the writer’s own life. Seeking freedom from his phantoms ‘The Haunted Man’ of the novella appeals for forgetfulness. The story reveals that forgiveness is really what is required. Once more this tale has been overshadowed by ‘A Christmas Carol’. It does, however contain much of Dickens’s splendid descriptive writing laced with his wry humour.

Highgate West Cemetery, in September 2008, when I produced the batch of colour slides scanned this afternoon, was nowhere near as oppressively gloomy as the heavy atmosphere that prevailed outside my workroom window.

John Turpin, who wrote the text for ‘The Magnificent Seven’, and I needed to join the above paying group to visit this fine example of London’s Victorian landscaped burial grounds. Although wealthy enough to have afforded these final resting places, I have gleaned no information about the various residents.

Steps lead down to these lower levels which also house the columbarium, from the Latin for pigeon-house, which contains niches for storing funeral urns.

I do not know who warranted this elaborate marker.

These three are memorable for their animals. His mastiff guards the remains of Thomas Sayers.

This is what Wikipedia tells us about him: ‘Tom Sayers (15 or 25 May[1] 1826 – 8 November 1865) was an English bare-knuckle prize fighter. There were no formal weight divisions at the time, and although Sayers was only five feet eight inches tall and never weighed much more than 150 pounds, he frequently fought much bigger men. In a career which lasted from 1849 until 1860, he lost only one of sixteen bouts. He was recognized as heavyweight champion of England between 1857, when he defeated William Perry (the “Tipton Slasher”) and his retirement in 1860.

His lasting fame depended exclusively on his final contest, when he faced American champion John Camel Heenan[2] in a battle which was widely considered to be boxing’s first world championship. It ended in chaos when the spectators invaded the ring, and the referee finally declared a draw.

Regarded as a national hero, Sayers, for whom the considerable sum of £3,000 was raised by public subscription, then retired from the ring. After his death five years later at the age of 39, a huge crowd watched his cortège on its journey to London’s Highgate Cemetery.’ His origins are also related in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tom_Sayers

John Atcheler, commemorated by a horse on a plinth, was reputedly horse-slaughterer to Queen Victoria. Maybe someone was indulging a wry sense of humour.

Menageries were popular in Regency and early Victorian England. The lion resting above the remains of George Wombwell represents a favourite exhibit of that individual who, according to Wikipedia

‘was born in Wendon Lofts, Essex in 1777. Around 1800 he moved to London and in 1804 became a shoemaker in Soho. However, when a ship from South America brought two boas to London docks, he bought them for £75 and began to exhibit them in taverns. He soon made a good profit.

Wombwell began to buy exotic animals from ships that came from Africa, Australia and South America, and collected a whole menagerie and put them on display in Soho. In 1810 he founded the Wombwell’s Travelling Menagerie and began to tour the fairs of Britain. By 1839 it totalled fifteen wagons, and was accompanied by a brass band.

His travelling menagerie included elephants, giraffes, a gorilla, a hyena, kangaroo, leopards, 6 lions, llamas, monkeys, ocelots, onagers, ostriches, panthers, a rhino (“the real unicorn of scripture”), 3 tigers, wildcats and zebras. However, because many of the animals were from hotter climes, many of them died in the British climate. Sometimes Wombwell could profitably sell the body to a taxidermist or a medical school, other times he chose to exhibit the dead animal as a curiosity.

Wombwell bred and raised many animals himself, including the first lion to be bred in captivity in Britain; he named it William in honour of William Wallace. In 1825 Warwick, Wombwell, in collaboration with Sam Wedgbury and dog dealer Ben White’s assistant Bill George,[1]arranged a Lion-baiting between his docile lion Nero and six bulldogs. Nero refused to fight but when Wombwell released Wiliam, he mauled the dogs and the fight was soon stopped.

Over the years, Wombwell expanded three menageries that traveled around the country. Wombwell was a regular exhibitor at the annual Knott Mill Fair in Manchester, a venue he sometimes shared with Pablo Fanque‘s circus.[2][3] He was invited to the royal court on five occasions to exhibit his animals, three times before Queen Victoria. In 1847 the Queen Victoria noted the bravery of the “British Lion Queen”, the nickname of Ellen Chapmanwho appeared with lions, leopards and tigers. Chapman married Wombwell’s business rival George Sanger in 1850.[4]

On one occasion Prince Albert summoned him to look at his dogs who kept dying and Wombwell quickly noticed that their water was poisoning them. When the prince asked what he could do in return for this favour, Wombwell said, “What can you give a man who has everything?” However, Wombwell requested some oak timber from the recently salvaged Royal George. From this he had a coffin fashioned for himself, which he then proceeded to exhibit for a special fee.

Wombwell frequented Bartholomew Fair in London and even developed a rivalry with another exhibitor, Atkins. Once when he arrived at the fair, his elephant died and Atkins put up a sign “The Only Live Elephant in the Fair”. Wombwell simply put up a scroll with the words “The Only Dead Elephant in the Fair” and explained that seeing a dead elephant was an even a rarer thing than a live one. The public, realising that they could see a living elephant at any time, flocked to see and poke the dead one. Throughout the fair Atkins’ menagerie was largely deserted, much to his disgust.

George Wombwell died in 1850 and was buried in his Royal George coffin in Highgate Cemetery, under a statue of his lion Nero.

The book George Wombwell (1777 – 1850): Volume One recalls the lion and dog fight in Warwick with well researched evidence, but questions whether it ever actually took place. George Wombwell (1777 – 1850): Volume Two covers Wombwell’s life as the most famous showman, from his arrival in London around 1800 to his death in 1850.[5]

In 1851 a tapir broke out of its den at Wombwell’s Menagerie in Rochdale, causing panic among the spectators.[6]

The cedar of Lebanon in the second and third of these pictures is one of the cemetery’s original plantings.

This evening we dined on Jackie’s substantial, wholesome, chicken and vegetable stoup and crusty bread with which she drank Hoegaarden and I drank more of the Fleurie.